Why does Alfred Wainwright still loom large over the Lake District?

- Published

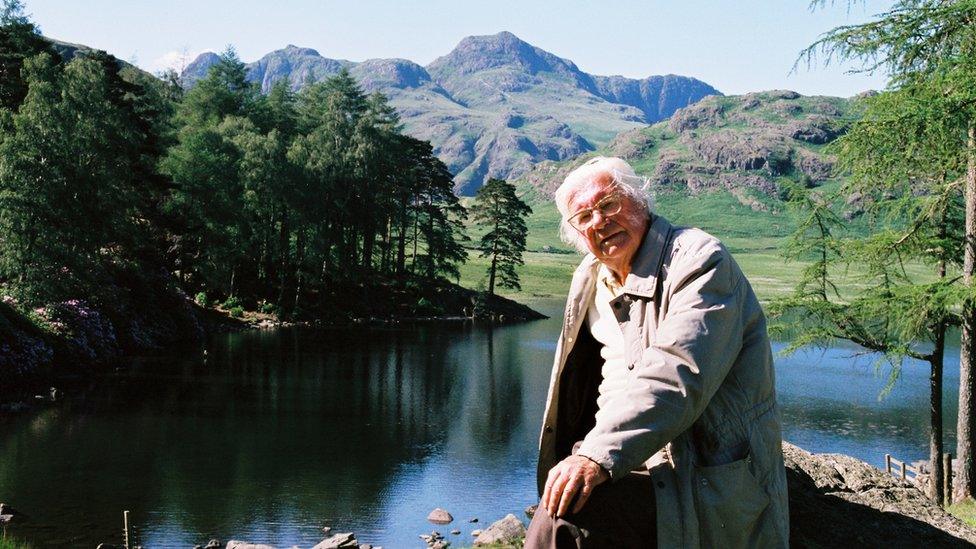

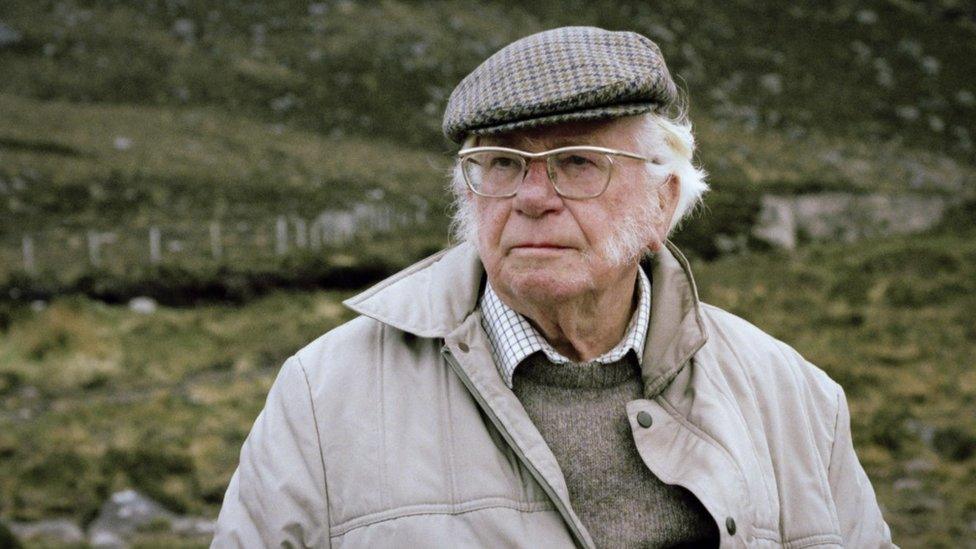

Alfred Wainwright combined much of his writing with his day job as the borough treasurer of Kendal, Cumbria

More than 65 years since his first guidebook was published, and 30 years on from his death, Alfred Wainwright remains synonymous with the Lake District. But why is the connection between the eccentric author and the awe-inspiring landscapes of the fells so enduring?

Donning his flat cap and beige coat, and with tobacco smoke rising gently from a pipe, Alfred Wainwright appeared far from your typical outdoor enthusiast.

Even his behaviour, actively avoiding fellow walkers as he roamed the fells, was at odds with the conventional conduct of hiking.

