The Coventry Blitz: 'Hysteria, terror and neurosis'

- Published

The raid sent the people of Coventry into a state of shock

On 14 November 1940 the Luftwaffe launched its most devastating bombing raid of the Second World War so far. The target was Coventry, a manufacturing city in the heart of England with a beautiful medieval centre. The result was a shocking collapse of social order that caused thousands to flee and challenged notions of Britain's "Blitz spirit".

As dawn broke over a ruined city, a horrific scene of destruction greeted the survivors. Homes and factories were flattened and many buildings were consumed by flames so intense, the city's sandstone brickwork glowed red.

The air stank of burning flesh, and bodies, some mutilated beyond recognition, lay in the streets.

Amid the broken walls and burning buildings, a 14-year-old girl was making her way to school.

Jean Taylor had spent 11 hours crouching in the corner of a bomb shelter, among arguing adults and wailing children, the atmosphere becoming ever more fetid and fearful.

Hundreds of tonnes of bombs had been dropped on the city. As Jean emerged from the shelter on Masser Road she gazed helplessly around the broken streets.

She said: "I saw a dog running down the street with a child's arm in its mouth. There were lines of bodies stretched out on blankets.

"A poor fireman was watching helplessly while the buildings were still burning."

The most notable building to be destroyed in the raid was Coventry's medieval cathedral, St Michael's

Across the city, people were crawling out from under-stairs cupboards and hastily-made bomb shelters.

What they found sent the city into a state of shock and, in some cases, a hysteria that has not been recorded in any other British wartime city.

Tom Harrisson, an anthropologist who arrived in Coventry soon after the raid, said: "Women were seen to cry, to scream, to tremble all over, to faint, to attack a fireman and so on."

Harrisson had set up a project in 1937 called the Mass Observation Unit, a social research organisation aimed at recording everyday life in Britain.

The unit's investigators - who worked with the Ministry of Information - were "storm-chasers", arriving at scenes of devastation to record the mood on the ground.

He documented scenes of "unprecedented dislocation and depression".

People "didn't know where they were or where they were going", eyewitnesses recall

Harrisson wrote: "The overwhelmingly dominant feeling was utter helplessness. The tremendous impact of the previous night had left people practically speechless in many cases.

"There were more open signs of hysteria, terror, neurosis, observed in one evening than during the whole of the past two months in all areas."

Historian Dr Henry Irving, an associate fellow at the Institute of English Studies, said: "What Harrisson describes is a psychological desperation and helplessness.

"In Coventry he describes something that is on a scale that hasn't been seen before."

This reaction was exactly what the government had feared.

Matt Brosnan, a historian from the Imperial War Museum, said: "The government was worried aerial bombardment could destroy civilian morale, and perhaps in Coventry those fears were put to their sternest test."

The Luftwaffe even had time to film the bombing

German historian Dietmar Süß said: "The idea that masses in a state of terror ceased to behave humanely and became transformed into a violent mob verging on the bestial was a widespread assumption."

And while that assumption may have been unfounded, to people in the city the wild rumours that followed the raid were highly distressing, sparking fear and panic.

In the days after the bombings, the local paper was forced to deny that people remained trapped beneath collapsed buildings and that some of those buried were still alive and being fed "by tubes".

