Lost Gardens of Heligan: Teenager follows in ancestor's footsteps

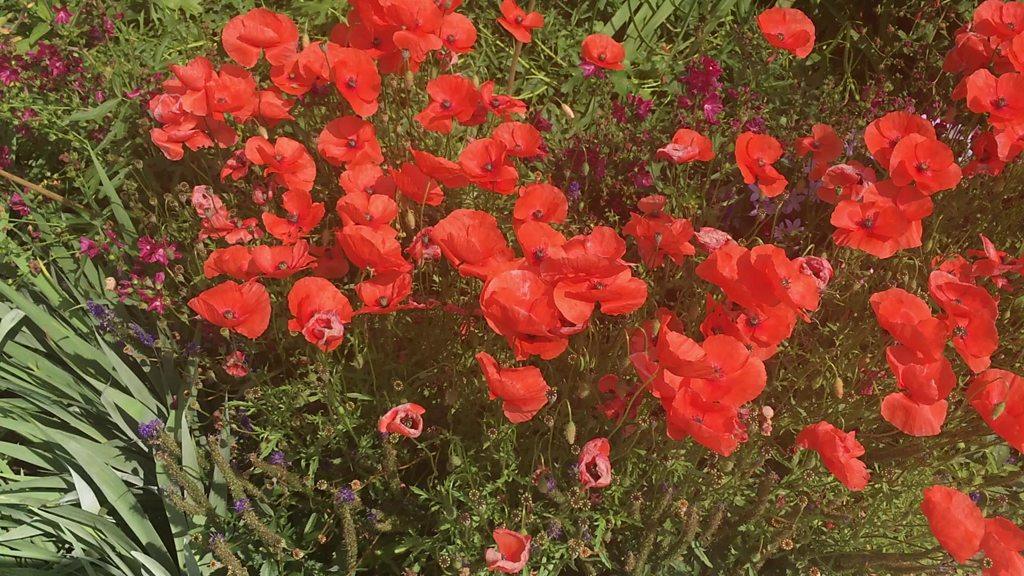

- Published

Toby Davies says he finds it "humbling" to be working in the same place his great-great-grandfather did

As Toby Davies digs, fertilises and prunes in a once lost garden he is working in the same place where his great-great-grandfather once toiled.

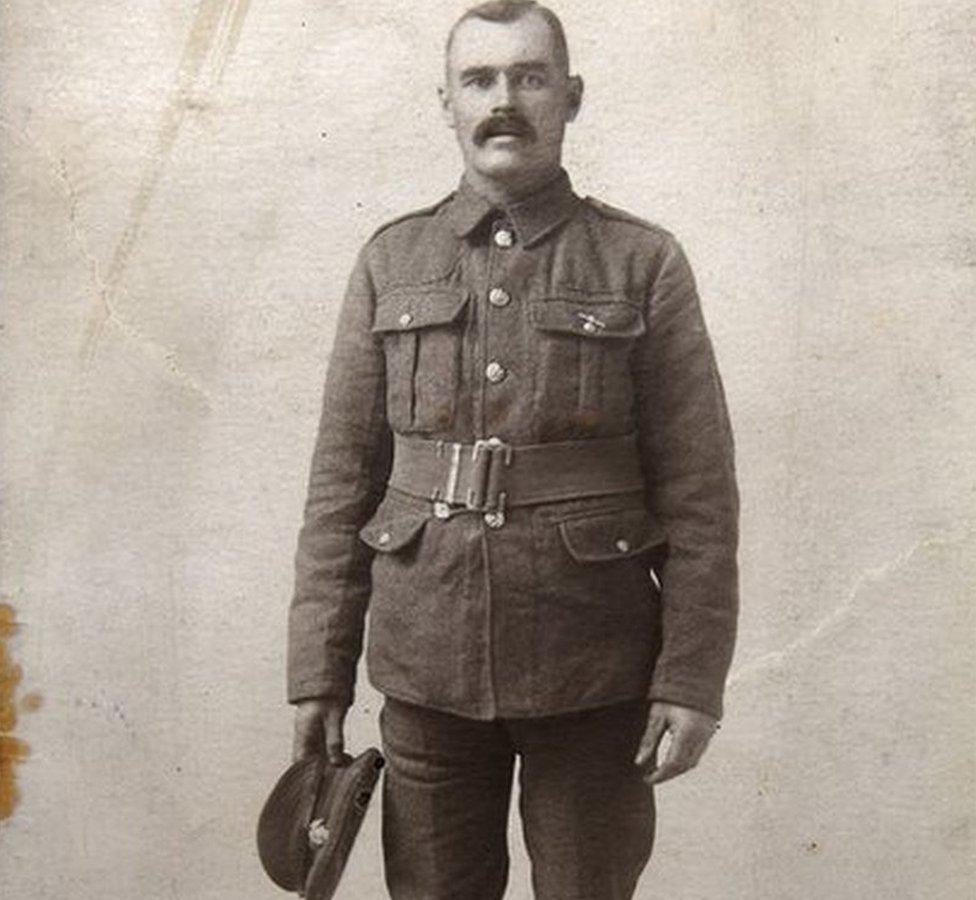

Charles Ball was one of nine men who never returned to the gardens of Heligan, near Mevagissey in Cornwall, having left to fight in World War One.