But having been raised in poverty amid the claustrophobia of Blackburn's cotton mills in the early 20th Century, the lakes and their wide-open vistas provided solace and a sense of wonder that captured his heart.

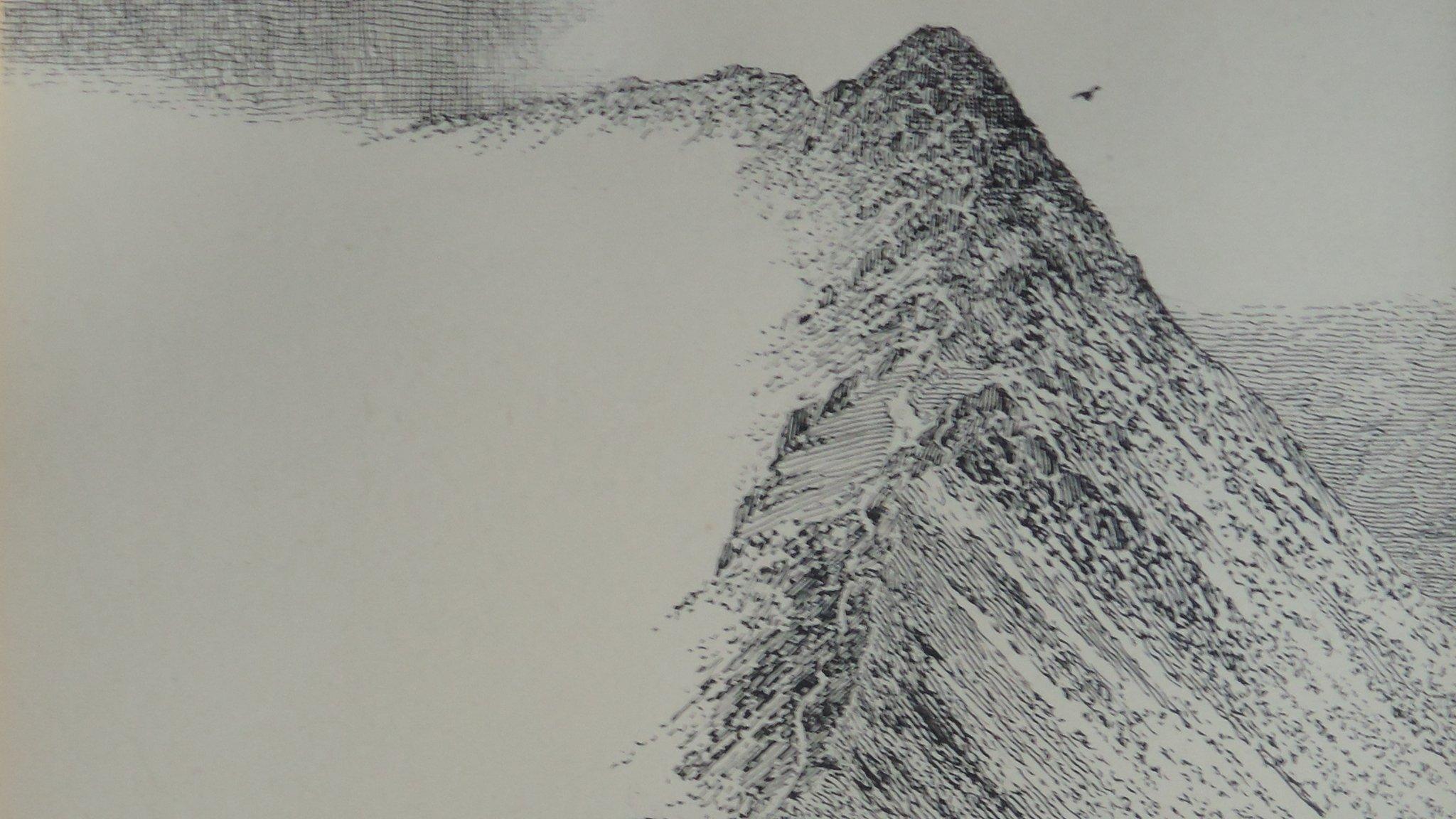

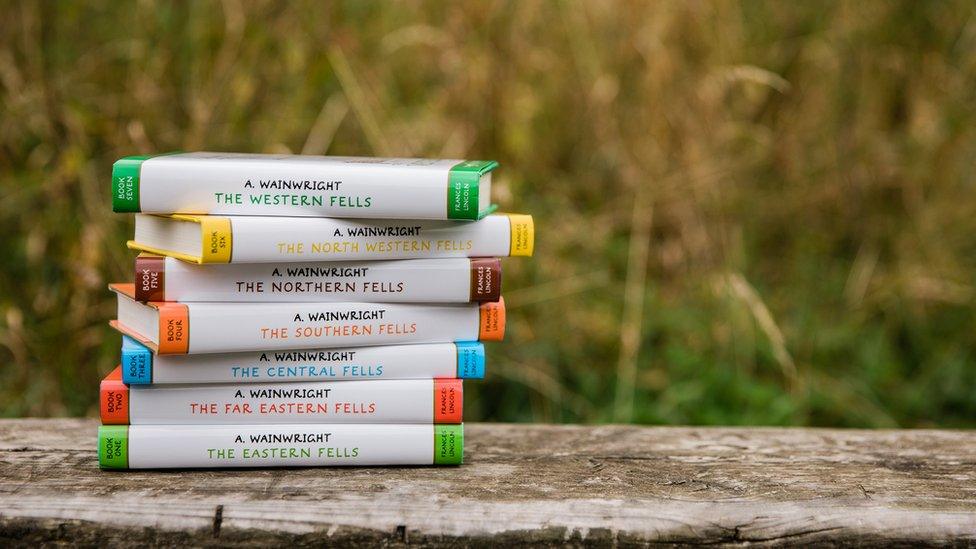

His fastidious pen-line drawings of more than 200 hills and mountains - alongside hand-written descriptions outlining the majesty of each - would stretch across seven volumes of his Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells and sell more than two million copies.

Following years of weekend bus journeys from his then-home in Kendal and fuelled by fish and chips from his favourite haunts, the books were his crowning achievement among the dozens of titles he had published.

