Polluted legacy: Repairing Britain's damaged landscapes

- Published

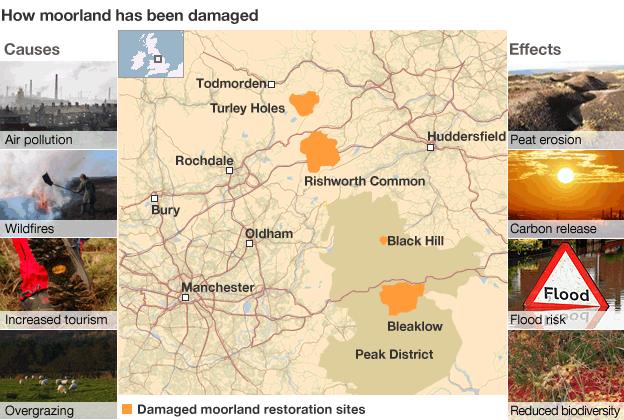

Peat bogs saturated by decades of acid rain erode quickly, especially after moorland fires break out

The Industrial Revolution, which made Britain the powerhouse of the world in the 19th Century, may have been consigned to the history books but it has left a legacy of environmental problems.

Experts warn it continues to pollute drinking water, poison rivers and threaten flooding and in the process it fuels climate change and affects huge swathes of the modern landscape.

The mining of lead, tin and other metals is thought to have contaminated nearly 2,000 miles of waterways. Estimated repair costs run into the hundreds of millions.

Dr Hugh Potter, a mine pollution specialist for the Environment Agency, said: "The metals are going to continue to come out of these mines and spoil heaps for hundreds of years without any significant lowering of the impact.

"So unless we do something about it, it will have an impact for a very long time."

But recent attempts to undo some of this, and other examples of historical damage, have made notable headway.

Fresh research into mine pollution is being carried out, and last year a major project to clean up more than a century of colliery waste in County Durham won international recognition.

And at Bleaklow in the Peak District, efforts to save globally significant peat moorland have reached a crucial stage.

Pollution has made peat there more acidic than lemon juice.

"It was an environmental disaster," said Chris Dean, programme manager of the Moors for the Future partnership, which runs the MoorLife project - set up in 2010 with the aim of repairing 44 sq km of peat moorland affected by 150 years of acid rain.

"Unfortunately for Bleaklow, it was downwind of some of the worst atmospheric pollution the world has ever seen."

Bordered on three sides by the Victorian factories of Lancashire, South Yorkshire and Sheffield - there were 150 industrial chimneys in Oldham alone - it was swept by generations of sulphurous rain.

"This quickly killed off the peat-building moss. And while some other established plants can tolerate the acidity, new plants cannot, so if an area of peat is exposed - say through a fire or shift in the land - it stays open," said Mr Dean.

"If the peat erodes, it flows into the reservoirs where the water companies have to spend more to clean the water. One local treatment plant has just had a £45m upgrade to deal with the problem.

"And moors, because they are so absorbent, act like a sponge with excess water and can be very effective at preventing flooding."

Peat moorland is also the single biggest store of atmospheric carbon in the UK. If allowed to erode, the carbon is released into the air as carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas.

Mr Dean added: "The blanket bogs are still in intensive care. Some areas are too badly damaged to return to a pristine condition but huge progress has been made and we will be able to turn areas into something much more biodiverse and much more efficient at providing those eco-system services we need."

The Moors for the Future project can draw encouragement from the Durham Heritage Coast.

These images show the transition of Dawdon (top) and Easington (bottom) from working collieries to industrial tips, and finally heritage coastline

From the mid 19th Century, six collieries between Wearside and Hartlepool dumped up to 2.5m tonnes of mine waste a year on to the shoreline.

In places the spoil was 10 metres (33ft) thick, with the affected zone reaching as much as 7km (4.3 miles) into the sea.

Niall Benson, an officer with Durham Heritage Coast, said: "It was just trashed, to be honest.

"A report by divers into marine life in 1992 basically said 'It's black, we can't see our hands in front of our faces and there is nothing on the sea bed'.

"The pit heaps smothered everything they were on and made much of the ground acidic."

From 1997 to 2002, the Turning the Tide partnership spent £10m regenerating the area.

More than 1.3m tonnes of spoil was removed and 80 hectares (198 acres) of land reclaimed from pit sites, with another 225 hectares (556 acres) nearby replanted.

