How medieval Coventry was lost, say historians

- Published

While the bombing of Coventry did destroy its cathedral, the town's redevelopment was already well under way , say historians

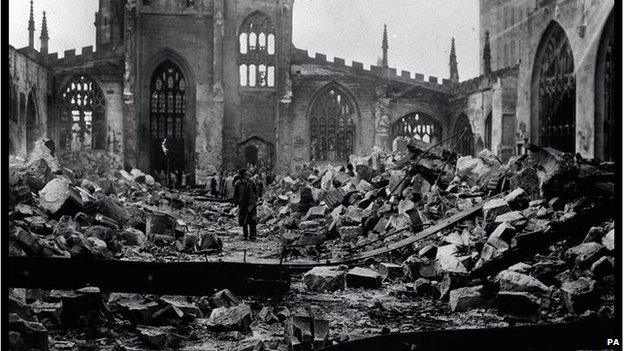

The cathedral was just one of many city centre buildings destroyed in the raids

Coventry 1940. Bombs were falling, sirens were shrieking and a 10-year-old boy was huddled in the cupboard under the stairs with his mum and his brother while his father was out fighting the fires that raged in the city's streets.

Today Albert Smith is in his 80s. But he still has powerful memories of the blitz which, 73 years ago, killed around 600 people and destroyed so much of the city he knew.

"I remember queuing outside Suttons Bakers the next morning," he said. "There was very little food available. Most of the big stores in Coventry had been destroyed. A few days later, I saw the cathedral ruins. They were still smoking.

"I had been in there for a wedding a few months before and I can remember how beautiful the interior was, with all its ancient history. All of that went."

Musical star 'furious'

Popular perception suggests it was World War Two that was responsible for the loss of much of medieval Coventry - a city known for its half-timbered houses and clusters of close-knit streets.

But Mr Smith and fellow historian David Fry say that, in fact, like other Midlands cities, Coventry was already undergoing a programme of redevelopment.

"Coventry Corporation - as the council was then called - spent most of the early 20th Century looking ahead, rather than looking back," said Mr Fry, who has written a number of books on the subject with Mr Smith.

"Just before World War One, the corporation had laid plans to redevelop the city's narrow streets.

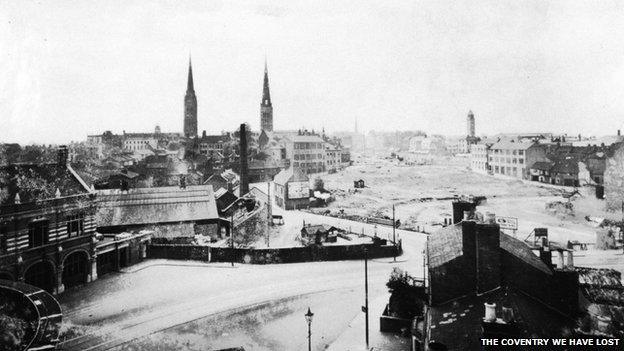

"In 1932 they began their plans and a few years later they demolished Butcher Row, a beautiful medieval street."

Popular perception suggests the war was responsible for the destruction of medieval Coventry but this demolition work began in 1936

Mr Smith recalls there was a lot of opposition to the city's redevelopment during the 1930s.

"There was a big outcry," he said. "They started knocking down a lot of the medieval area before the war.

One of the big musical theatre stars of the day, Gillie Potter, was furious about the loss of so many medieval buildings."

But Mr Fry said Coventry had suddenly become a "modern" city and the corporation considered the work necessary.

"Coventry hadn't been developed very greatly from the medieval period until the end of the 19th Century," he said. "All of a sudden, in the 20th Century, the city was given a turbo-boost by the opening of so many factories.

"It grew at a massive rate and it didn't have the infrastructure to deal with it."

The man who masterminded the rebuilding of Coventry after the savage bombing was Sir Donald Gibson but, according to Mr Fry, Sir Donald was already in talks with the corporation to redevelop the city before the war.

"Basically, the blitz gave him the opportunity to put that into action," said Mr Fry.

Even if Coventry's city centre had escaped the bombing, Mr Fry said he suspects much of the medieval city would have succumbed to town planners in the 1960s.

"Many medieval buildings were actually lost after the war, during the 1950s and 60s," he said.

"Projects like the ring road meant several historic buildings were moved to Spon Street, while others were demolished."

So how much of historical Coventry survives today? Mr Fry said there is still much to be found and the local authorities have become better at promoting what is left.

"Clearly the modern part of Coventry has suffered from decades of economic woes," he said. "But the area around the cathedral and the medieval guildhall do shed light on the historic side of the city.

"A bit more investment and promotion of that area may go some way to ameliorating some of the worst images of the city that have been put forward."