Pte Ball died on 24 April 1918 in France, 11 days after being wounded in action.

After the war ended, the gardens of the 200-acre estate were lost for decades - forgotten and overgrown.

Charles Ball suffered severe shell wounds to his chest and arm and was evacuated to the Canadian Military Hospital at Etaples where he died

The ancestral home of the Tremayne family for more than 400 years, Heligan Manor was used as a convalescent hospital for officers during World War One.

It was later used as a base for US troops during World War Two before being sold off and converted into flats in the early 1970s.

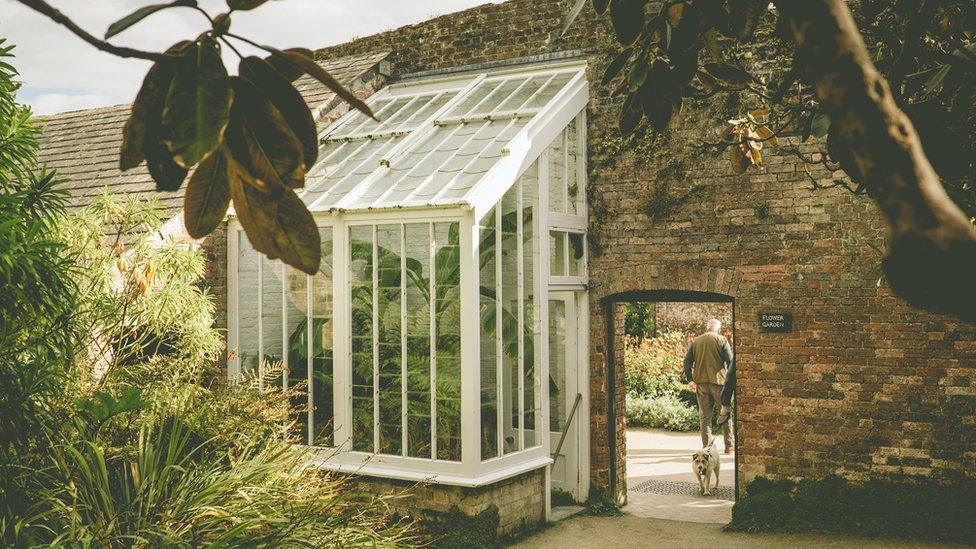

The gardens were rediscovered in 1990 by Eden Project co-founder Sir Tim Smit and Tremayne family descendent John Willis.

Under almost impenetrable undergrowth, fallen trees and rubble, they found the derelict structures that remained and in one small room - the old gardeners' toilet - the explorers found the signatures of those who left to fight, including Pte Ball's.

A decision was taken that any restoration would be done in their names.

Mr Davies, 19, is employed at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, now a popular tourist attraction, working in part to maintain his ancestor's legacy.

Eden project co-founder Sir Tim Smit and John Willis, a descendant of the Tremayne family of Heligan, rediscovered the devastated and mostly impenetrable gardens in 1990

Their explorations uncovered the Thunderbox Room - the old gardeners' toilet - inside of which they found a number of signatures and a date of August 1914. Other structures such as glass houses (pictured) were derelict.

"I just find it incredible how 100 years later my family still lives around here," said Mr Davies.

"I find it quite humbling to know that he was here all that time ago and that I have carried on in his footsteps."

Mr Davies, who is studying for a degree in conservation and countryside management, did work experience at Heligan in 2014 and then volunteered there while at college.

When he left for France Pte Ball left behind his wife Laura and their daughter Ena - Mr Davies' great-grandmother

Mr Davies now works in the estates team part time - similar to Pte Ball, who was in the Heligan records as a road man who was tasked with looking after the property's driveway.

He said it was his love of being outdoors that first attracted him to the work.

Now though, having discovered he and his ancestor shared a love of singing, Mr Davies says it feels as if it was "meant to be".

He finds working in his great-great-grandfather's footsteps "not all sad" but at times emotional.

Heligan House in 1912

In 1998 those involved in the restoration of Heligan started searching for relatives of the lost gardeners and found Pte Ball's granddaughter Barbara Palmer was still living locally

"We wouldn't be where we are without them," he added.

"Even walking down the driveway; it is what he did all those years ago and back in the day he wouldn't have been thinking 'maybe my family will be here'.

"I always think what he would actually think about it all.

"He was a really brave man."

How the estate's gardeners who went to war are still remembered

Mrs Palmer had an archive which included Pte Ball's service medals, a letter of thanks from the King and letters exchanged while her grandfather was in hospital after being fatally wounded

Heligan archivist Candy Smit said in the centenary year of the Armistice, the gardens were preparing to look forward rather than back.

"We spent a lot of time with relatives and they have shared everything they possibly could," she said

"You realise that everyone was a hero.

"They had to summon the courage to go out to the complete unknown."

She described the lost gardeners as "incredibly courageous" and "quite real to us" but said she believed their stories had now been told.

"We always intended the restoration to celebrate the lives of working people," she said.

"We have found out probably all we are going to find out and we have to use it to best possible effect now."

In one letter, dated 3 April 1918, the day of Pte Ball's death, Canadian service chaplain Captain WJ Parker wrote: "I trust that his dying wishes to meet you and your dear child again will be fully gratified in Our Father's House of many mansions"

- Published10 September 2018