Writer tourism: The literary tourist trail hits and misses

- Published

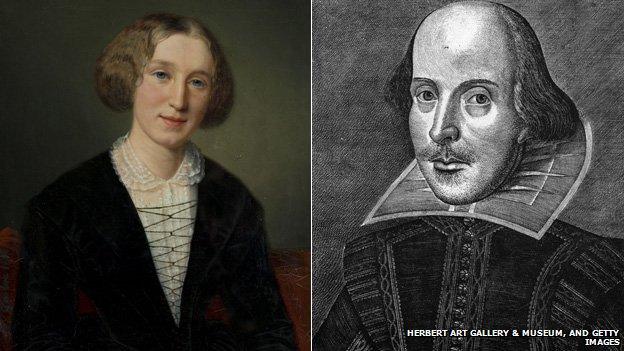

Nuneaton is failing to attract big crowds while nearby Stratford capitalises on its links with the Bard

Stratford-upon-Avon is expecting a tourism onslaught as it prepares for Shakespeare's 450th birthday celebrations next year.

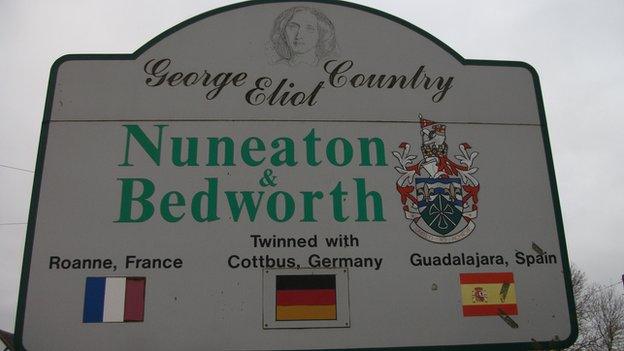

Thirty miles away in Nuneaton, fans of the Victorian novel-writing heavyweight George Eliot are struggling to draw the crowds. Why do some writers succeed on the tourism trail while others are left on the wayside?

"Oh look - you can buy As You Like It coasters," squeals an excited fan.

And that's not all. In the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust shop in Stratford-upon-Avon, they sell almost every Bard-based goody imaginable, from Anne Hathaway's Cottage Teapot to an Alas, Poor Yorick skull-shaped mug.

It may be a drizzly winter weekday, but Stratford is heaving with tourists, wandering up and down Shakespeare Street and into the town, past Falstaff House and Iago's Jewellers.

In Stratford, the shops are crowded with tourists

"You can see Shakespeare's influence everywhere," says James Wilkinson, one of four University of Leicester English students who are in town to see Anthony and Cleopatra.

"Stratford is a lovely town. The buildings are so old and beautiful. It's a great place to come."

It is possibly unfair to compare the man widely considered the world's greatest literary genius with one of his fellow Warwickshire wordsmiths George Eliot (real name Mary Ann Evans).

But fans of the Nuneaton novelist, whose work Middlemarch has a claim to being one of English literature's greatest novels, can only look at Stratford with envy as they try to tempt the crowds across the Avon and up the road.

John Burton is chairman of the George Eliot Fellowship, which spent most of 2012 trying to save part of George Eliot's childhood home from demolition.

"If they even found a brick at Stratford that was related to Shakespeare, they would be fencing it off and turning it into a tourist attraction," he says.

Luckily, the site's owners, Whitbread, had a change of heart and have now agreed to donate £85,000 towards creating a George Eliot visitor centre on the site. Mr Burton hopes it will open in 2014.

"I think Whitbread weren't aware they had such an important building on their estate," he says. "We have a committee working to refurbish the building and we hope that will make a big difference to what the town can offer."

Shakespeare's birthplace is now a major tourist attraction but Victorian campaigners had to fight to save it for Stratford

According to figures from Visit Britain, Stratford attracted 82,000 international tourists in 2012

At the moment, Nuneaton's offering seems fairly limited compared to Stratford's. The town has a George Eliot Hospital and an Eliot Business Park, neither of which are likely to appeal to tourists.

The library has an extensive collection of the writer's work, including several first editions, while there is also an exhibition devoted to Eliot at the town's museum and the trust gives regular guided tours and walks.

But according to figures from Visit Britain, Stratford attracted 82,000 international tourists in 2012, while Nuneaton achieved just 6,000.

Mr Burton admits Nuneaton, an industrial town, may not strike many as the most picturesque of destinations.

But if it made more of Eliot's appeal, he thinks it could prove a huge boost to the area.

"A lot of people say she was to the novel what Shakespeare was to drama," he says. "When Andrew Davies adapted Middlemarch for the BBC in the early 90s, it was hugely popular and I think a lot of people would be interested in finding out more about her."

There are several buildings in the area that have connections with the writer, including The Griff, now a pub, where she lived for 22 years and Arbury Hall, a country house estate where Eliot's father worked.

For now, there remains a gulf between Nuneaton's offering and the wealth of attractions in Stratford.

"Stratford maximises its Shakespeare connection," says Peter Lee, chair of the Nuneaton Civic Society.

"A lot of its tourism isn't based on Shakespeare himself but more on an experience of Shakespeare. That's what Nuneaton misses out on. There is no central place in the town where people can go to find out about her."

But even Stratford struggled to hang on to its greatest assets. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, which oversees the Bard's birthplace, was formed in the 1840s in order to save the building being sold and, potentially, transported overseas.

Charles Dickens was one notable campaigner.

"I don't see why Nuneaton couldn't become like Stratford," says Paul Edmonson, head of research at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. "Ours is a rescue story too. People started visiting Stratford in around the 1770s and this house became the first of a number of literary shrines.

"The literary tourism industry is huge now because writers like Shakespeare have an international appeal.

"George Eliot's understanding of humanity is very powerful and comparable to Shakespeare. She's also a reminder genius doesn't necessary grow in beautiful places."

Eliot fans say Nuneaton needs to make more of its literary connection

The George Eliot Hospital is one of several buildings in the town named after the author

However, others think Nuneaton's transition to a tourist trap could prove trickier.

"Shakespeare has been canonised for centuries, which gives him an unfair advantage in some ways," says Pablo Mukherjee from the University of Warwick's English and comparative studies department.

"Eliot is obviously a novelist of ideas - to the extent that she had to write under a pseudonym because of of the anxiety her work would not be accepted as that of a woman.

"It is difficult to build a cult of tourism around that spiky kind of writer, with their commitment to difficult ideas. Shakespeare is studied throughout the world and his ideas can be translated into so many different media. There is an idea of Englishness attached to him and when you go to Stratford that's what you find - an idealised version of Englishness."

Some of Stratford's international tourists say they would be willing to travel up the road to Nuneaton

Stratford is already busying itself in preparation for the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth next year.

The Royal Shakespeare Company, which has its headquarters in Stratford, and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust will run events throughout the year and are readying themselves to welcome thousands more visitors.

What about those coaster-buying crowds? Could they be persuaded to venture slightly further afield to investigate another famous writer's hometown?

"Nun-neaton?" asks a puzzled Marzia D'Amico, 24, a student from Italy who has arrived in Stratford "for the experience".

But when she hears it's George Eliot's birthplace, her expression changes. Is she an Eliot fan?

"It's about the name," she says. "When you hear about these great writers, you want to know more. And when you read the books, you want to be able to picture the places they're describing."

- Published26 June 2012

- Published13 November 2013