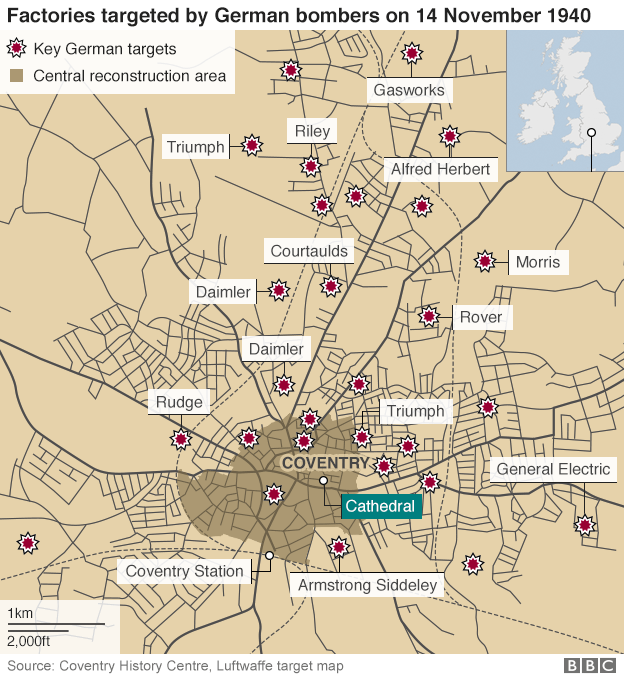

Map shows key factories, as well as local gasworks, targeted by the German Luftwaffe on 14 November 1940

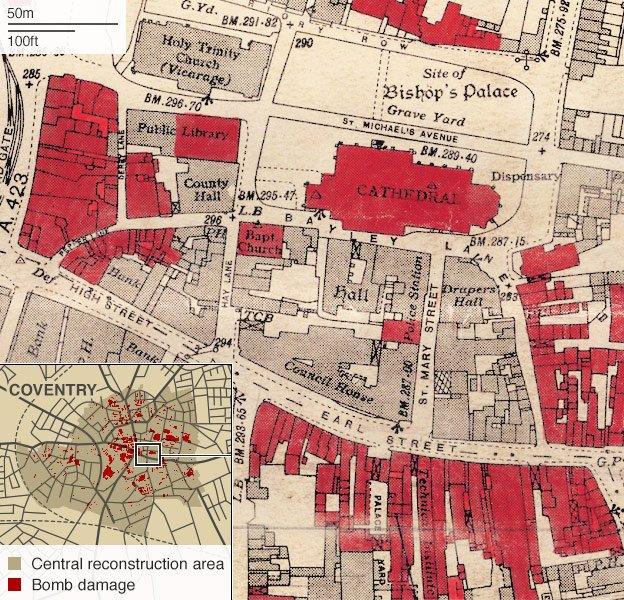

The map is an excerpt of one produced after the 14 November raid showing buildings damaged in the city centre

'The BBC is out of control' - a government's fury

When the BBC broadcast an interview with Harrisson, on 16 November, it caused anger inside Winston Churchill's cabinet.

"Harrisson spoke about the number of casualties, the dislocation and shock people felt and the sense they had been let down by the government," Dr Irving said.

"It's that that gets picked up on by high-up members of the government."

Cabinet documents of the time show Secretary of State for War Anthony Eden describing the broadcast as "most depressing", adding it would have a "deplorable effect" on morale.

The Coventry bombing turned out to be a trigger-point for the government, and ministers were determined to exert more control over the BBC.

Dr Irving said: "In the end, a compromise was reached and two government-appointed liaison officers were placed inside the BBC.

"But it was the closest the BBC came to being taken over by the government - and it could have gone much further."

Margaret Batten, who temporarily lost her sight after being buried in a bomb shelter that night, remembered Coventry as a city of lost souls.

She said: "People's nerves were absolutely shattered. My brother-in-law Reg, who lost his sister and his father, was so shocked he walked eight miles to Kenilworth with his jacket all charred from the flames.

"He didn't know what he was doing."

Without transport, water, electricity, gas - the fabric that holds the life of a city together - things were falling apart.

The fabric of the city was falling apart

A mass grave was dug for Coventry's dead

Eileen Bees, whose family of 14 were bombed out of their home on Clay Lane, recalled: "The streets were running with water.

"There were ambulances and buses taking the injured to hospital - people were all bandaged up.

"Some were digging to try to help those who had been buried in their homes.

"Others were walking about looking absolutely shell-shocked. They didn't know where they were or where they were going."

Food was scarce and people were panicking.

