Camelford water poisoning: the search for answers

- Published

Carole Cross died 16 years after Camelford's drinking water was contaminated

The resumption of the inquest into the death of Carole Cross has once again turned the spotlight on the small Cornish town which became the scene of the country's worst mass water poisoning.

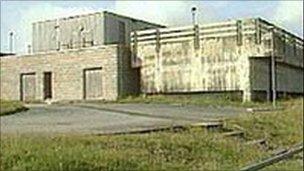

It is more than two decades since 20,000 homes in Camelford were affected when a relief delivery driver accidentally tipped 20 tonnes of aluminium sulphate into the wrong tank at the Lowermoor water treatment works.

The chemical, used to treat cloudy water, went straight into the town's main water supply.

The acidity in the water also released chemicals in pipe networks into people's homes

The water company was inundated with around 900 complaints about dirty, foul-tasting water but no warnings were given to the public on the night of the incident on 6 July, 1988.

Local residents subsequently reported suffering health problems, including stomach cramps, rashes, diarrhoea, mouth ulcers, aching joints and some even said their hair had turned green from copper residues.

'Considerable brain damage'

Less than 12 months later a Government-ordered report by the Lowermoor Incident Health Advisory Group said it considered it "unlikely in the extreme" that long-term effects from copper, zinc or lead would result from the short-term exposure Camelford residents had been subjected to.

In 1991, in a trial at Exeter Crown Court, the South West Water Authority was fined £10,000 with £25,000 costs for supplying water likely to endanger public health.

Three years later, in 1994, 148 victims of the incident reached an out of court settlement, with payments ranging from £680 to £10,000.

But the long-term health implications came to the fore in 1999 when a report in the British Medical Journal claimed victims had suffered "considerable damage" to their brain function.

A further official health inquiry was ordered by the then Environment minister Michael Meacher in August 2001.

Hallucinations claim

A draft report by the Committee on Toxicity (COT), published in 2005, said it was unlikely the chemicals involved in the incident would have caused any persistent or delayed health effects.

But it did recommend further research in a number of areas, including a study into those who did and did not drink the water.

No warnings were given to the public immediately after the contamination

Some members of the committee, which included Mrs Cross's husband, environmentalist Doug Cross, also claimed there was insufficient information available to reach a firm conclusion into the health affects of the poisoning.

Mr Cross said there had been "a great deal" of difficulty in gathering information.

His 59-year-old wife Carole died at a hospital in Taunton, Somerset, in 2004.

She had been living in the Camelford area at the time of the contamination and was referred to a neurologist a year before her death complaining of repeated headaches, hallucinations, difficulty in finding words and doing simple arithmetic.

In 2005 the West Somerset Coroner Michael Rose said a post-mortem examination had revealed abnormally high levels of aluminium in Mrs Cross' brain, who was found to have suffered from a rare form of Alzheimers.

In 2007 Mr Rose announced he was asking Devon and Cornwall Police to re-open the investigation into her death and that of another woman, 91-year-old Irene Neal from Rock, who died in June that year.

He asked the Chief Constable Stephen Otter to appoint a senior detective to look into allegations of what he called a "cover-up" over Camelford, saying "serious allegations" had been made in the media of a possible attempt to initially suppress the seriousness of the incident.

A year later Mr Rose criticised the government's lack of assistance over funding for further tests to research a possible link between aluminium and brain diseases.

In a statement, he said he had been forced to turn to Somerset County Council to pay for an expert investigation into the link because the government refused "to either finance or assist in such research".

At the time, the Department of Health (DoH) said the government had already commissioned a review of the potential health consequences.

The inquest into Mrs Cross's death was delayed to allow for further medical research to be completed.

It is expected to last two weeks.

- Published1 November 2010