Stories of 'ordinary medieval folk' revealed in Cambridge bone study

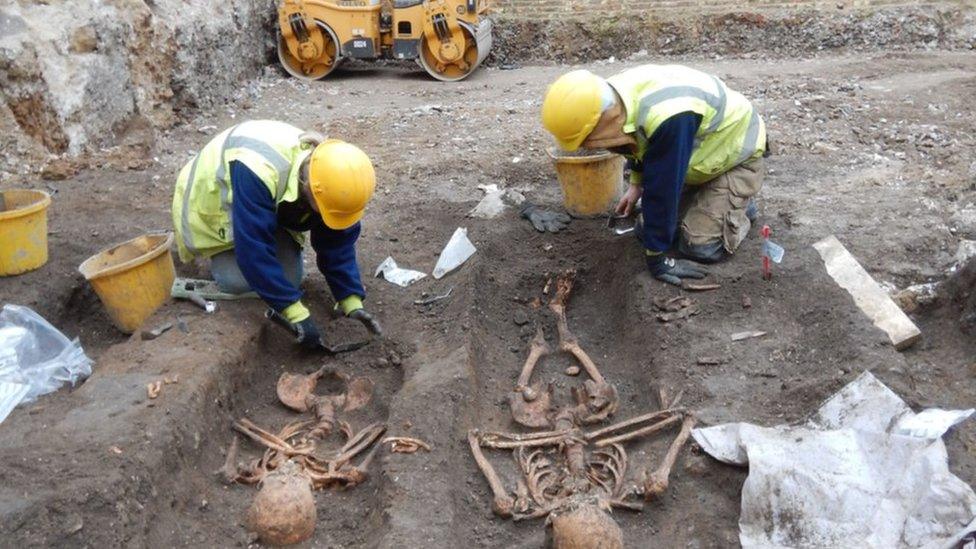

- Published

The remains of numerous people were unearthed on the former site of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist in 2010

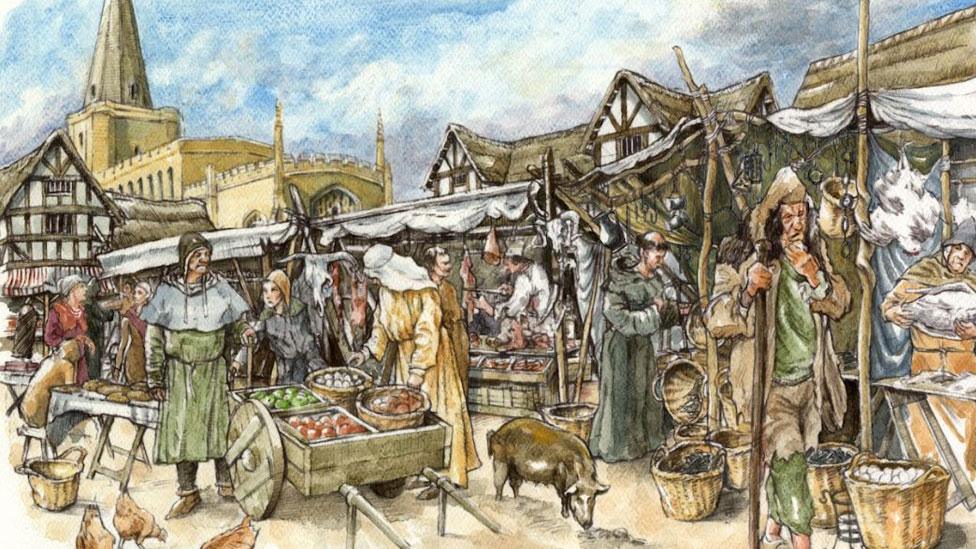

The stories of "ordinary folk" before and after the Black Death have been revealed through studying bones found in medieval cemeteries.

Archaeologists investigated the diets, DNA and bodily traumas of the remains of the townsfolk, scholars and friars of Cambridge.

The Cambridge University project analysed almost 500 medieval skeletal remains.

