MND: Daughter caring for father plans charity

- Published

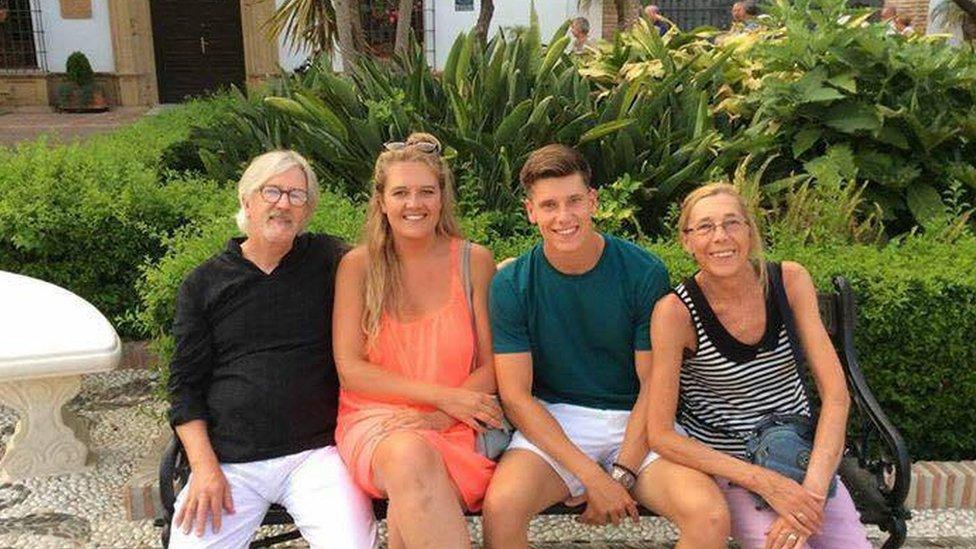

The Gibson family before Guy, 66, was diagnosed with MND

A teacher who left her job to care for her father after he was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease is launching a charity to help other families.

Alex Gibson's father Guy, 66, from Leek Wootton in Warwickshire, has suffered a rapid decline since doctors confirmed the rare condition in June 2018.

Ms Gibson said she had been shocked by the lack of support for her family.

The 30-year-old has already raised more than £18,000 to help others in their situation.

"I know it's what my dad would do," she said.

Former Massey Ferguson engineer Mr Gibson started noticing changes to his right hand two years ago, after being made redundant and taking up a job as a carer.

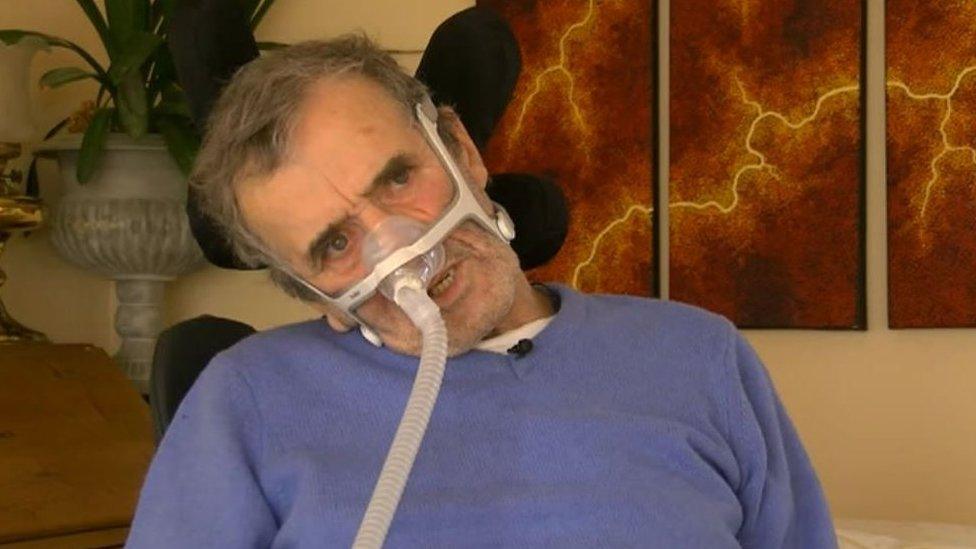

This picture was taken two days before Mr Gibson's diagnosis

"By May 2018 he was sacked from the carer's job because he dropped tea on the floor... and he couldn't put his hand in any of the plastic gloves," said his daughter.

A month later the "tenacious" runner, who had completed a half marathon just six months earlier, was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease (MND).

Ms Gibson clearly remembers the moment she and her brother Jamie were told.

"We were laughing and joking and then my mum said to my dad, 'You need to tell them'. And then he looked at me and my brother and said 'I've got the same as your uncle'," she said.

In a strange coincidence, Mr Gibson's best friend - and his daughter's godfather - had been diagnosed with the disease 18 years earlier.

But her father's decline was much swifter and he went from not being able to clench his right hand to not being able to walk on his own within a month.

What is MND?

It is a group of diseases that affect the nerves (motor neurones) in the brain and spinal cord that tell your muscles what to do

It affects about 5,000 people a year in the UK, according to the Motor Neurone Disease Association (MNDA)

Over time the muscles weaken, stiffen and waste, potentially affecting how sufferers walk, talk, eat, drink and breathe

Symptoms include muscle weakness, cramps and spasms

MND affects everyone differently and symptoms progress at varying speeds, which makes the course of the disease difficult to predict

MND is life-shortening and although there is no cure, symptoms can be managed through physiotherapy, assisted ventilation and medication to help achieve the best possible quality of life.

Ms Gibson left her job as a primary school supply teacher when the family agreed having her father visited twice a day by carers was not sufficient.

She has adapted her father's house for his motorised wheelchair and moved a bedroom downstairs.

Alex posts online about her father's illness, and in this comparison shows his deterioration in a year

But she said she had found the lack of support for the family overwhelming, saying they had turned to the internet to find out how to correctly administer his medication and liquidised food.

"I googled it - honestly it's that awful and I used to think, how is someone not telling me what to do?

"If we weren't involved I can't imagine how it would ever have been ok," she said.

Now Mr Gibson, who can no longer speak, is entitled to two round-the-clock carers, which has eased the pressure on his daughter. But she is never "not on" and slept with her bedroom door open, she said.

"He's gone, he's really not him anymore. He probably is there 1% of the day and that is not even every day.

"I regularly now, without thinking about it, will go up to my dad and put my hand underneath his nose to make sure that he's still breathing," she added.

Mr Gibson's relatives have found there is a large gap in support for family carers

Last November, Ms Gibson started a charitable enterprise called Every Proseccond Counts to help others caring for relatives by holding Prosecco-themed events.

A fundraiser in her local community raised more than £3,000 and since then she has staged a masquerade ball and a football match, with more than three-quarters of profits going to the Motor Neurone Disease Association.

"I feel like it's my happy job, and it makes me feel like I've got a purpose," she said.

She is planning for her social enterprise to become a charity employing staff to visit families after diagnosis.

"I have a loving family, I have the best network of friends ever and yet I still feel lonely... I cannot imagine what it must feel like not to have the support I have and I think that's why I want to be there for other people," she said.

Ms Gibson said, despite the "constant wheel of nightmare," caring for her father was something she would never change.

"The memories I've made with him... no career or relationship would be worth more so I would do it all again even if I lose my marbles," she said.

"It's just so bittersweet because I can still hear when he says I love you, only just, and it's just a grunt, but I can hear it and no one else can."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and sign up for local news updates direct to your phone, external.

- Published1 March 2019

- Published20 April 2018

- Published26 October 2015

- Published1 June 2016