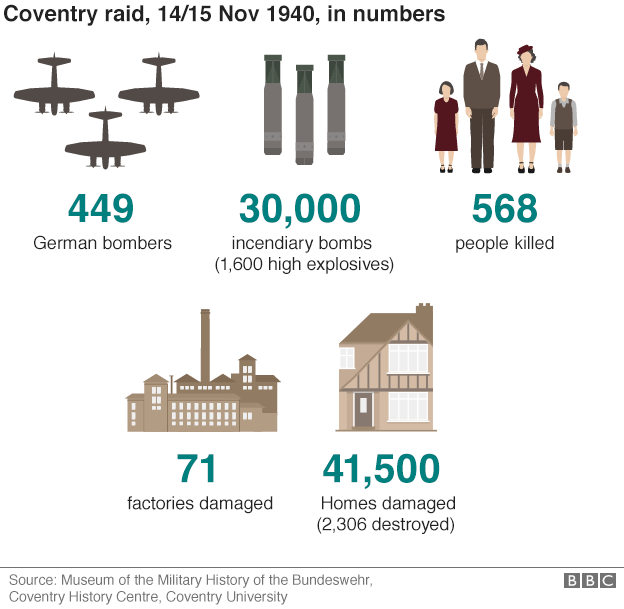

Numbers vary for the number of people who died in the raid and the buildings damaged - but these are the figures most commonly quoted

Mrs Bees' father broke into a cooked meat shop to find food for his hungry children.

"The owners came back and were terribly angry to find us there," she said. "But my dad would never have done that if he hadn't had to."

Harrisson said nearly everybody knew somebody who had been killed or was missing. He wrote: "This brought the whole thing home more fiercely to everybody.

"This helplessness and impotence only accelerated depression. On Friday evening, there were several signs of suppressed panic as darkness approached.

"In two cases, people were seen fighting to get into cars which they thought would take them out into the countryside, though, as the drivers insisted, they were just going up the road to the garage."*

During the course of the night, 41,500 homes had been damaged.

Amid the wreckage of their once beautiful city, the people of Coventry were making their way to work

The city's medieval cathedral was destroyed

In the aftermath of the bombing, more than half of the city's population fled the city, streaming out into the countryside to stay with friends or relatives or - in some cases - to sleep in fields.

Ivy Cumberlidge, who was 19 at the time, said: "There were so many houses destroyed that people used to walk out into the countryside at night, then come back into the city to work during the day,"

The authorities estimated there were 2,500 homeless people.

Alan Hartley, a teenager at the time, remembers feeling betrayed at the streams of cars and people on foot leaving Coventry.

He said: "We felt a bit peeved, I remember. It was as if they were leaving us to defend it."

Visitors to the city found scenes of "unprecedented dislocation and depression"

Amid this crisis, what had become of the "Blitz spirit" that in Britain has become a defining national story of World War Two?

Psychopathologist and historian Prof Edgar Jones, from King's College London, said Coventry's experience was extreme. Other cities, such as London, Liverpool, Birmingham and Bristol, had been bombed but did not suffer the same degree of social collapse.

He said: "We do not see these examples of panic in other cities."

He believes the civilian population in Coventry displayed far more symptoms of "inappropriate, anxiety-driven behaviour" than shown by people in other bombed British cities.

"This is a big raid that comes out of the blue. There is no warning. Such was the intensity of the raid that two-thirds of the buildings in the centre of Coventry were destroyed.

"Cities like London, Birmingham and Liverpool were much larger so the effects of the raids were less intense.

Some of the survivors of the onslaught have described their experiences

"To get a raid of such intensity was a shock to the system."

So what was it about the Coventry raid that made its effects so much more mentally dislocating than attacks on other British cities?

Historian Frederick Taylor says there was a feeling of betrayal among Coventry's residents at "perceived council negligence".

He said that a failure by the authorities to prepare for the war meant there was a lack of emergency water supplies. This thwarted firefighting efforts and led to considerable extra destruction, most notoriously in the case of the cathedral.

And while cities like Dresden would lose many thousands, rather than hundreds, of civilians to bombing raids, Mr Taylor believes the destruction in Coventry was very personal.

He said: "Everybody knew each other.