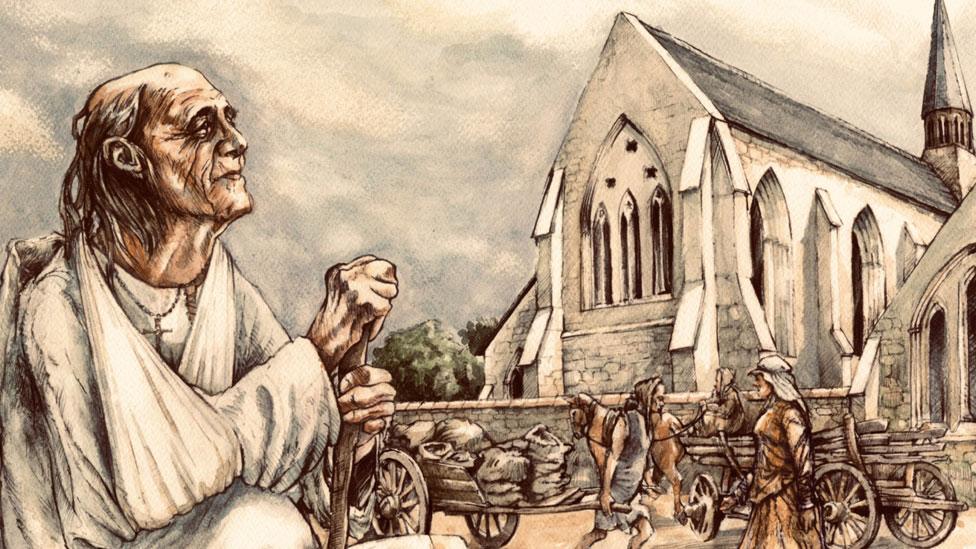

Prof John Robb said: "Like all medieval towns, Cambridge was a sea of need."

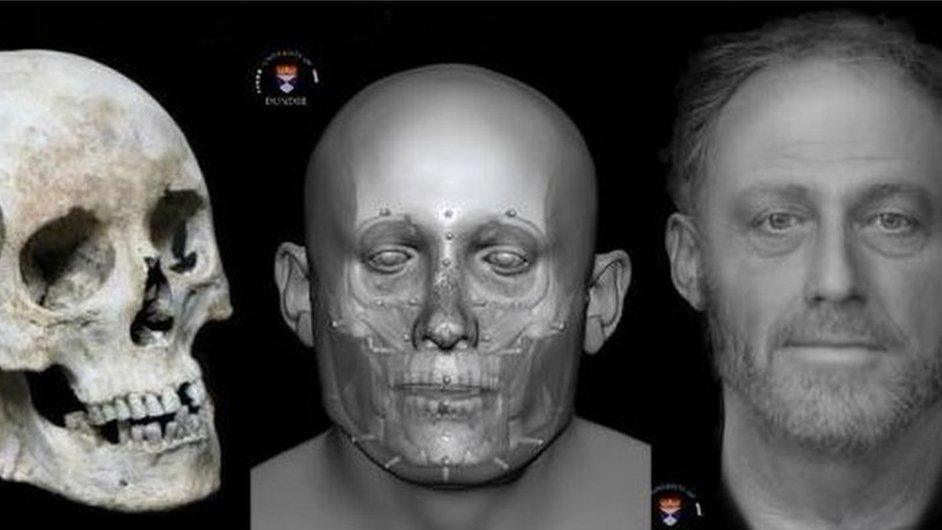

They include those of "Wat" as an older man, born between 1316 and 1347 who lived through the Black Death

"Christiana" was a young woman, born between 1256 and 1277 and who died between 1264 and 1308. Her life probably began in Norway

The samples, dating between the 11th and 15th centuries, came from a range of digs going back to the 1970s.

Dr Sarah Inskip, researcher on After the Plague, and now at the University of Leicester, said: "The importance of using osteobiography on ordinary folk rather than elites, who are documented in historical sources, is that they represent the majority of the population but are those that we know least about."

To make the samples "relatable", she said, the project drew on names found in medieval records to give pseudonyms to the people studied.