Today, in a world increasingly dominated by smartphones and social media, Wainwright's influence is still felt strongly while other writers have fallen by the wayside.

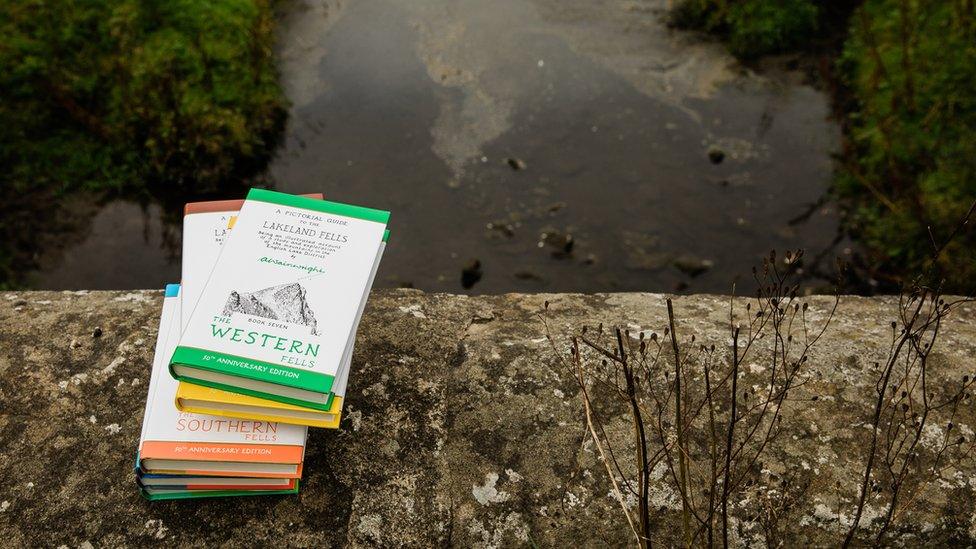

Wainwright's guide books have accompanied generations of walkers on the fells

For biographer and television producer Richard Else, who persuaded the self-confessed recluse to appear on camera in several BBC series during the 1980s, his appeal lies in the scope of the project.

"It was almost a crackpot idea because what he did, in effect, was chronicle every square foot of upland Lakeland.