"People died together in air raid shelters, whether it was the Anderson shelter in the garden or under the kitchen table.

"When you see six people with the same surname at the same address who died, and about half of the bodies were unidentifiable, it takes on a terrible intimacy."

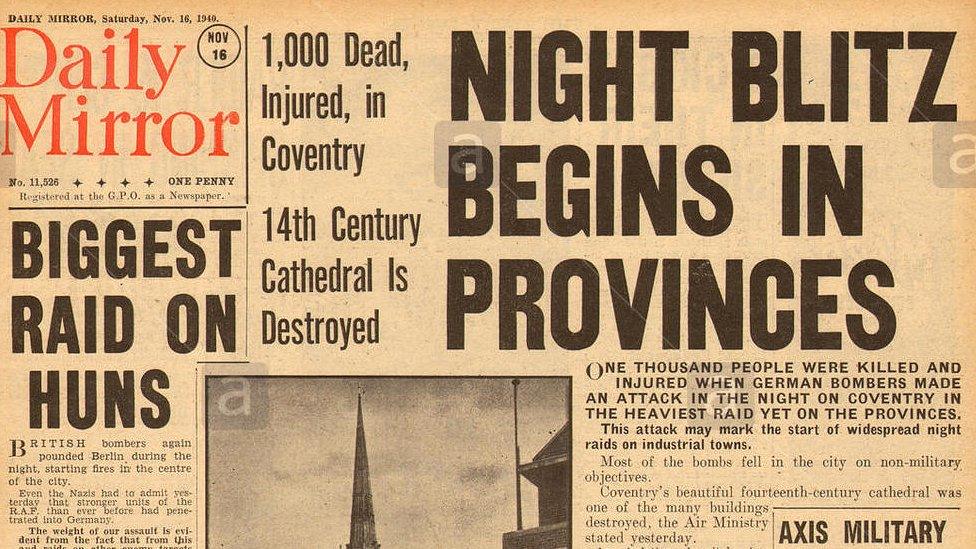

The news of the attack was widely reported

But early on the evening of 14 November 1940, the horrors that were soon to befall the people of Coventry were still unimaginable.

If you had visited Coventry that day, you would have experienced a city that was fairly typical of 1940s Britain.

Boys were kicking footballs around on playing fields.

In the medieval city centre - its winding, half-timbered streets among the best-preserved in England - young couples were heading to dance halls. Crowds were flocking to the cinemas.

The city had expanded dramatically in the 1930s, with big factories such as Armstrong Siddeley, Daimler and Humber - which nestled cheek by jowl with the city's shops and houses - producing first motor cars and then, with the onset of war, aircraft parts.

Workers were on their way home to the newly-built 1930s semis that spanned out to the suburbs.

And then the sirens sounded.

Alan Hartley, who was 16 at the time, said: "They were so loud, they enveloped the whole city."

Too young to fight, Mr Hartley - like many of the teenage boys in his area - had volunteered for the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) organisation.

He said: "We were set up to fight incendiary bombs and look after people during an air raid."

He immediately ran to his post.

Nearly everyone knew somebody who had been killed or was missing

'A concentration of fire'

The conditions on the night of 14 November were "perfect" for bombing

The Luftwaffe's attack on Coventry was one of the heaviest and best-targeted raids up until that point.

British intelligence had discovered days earlier a raid - codenamed Moonlight Sonata - was planned for the night of the next full moon, 14 November. But they did not know the target.

The Germans had adopted a new communication system that the Allies could not read or jam.

This left Coventry reliant on Britain's "completely inadequate" anti-aircraft defences.

There were no aircraft or guns equipped with radar to combat a night-time raid.

Prof Neil Forbes, of Coventry University, said: "Everything was in an appalling state as far as Britain was concerned.

"Britain's air defences were poor. All of that would be dramatically improved by 1941 but in 1940, Britain was simply not prepared."

Unteroffizier Gunter Unger, who took part in the raid, said: "I have never come across such a concentration of fire during a raid, not even in London."