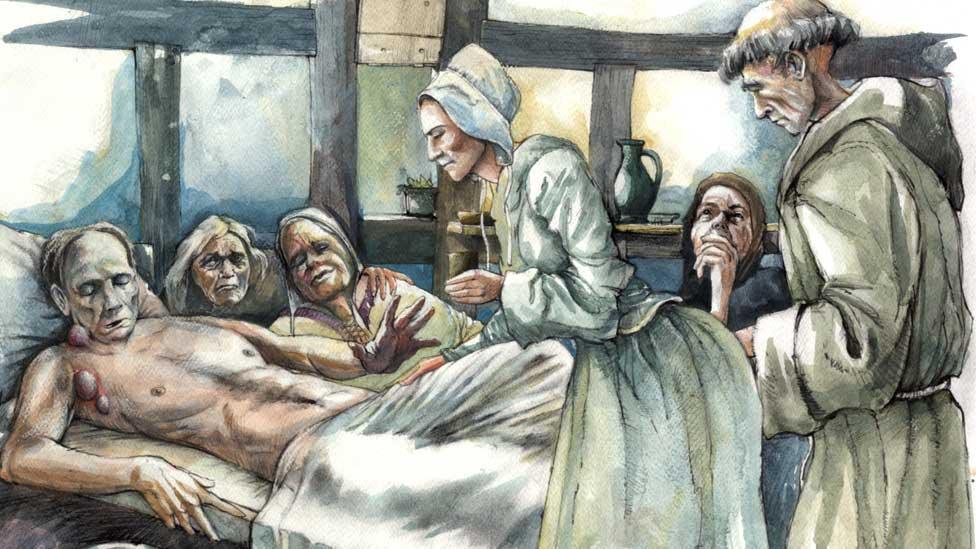

"Wat" was a man who survived the plague, dying with cancer at the city's charitable hospital, while "Anne" led a life beset with injuries, leaving her to hobble with a shortened right leg.

"Dickon", who died about 1349 in the first wave of the Black Death, probably lived through the Great Famine of 1315-1320 as a child, which may have stunted his growth

The Dickon skeleton contained plague DNA

Meanwhile, "Edmund" suffered from leprosy, yet was not separated from wider society, instead living with ordinary people to end up buried in a rare wooden coffin.

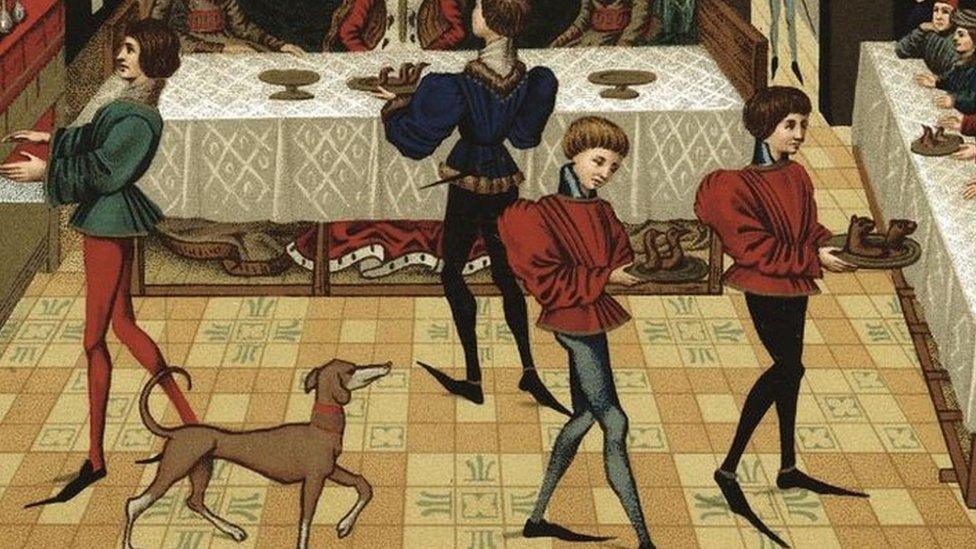

Almost all townsmen had asymmetric arm bones, with their right upper arm bone built more strongly than their left one, reflecting tough working regimes, particularly in early adulthood.

However, about 10 men from a hospital burial ground had symmetrical upper arm bones, yet had no signs of a poor upbringing, limited growth, or chronic illness.

Lead researcher Professor John Robb said: "These men did not habitually do manual labour or craft, and they lived in good health with decent nutrition, normally to an older age. It seems likely they were early scholars of the University of Cambridge."

Medieval Cambridge was home to just a few thousand people, but by 1400, that included between 400 and 700 scholars

While they did not have the "novice-to-grave support of clergy in religious orders", they were mostly supported by family money, patronage or earnings from teaching.

"As the university grew, more scholars would have ended up in hospital cemeteries."

Medieval Cambridge was home to just a few thousand people, but by 1400, that included between 400 and 700 scholars.

Bubonic plague or the Black Death hit Cambridge in 1348-9, killing up to 60% of the population.

The "osteobiographies" use all available evidence to reconstruct a person's life, Prof Robb said.

They are available on a new website launched by the After The Plague project, external.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published18 June 2021

- Published11 June 2021

- Published26 January 2021

- Published21 March 2017

- Published25 January 2017

- Published30 May 2016

- Published22 March 2013