Windscale Piles: Cockcroft's Follies avoided nuclear disaster

- Published

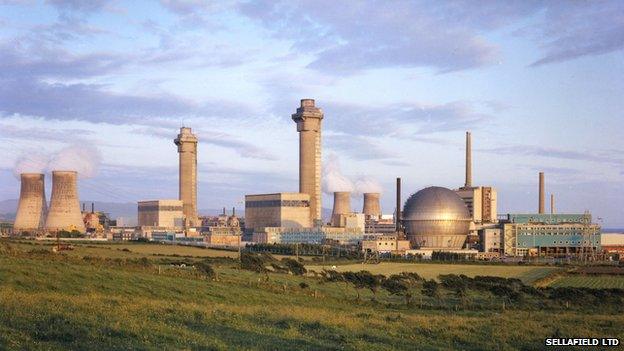

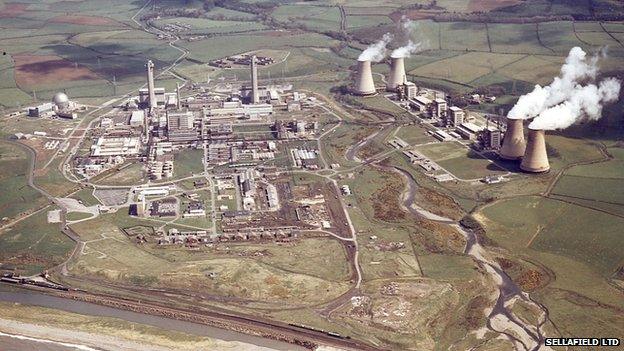

They were labelled a waste of time and money, but in 1957 the bulging tips of two exhaust shafts rising above Sellafield arguably saved much of northern England from becoming a nuclear wasteland. The towers of Windscale Piles have been a landmark for decades but soon the last of these Cold War relics will be gone.

Cumbria's skyline will change with the removal of the towers - known as Cockcroft's Follies - but had they not been in place 57 years ago, the entire landscape may have been drastically different.

Until Chernobyl exploded in 1986, the blaze that ravaged the uranium-fuelled reactor at Windscale Pile One in October 1957 was Europe's most terrible nuclear disaster. It is still the UK's worst atomic incident.

Without the filters - installed at the last minute by Nobel Prize-winning scientist Sir John Cockcroft - the effects of the radioactive dust blasted into the Cumbrian air would have been much more devastating.

"Radioactive dust did escape, but the filters caught about 95 per cent of it," says Christopher Cockcroft, Sir John Cockcroft's son.

"Had the filters not been there I would think a considerable part of the the Lake District and Cumbria would have been put out of bounds, at least for agricultural use and perhaps for people."

Britain's worst nuclear accident

On October 10, 1957, a fire was discovered in reactor one. Uranium fuel cells had ignited with the blaze reaching 1,300 C (2,380 F) and workers battled to stop the whole facility exploding.

Men wearing radiation suits used scaffolding pipes to try and push the burning fuel rods out of the graphite reactor.

The high radiation levels meant they could only spend a few hours at the reactor, more volunteers were sought from a nearby cinema.

Water failed to put out the blaze and the fire was only extinguished when operators closed off the air in the reactor room.

The blaze burnt for three days and significant amounts of radioactive material, most notably iodine-131, were released and spread across the UK and Europe.

It is estimated about 240 cases of cancer were caused by the radioactive leak and all milk produced within 310 square miles (800 square km) of the site was destroyed for a month after the fire.

The level of radioactive material which did escape is estimated to be 1,000 times less than at Chernobyl.

The background to the towers' construction was the rapid escalation of the Cold War's nuclear arms race in the 1950s.

Speed was of the essence in the race to develop nuclear weapons and the UK government wanted to produce weapons-grade plutonium to show it could keep pace with its US allies.

Construction was well under way when Sir John, the director of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment, insisted the filters be installed.

"He saw that if there was a fire, which was probable, there would be no way of stopping radioactive dust escaping into the atmosphere," his son said.

Because they were last-minute additions, the filters were placed atop the two 360ft (110m) tall chimneys rather than at the base.

Sir John Cockcroft received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 along with colleague Ernest Walton for their work on splitting the atom

They were roundly criticised by the engineers building the nuclear facility.

Engineers, who had been told by the government to make the UK a nuclear power by 1952, nicknamed the filters Cockcroft's Follies, mocking them as an expensive piece of pointless delay.

However, as one of Sir John's physicists Terence Price said after the fire, "the word folly did not seem appropriate after the accident".

Professor Richard Wakeford, of the University of Manchester, said the engineers building the plant would have seen Sir John as "sticking his nose in" but he was vindicated in his persistence.

"They did not think there would be a problem, and even after the filters were added I don't think anyone seriously thought there would be a fire, but of course there was," he said.

He said the decision of health chiefs to order the destruction of milk contaminated by radioactive iodine, which has been linked to thyroid cancer, also prevented these cancers.

"They did some quick calculations and ordered the milk produced in a certain area be destroyed," he said.

"It would have been a courageous decision but, ultimately, proved to be right, as it stopped a lot of children consuming the radioactive iodine."

Now the chimneys are being pulled down piece by piece, starting with the distinctive filters. Decommissioning had to wait until radiation levels reached safe quantities.

The first tower was reduced to the same level as neighbouring buildings in 2001, but a higher radiation level in the second has made it much more challenging.

"Dismantling this chimney is one of the most visual demonstrations of the progress we're making to clean up Sellafield," said Tony Price, managing director of Sellafield Ltd.

"Cockcroft's Follies prevented a catastrophe, but the 1957 fire was nevertheless a dark hour for nuclear in the UK and one from which much was learned.

"It is testament to Sir John that the UK nuclear industry is today one of the safest in the world."

Christopher Cockcroft, 72, and his son John visited the site recently to see the final parts of the remaining 530-tonne "folly" being removed.

"We should remember the exemplary courage and devotion of the Windscale men who fought to control the fire back in 1957," he said.

"My grandfather would be extremely proud to know that his legacy of safety in the nuclear industry lives on at Sellafield today."

Related topics

- Published12 June 2014