Witchcraft claims linked to 17th Century women's jobs - Cambridge historian

- Published

In the mid-17th Century, hundreds of women were executed for the crime of witchcraft

Employment types open to 17th Century women came with a much higher risk of magical sabotage claims, a Cambridge University historian has found.

Dr Philippa Carter used the casebooks, external of a Buckinghamshire astrologer-doctor to analyse links between witchcraft accusations and women's occupations.

These included healthcare, childcare, dairy production or livestock care.

Women were "the first line of defence" against death or disease, risking witchcraft claims, said Dr Carter.

Dr Philippa Carter's research has shown a link between the work available to them and accusations of magical sabotage

In contrast to men's work, which often involved labour with sturdy or rot-resistant materials such as iron, fire or stone, women worked in areas where decay was more likely.

Dr Carter, from the department of history and philosophy of science, said: "Natural processes of decay were viewed as 'corruption'. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese."

This meant they were much more likely to be linked to death, disease or spoilage, causing their clients suffering or financial loss.

But in addition, women often worked several jobs to make ends meet, crisscrossing between homes, bakehouses, wells and marketplaces, rather than in fields or workshops.

"They worked not just in one high-risk sector, but in many at once. It stacked the odds against them," said Dr Carter.

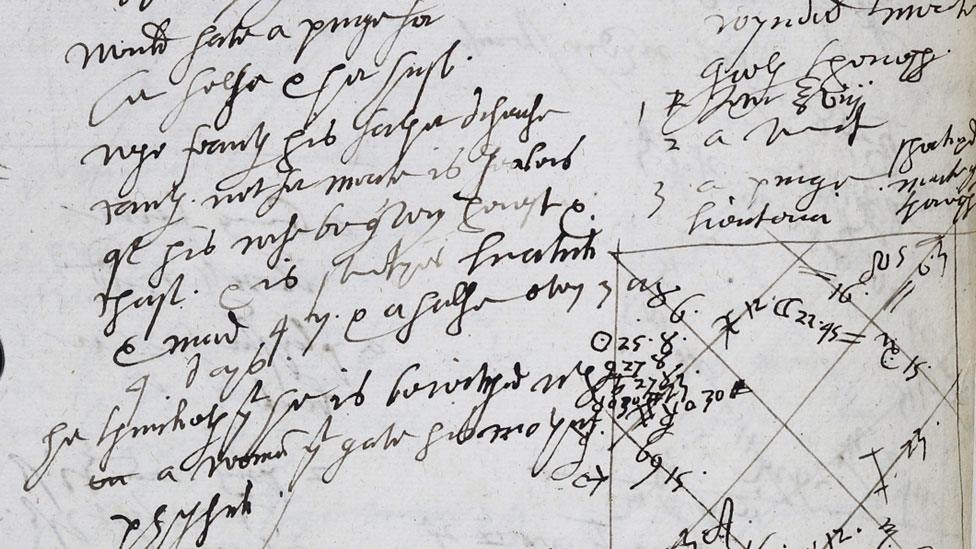

In this page from the casebook, Mrs Peddar, 33, of Potters Perry says her husband believes he was bewitched by a woman who gave his mother medicine

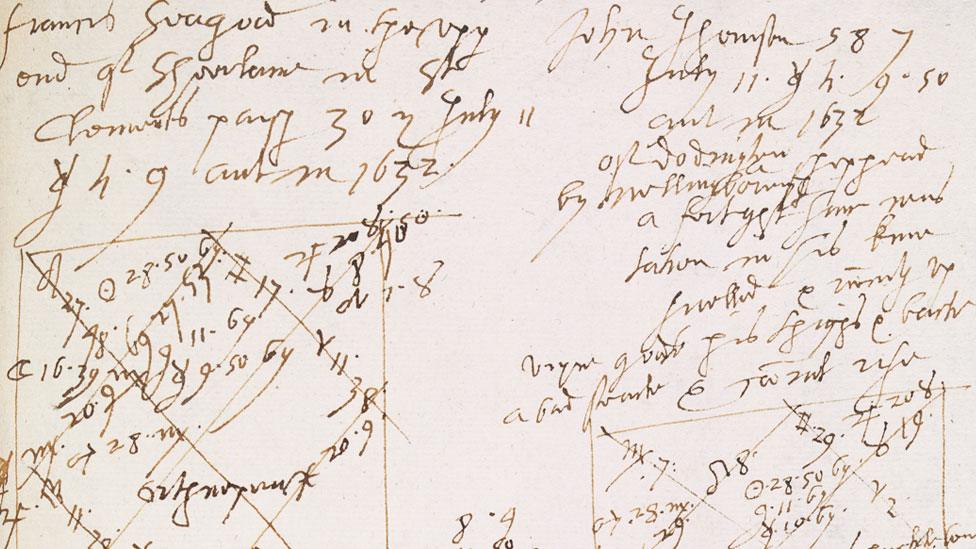

John Johnson, 58, of Doddington by Wellingborough, feared Agnes Watts, who looked after his sheep two years earlier, had bewitched him

Men were accused of witchcraft in the 16th and 17th Centuries, but figures suggest only 10 to 30% suspects were men.

Richard Napier, whose casebooks are housed at Oxford University's Bodleian Library, was officially the rector of Great Linford, but gained a reputation as a "physician both of body and soul".

Dr Carter said his treatments using star-charts and elixirs were "accessible to the average person" and he took reams of personal notes on his pre-Civil War patients.

"While complaints ranged from heartbreak to toothache, many came to Napier with concerns of having been bewitched by a neighbour," she said.

"Clients used Napier as a sounding board for these fears, asking him for confirmation from the stars or for amulets to protect them against harm."

Halloween is a time of reminders that the stereotypical witch is a woman, and the riskiness of "women's work", may be partly why, said Dr Carter

Most academic studies of English witchcraft are based on legal records, whereas Napier's records were only for his own reference.

Dr Carter trawled the recently digitised books, external and discovered only 2.5% of his casefiles were for suspected bewitchments.

Napier recorded 1,714 witchcraft accusations between 1597 and 1634. Among 960 suspects, 855 were women and 105 men. Most of their accusers were also women.

Dr Carter said: "England's mid-17th Century witch trials saw hundreds of women executed within the space of three years.

"Every Halloween we are reminded that the stereotypical witch is a woman. Historically, the riskiness of 'women's work' may be part of the reason why."

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

- Published31 October 2022

- Published24 February 2022

- Published30 October 2021