"People had written books, but nobody had decided to map it out foot by foot, yard by yard. It's a man with a single-minded vision. I can't imagine anyone ever trying to do anything on that scale again.

"I also think they are literary works. He's an extremely good writer. You feel like he's almost walking beside you.

"They're about the history of the Lake District, its ecology, its culture. You can discover the story behind a slate mine or a type of farming. It's the sheer detail."

Wainwright began compiling the first volume in November 1952 with publication following three years later. Dividing the fells into seven areas, the series' final title arrived in 1966.

He combined it throughout with his day job as borough treasurer of Kendal, obsessively spending his evenings writing up notes gleaned from his Saturday and Sunday sojourns.

It was, he told Radio 4's Desert Island Discs in 1988, something he took on "more for my amusement than anything else".

"It ended finally," he went on to say, "with my [first] wife walking out and taking the dog, and I never saw her again."

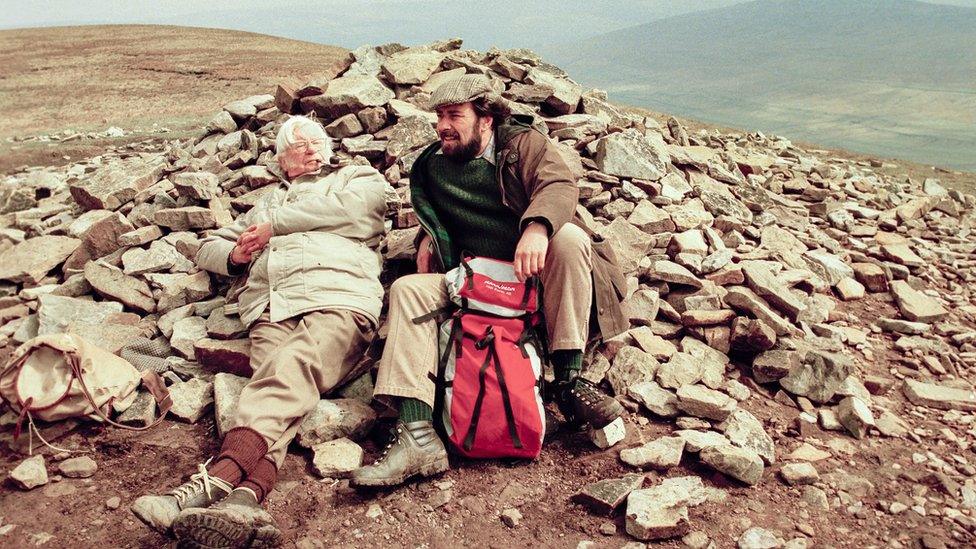

Interviewing Wainwright (left) would prove a tricky proposition for broadcaster Eric Robson

For Else, who will be discussing Wainwright at the Keswick Mountain Festival on 11 September, the chances of getting him on screen had appeared remote.

Indeed, an initial approach for a one-off programme in 1982 was met with a polite rejection.

But as shooting was about to begin word reached him the writer had reconsidered as he thought that without his contribution the show would appear like an obituary.

The TV team soon found Wainwright - or AW as he preferred being called - had a firm vision about how to proceed.

"The very first day we went to his house to film with him, he'd actually planned it in his mind," Else recalls.

"Wainwright said 'I'll sit here, you'll put the camera there and you'll start with the smoke and my chimney and you'll bring the camera down, just like they do in the Westerns, and I'll be here and I'll speak to you'."

Often described as curmudgeonly or difficult, Wainwright himself told Desert Island Discs he was "anti-social and getting worse" with age.

When asked how he responded to walkers he saw on the fells, he replied dryly: "There are boulders you can get behind."

Wainwright's attention to detail was key to the success of his books, TV producer Richard Else believes

Else would forge a strong friendship with Wainwright over nearly a decade as he slowly gained his trust. He remembers well the frequent struggles the production team had persuading him to speak in front of the camera.

Many questions would be met by pauses so lengthy answers looked like they would never come. Often they did not, leading presenter Eric Robson to warn "you'll never, ever make a programme out of this".

Very occasionally, Wainwright, in hushed Lancastrian tones, would unexpectedly talk for half an hour without interruption.

Else, as he first put forward in his 2017 book Wainwright Revealed, believes the writer may have been on the autism spectrum with undiagnosed Asperger's syndrome.