Mr Benson said: "The closing of the pits caused a lot of pain but there is a recognition that the project brought opportunities and a quality of life to the area.

Blackhall beach, location for the finale of thriller Get Carter, is at the heart of the heritage coast

"It has given the coast back to the people who live there, given them a sense of ownership, but also opened it up to visitors from everywhere else."

A number of Sites of Special Scientific Interest and nature reserves have since been established in the area, notable for its rare limestone grassland.

While the heritage coast is a success story, efforts to deal with a less obvious, but more widespread, kind of mining pollution, have just begun.

Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) occurs when abandoned pits and slagheaps flood, overflow and contaminate rivers and soils.

Mines abandoned before 1999 carry no legal decontamination obligation and while old coal mines are dealt with by the Coal Authority, efforts to clean up non-coal mines, mainly in the Pennines, Cornwall and Wales, have so far been piecemeal.

About 400 of the UK's waterways - roughly 3,000km (1,864 miles) in total length - are thought to be affected by substances like cadmium, zinc, lead and arsenic.

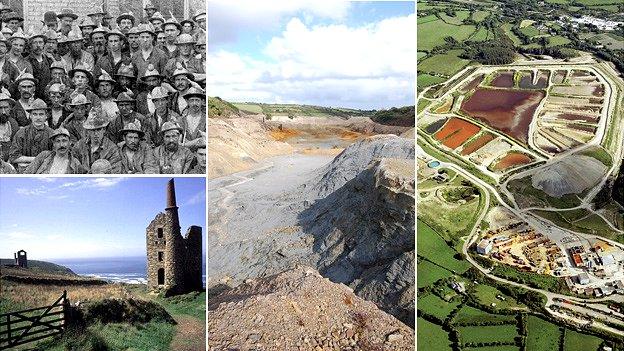

Centuries of mining left much of Cornwall's landscape altered both visually and chemically, with some areas desolate and others needing treatment to clean the water

Although the risks to drinking water are deemed to be low because humans are relatively tolerant of this type of pollution, some rivers have been stripped of aquatic life.

Researchers still have a long way to go to understanding the effects on the wider food chain.

In Cornwall, the problem is far-reaching and expensive. A water treatment plant set up at the former Wheal Jane tin mine, following the contamination of Falmouth Bay in 1992, has so far cost £20m.

Nearby Wheal Maid mine has been fenced off, deemed too hazardous for human activity.

Arsenic concentrations in gardens in Camborne <link> <caption>have been measured at 320mg per kg</caption> <url href="http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/static/documents/Research/SCHO0409BPVY-e-e.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> , against a UK average of 10.9 and an Environment Agency guideline of 32.

There are thought to be about 2,000 old mines in Cornwall alone, meaning hundreds of acres in the county, both rural and developed, are affected.

Many old metal mine sites are now listed, limiting the ways acid mine drainage can be dealt with

Nationally, the scale of the situation is only now being defined, with a recent estimate suggesting the cost of treatment could be £400m over 10 years.

With an eye on cost, research is focused on low-maintenance wetland style filtration.

Dr Potter said: "We are working out where exactly in the river catchments the pollution is coming from. We will then look at what we can feasibly do to clean that up.

"It's going to be a long programme, there are a lot of problems and limited resources, so we are chipping away."

So profound has the impact of pollution been on some landscapes that they have given rise to unusual mixes of plants and wildlife - now officially protected in their current state.

Lead mine spoil heaps often support a rare type of grassland dominated by spring sandwort and sheep's fescue.

In Cornwall, it has led to an unusual mix of coastal and heath plants, especially moss and liverwort populations, including the only site in the world for Cornish path moss - at Phoenix United Mine.

"It makes for an interesting extra discussion when looking for a solution," said Dr Potter. "We have to find a balance."

<italic>Photos: large image 1, clockwise from left; Picture Sheffield, Getty Images, Moors for the Future, BBC</italic>

<italic>Large image 2, clockwise from top left; Coal Authority, Durham County Council, Darren Wilkinson, Visit Durham, Mike Jones, Durham County Council</italic>

<italic>Large image 3, clockwise from top left; JC Burrow, Dave Johnston, Environment Agency, BBC</italic>

- Published12 June 2012

- Published29 May 2012

- Published16 December 2011

- Published20 October 2011

- Published15 September 2011

- Published30 August 2011