The intensity of the raid was a "shock to the system"

At first, the raid was only a purple warning - meaning aircraft were in the vicinity. But then, the warning turned red. Aircraft were overhead.

One of Mr Hartley's friends shouted at him to look up at the sky.

The boys could see a parachute flare [launched by the Luftwaffe to provide light] in the sky over Radford, a suburb about two miles north of the city centre.

Mr Hartley said: "Then I saw another and another until the whole city of Coventry was circled by these flares."

Coventry's medieval city centre was badly damaged

"All you could see was the searchlights. Occasionally, as they were swinging around, suddenly you might see a little silver dot and you would know it had picked up one of the planes. Then it would vanish. It was strange, seeing these little glimpses of the people who were bombing us."

The Coventry raid was one of the first to use Pathfinders, a squadron of 13 planes, named Kampfgruppe 100, that flew in advance of the main fleet.

The Pathfinders would drop incendiary explosives to start fires that would guide the bombers to the city.

German historian Jens Wehner said: "The Nazi strategy was to make terror.

"The Pathfinders made at least eight big fires in Coventry so the bomber crews could see it a long time before they reached the city."

Gunter Unger recalled that the bombers set off from an airbase at Abbeville, in northern France.

Unteroffizier Gunter Unger took part in the raid

Alan Hartley was a young ARP volunteer

He told the BBC in a 1977 interview: "As we were flying over the Channel, we could clearly see Coventry burning, so the use of radio aids was practically unnecessary.

"We attacked at about half past two at night and there was no defence. There was very little flak and no night-fighters and, when we reached the target, there was a huge sea of flames."

Once the city was blazing, crews sought areas that were not already alight to drop their bombs.

Mr Wehner said: "The first raid dropped high explosives - bombs that made big explosions intended to destroy the roofs of buildings and knock out utility services such as gas, electricity and water."

On the ground, the people of Coventry were fleeing for cover, including children, most of whom had not been evacuated from the city.

German-Jewish refugee Anne Shearer had lived in London before moving to Coventry - where she said the raid was more intense

Margaret Batten was buried in an air raid shelter

Anne Shearer, an 18-year-old German-Jewish refugee, was cycling home from the cinema where she worked when the bombs began to fall.

She said: "We dived under the table in the kitchen and stayed there for the whole night."

Before moving to Coventry, she had lived through the Blitz in London.

Mrs Shearer said: "The Coventry Blitz was far worse than anything there.

"It was so much more concentrated. In London the bombs dropped every 15 minutes, but here it was constant. They literally dropped it all in one night."

The Germans were met with so little defence that some had time to return to their bases in France to collect more fuel and explosives.

Margaret Batten ran, with her sisters, to an air raid shelter on Forfield Road.

Not long after they arrived, there was a direct hit on the shelter.

Miss Batten said: "I was sitting on a neighbour's lap and I got thrown forwards as she got thrown backwards."

The neighbour, a woman with twin girls, died from her injuries.

Miss Batten said: "I lay, buried in rubble, crying for my mum. I can't remember how long I lay there in the dark. People were screaming and terrified."

The damage was on a scale that had been inconceivable before the raid of 14 November

The propaganda war

Joseph Goebbels, seen here conferring with Hitler, masterminded Nazi propaganda

Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels was inspired by the raid to coin the word "Koventrieren"- to "Coventrate", or to annihilate or reduce to rubble.

A Boy's Own-type novel published in Germany - "Bomben Auf Coventry" (Bombs on Coventry) - describes a heroic pilot named Werner Handorf setting off to avenge a "cowardly attack on Munich" carried out days earlier by the Allies.

"Here begins the path which will lead England - who unscrupulously broke the world's peace - into the abyss," the author writes.

But shortly after the raid, the Berlin hierarchy became alarmed at the triumphant tone of German reporting.

Historian Frederick Taylor believes part of the reason for their unease may have been the way the attack was perceived in the US, where the New York Times bore the headline: "Cathedral is destroyed".

The Christmas service among the ruins of Coventry Cathedral was broadcast around the world and pictures of the ruined place of worship became symbolic of Nazi aggression.