"I don't say that as a negative, but as a positive. I think without that he wouldn't have done the books. They took almost incredible tunnel vision to the exclusion of everything else.

"He also didn't cope with any sort of change easily. We used to go to the Little Chef most Fridays and he'd always have exactly the same meal.

"There was no point asking him what he wanted. It was always fish and chips, a gooseberry pancake and cup of tea. I think he had a genuine fear of things he couldn't control."

The TV programmes proved a surprise hit, eventually appearing among the most-watched on BBC Two with glowing reviews.

"All of a sudden television changed him from being a cult personality to somebody known right across the UK, but celebrity didn't go to his head," Else says.

Wainwright's pen-line drawings have brought more than 200 fells to life for readers

The books' popularity would ebb and flow, and in 2003 they came perilously close to falling out of print before another publisher stepped in.

They have since gone on to find new generations of readers.

Among those spreading the word is Yorkshireman Chris Butterfield, who runs a Wainwright website and Facebook group with thousands of members.

"When I first went to the Lake District 20 years ago, I'd never seen anything like it. I was quite intimidated by the fells, but Wainwright's guides transformed those rugged giants into friendly hills.

"After reading his guides, you view the Lake District in a completely different way. I think that's what captivates everyone. He had a gift very few people have.

"How many guidebooks that are over half a century old are we still reading today? When I'm on the fells, all the guides I see in people's hands are Wainwright's."

Captivated by the "timeless writing", Butterfield has built up a vast archive of material - much of it gathered from printing company Titus Wilson which took over responsibility for the guides from the Westmorland Gazette in the late 1980s.

Describing himself as a "custodian", he is now working on a series of books and plans to stage an exhibition showcasing his many discoveries.

Wainwright and Robson proved popular with viewers of the programmes

"I knew it was a race against time because there are very few people around now who knew Wainwright or were associated with him. In 10 or 20 years' time there would be no chance of doing it.

"I used to visit the [printing] factory every day going through the attics, the cellars, the warehouse, finding all this stuff and original Westmorland Gazette printing materials.

"Months later I'd found nearly all of it. I'd have been happy finding things relating to just a couple of guides, but I found the negatives for all of them and more. It's a colossal amount of material.

"It's been a journey of discovery and a real privilege to protect it all."

So closely connected is AW with the Lake District today, many walkers set themselves the challenge of "bagging" as many of the so-called Wainwrights as they can and his name even lends itself to sporting challenges.

Ultra-runner Sabrina Verjee, who in June set a new record by reaching all 214 peaks in less than six days, says it acts as a kind of shorthand even for visitors who may not be familiar with his life story.

"I talk about the Wainwrights as a set of fells and I would say most walkers and fell runners would know what I mean," explains the athlete, who will be talking alongside Else at the Keswick festival.

"What's nice about the summits is the huge variety. Some are very easy to bag. For example Binsey, you can drive most of the way up on the road and just have a short walk to the top. Then there are more challenging tops like Catstye Cam, which involves a technical rocky ridge."

Sabrina Verjee says she is driven on by the breath-taking scenery charted by Wainwright

With a boom in tourism and an increase in leisure time over recent decades, the Lake District National Park now welcomes 18 million people annually.

Technology, too, has moved on immeasurably since Wainwright died in 1991 at the age of 84.

So what would he make of walkers winding their way across his beloved fells guided by Google Maps and GPS before finishing their adventures with a filtered selfie? And will there still be a place for his printed guides in the years to come?

Else firmly believes there will, but says Wainwright would have viewed the development of technology with "total bewilderment".

"Wainwright retired at the standard age as the borough treasurer of Kendal [in 1967] and he said to me he was so pleased because even the beginnings of computers were beyond him.

"I can imagine telling him you could send a message instantly to somebody and he would say 'what's wrong with the post?'

"He would have seen no point whatsoever in a selfie. He'd have taken a picture of a mountain summit instead.

"Without exaggerating, if you pick out the people whose names would forever be associated with the Lake District, then Wainwright would be in that group.

"I think he'll always have a place because you can genuinely talk about him in the same breath as Wordsworth."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published18 June 2021

- Published25 April 2021

- Published29 June 2020