Mr Taylor notes in his book, Coventry, that the New York Herald Tribune wrote: "No means of defense which the United States can place in British hands should be withheld."

By December 1940, 60% of Americans said they would help Britain - even at the risk of being drawn into the war.

Across the city, Eileen Bees' family were huddled in their living room.

She said: "At first, it was very quiet but then... it really got going.

"A bomb came down at the back of the house which blew the glass out of the windows.

"Then another bomb went off at the front of the house that brought those windows in.

St Michael's was elevated to cathedral status in 1918 but 22 years later lay in ruins

Despite the loss of so many lives and city landmarks, Coventry was able to recover

"All the glass came in on my back and my older brother Bill pulled me on to the floor. We were all screaming and crying.

"Bill said: 'We have to get out of here' but the front door had become jammed with the bomb blast and he couldn't open it."

Eventually, neighbours came to break the door down.

Mrs Bees said: "We ran down the road to the air raid shelter. I can remember the glass crunching under our feet.

"I looked up at the sky and it was the reddest sky you can imagine, with the searchlights moving through it."

Eileen Bees' family were trapped in their home while the bombs fell

Three-quarters of the city centre - including the ancient cathedral - was ablaze.

A report said that "pressure on the mortuary service was so heavy that at one point, they were seeing 60 bodies in one hour. Some 40 to 50 were unidentifiable, owing to mutilation".

The city's defences were overwhelmed and those fighting fires were themselves being killed or severely injured - the head warden at Alan Hartley's Air Raid Precautions post among them.

Mr Hartley said: "We tried to phone for an ambulance but the lines were down.

"So I decided to grab my bike and my tin hat and ride into the city to get help. There was nobody else."

The teenager hurried through the streets, dodging pieces of searing shrapnel. As he neared the centre, he found a city ablaze.

He said: "The houses on both sides of the street were burning.

"The cathedral was on fire and the walls were glowing red."

It is believed 568 people died in the bombings, with a further 1,256 injured. Yet, within weeks of the raid - and contrary to all expectations - the city revived. Factories were soon turning out aircraft parts that would be used to avenge the attack.

Despite the deprivation, production soared.

Arthur Alfred Fennell, a factory worker, recalled: "I remember there was a feeling among some that we wanted revenge.

"In the nights, you didn't know if you'd still be left standing, so you went to work in the mornings determined to do your absolute utmost for the war."

Ivy and Thomas Cumberlidge vowed not to "lie down", despite losing friends and their home

Ivy Cumberlidge, whose home was destroyed, said: "We lost a lot of family friends and it took a while to get over it.

"But my husband said: 'We are not lying down to this.' I got a job making the pistons for the Spitfires. My dad didn't like me doing it but it felt important to be helping with the war effort."

How had Coventry's deeply traumatised residents been able to recover?

Prof Edgar Jones believes it took just a few days for the Blitz spirit to come to the fore.

He said: "The Blitz spirit was not a myth. People recovered and got their nerve back and returned to a semblance of normality."

For those who had lost loved ones, Coventry's close-knit community helped them get through this very worst of times.

A mass grave was dug to bury all the dead.

The dead were buried in a mass grave

Miss Batten said: "It was like a trench, one big long grave, with the bodies wrapped up next to each other.

"You never really get over it. But everybody used to pull together in those days and I think that was what got us through."

Eileen Bees said: "A lot of sharing went on.

"Because we were a big family, Mum would give some of our share of rations to others who didn't have as much. People would swap things like tea and butter with their neighbours.

"I think that kept the community together, in a way. People rallied round."

Within weeks of the raid, the city revived

In the days following the attack, both King George VI and Churchill visited the city.

Mrs Bees said: "People made a very big thing about that.

"But I don't think that meant very much to us. When you are homeless and you have nothing to eat, you have more important things on your mind."

Prof Jones points out that, even in the face of a devastating assault of the nature experienced in Coventry, communities find ways to rebound.

He said: "Communal living helps people to recover - I believe it's in our biology.

"You see that in the ways people responded in 9/11 - there are stories of those in the towers helping each other in a very orderly way down the stairs to safety."

An estimated 25,000 people died in Dresden

Yet a few years later, the Allies were working to "Coventrate" German cities like Hamburg and Dresden.

Mr Taylor said: "There was no direct "revenge" motive as people often think - it happened, after all, four years later.

"However, undoubtedly, if Coventry was the blueprint, then Dresden's fate was the perfected 'product', and a very terrible thing it was too."

In four raids between 13 and 15 February 1945, the British and Americans dropped more than 3,500 tonnes of bombs on Dresden, killing an estimated 25,000 people.

But Prof Jones argues that just as the Blitz spirit in Coventry meant civilians did not capitulate to the enemy, so too did that hold true in Dresden and also in Hamburg - where more than 40,000 people were killed in a single week of Allied bombing.

He said: "The British and the Americans had done a lot of careful calculations, based on battlefield figures, about the number of people required to be killed or wounded in order to prompt psychological breakdown among the rest - in other words, the level of attack you need to provoke a surrender.

"They believed the Germans' mistake was that they had not bombed British cities enough, which is why we see much higher casualty rates in German cities."

Many of Coventry's half-timbered streets were destroyed in the raid

Yet, he added, the German surrender was prompted by the arrival of troops on the ground - not airstrikes.

He said: "The popular view is that civilians were inherently weak - they did not wear uniforms, they had no training, they would fall apart under pressure.

"But World War Two demonstrates that civilians are much more resilient than people think. They work in communities and are actually very resourceful."

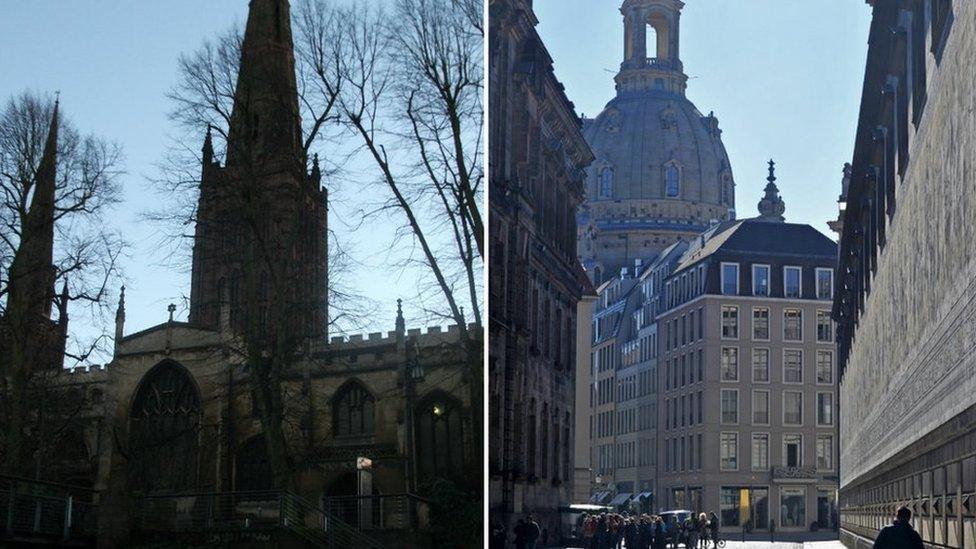

Coventry and Dresden are now twinned

After the war, the communities of the two cities that became symbolic of the devastation - Coventry and Dresden - were twinned.

Today, in the grounds of Coventry's ruined cathedral stands a sculpture presented to the city by Dresden's Frauenkirche - its landmark church that was destroyed in the war and later rebuilt.

Mr Taylor said: "The relationship between Coventry and Dresden is a fine thing, one that allows a little faith that human nature can sometimes change and get better.

"I know from my contacts with survivors of both raids that the desire for reconciliation is very genuine."

* Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown, London on behalf of the Estate of Winston S. Churchill. Copyright © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill