Don Hale: One man's fight for justice

- Published

Don Hale has helped to clear Barry George, Stephen Downing and Ched Evans

Fifteen years ago Stephen Downing was acquitted after spending 27 years in prison for murder, overturning one of Britain's most notorious miscarriages of justice and putting into the spotlight the local newspaper editor who helped to bring the police's case tumbling down.

Don Hale could hardly have foreseen that by championing the case he would go on to suffer police intimidation and receive death threats - there were even two apparent attempts on his life - forcing him to leave his Derbyshire home.

But the Downing case would eventually change the law, win Hale an OBE and make him a go-to journalist to investigate major miscarriages of justice.

In the years since the release of Mr Downing, Hale has also helped to free Barry George, the man who spent eight years in jail for the murder of Jill Dando, and to clear the name of footballer, Ched Evans, after a controversial rape retrial.

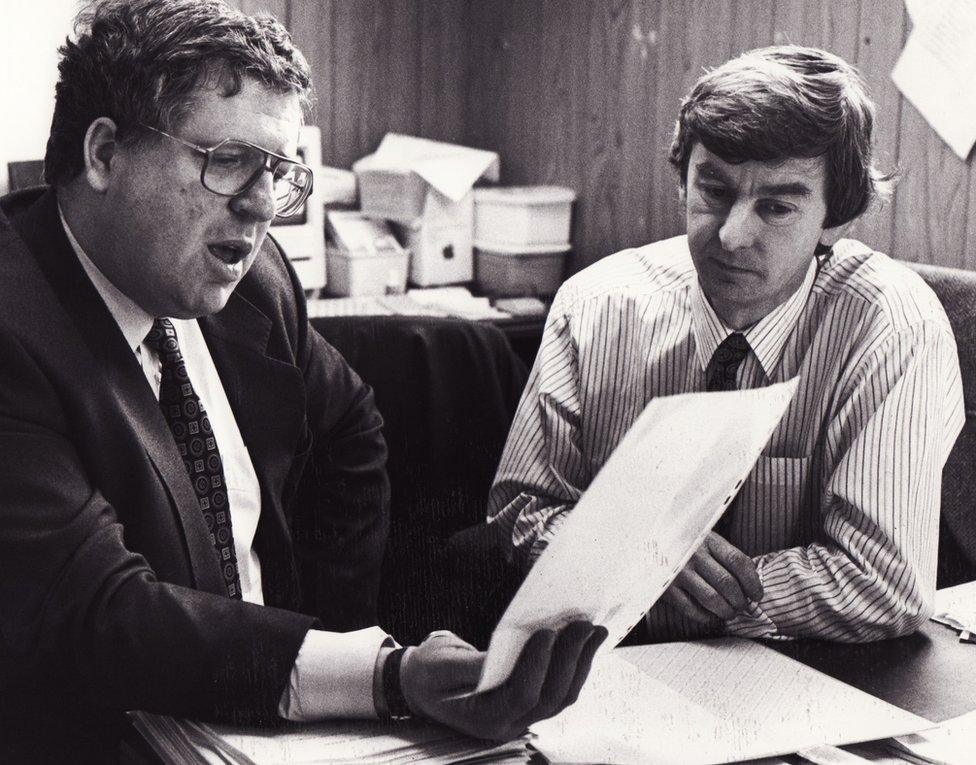

Don Hale was editor of weekly local newspaper, the Matlock Mercury, during his battle to free Stephen Downing

For Hale, the brutal trigger for his life of campaigning was the 1973 killing of 32-year-old Wendy Sewell.

She was found badly beaten but still alive in a Bakewell graveyard by Mr Downing, a council gardener.

He was arrested and questioned without a solicitor for several hours but, aged 17 and with a reading age of 11, officers pressured him into signing a confession to the attack, filled with words he did not understand.

When Mrs Sewell died two days later, the charge was upgraded to murder. Mr Downing immediately retracted his confession but was found guilty at a trial at Nottingham Crown Court.

Legal secretary Wendy Sewell, dubbed "the Bakewell Tart" in the press, was left for dead in the cemetery

After their son had spent two decades in prison, Mr Downing's parents approached Hale, editor of the Matlock Mercury, for help.

He faced obstacles at every turn, with police telling him all the evidence had been "burnt, lost and destroyed".

A turning point came when Derby Museum staff informed him that the murder weapon - a pickaxe handle - was on display there.

With Hale's help, Mr Downing won £13,000 from the Legal Aid Board.

This paid for a modern forensic examination of the weapon, crucially revealing Mr Downing's fingerprints were not present - although there was a bloody palm print from an unknown person.

The clothes Mr Downing had been wearing, which had been returned to his parents, were flecked with spots of blood which Hale believed were consistent with him having tried to help Wendy Sewell as she lay dying.

Twenty years after the murder Hale reshot scene of crime photographs in Bakewell cemetery

"I reported developments through the Matlock Mercury - it became like The Archers, a bit of a saga," he joked.

But the articles prompted real-life drama in the form of anonymous death threats and what Hale claims was police harassment.

"They made my life absolute hell for five or six years," he said.

"I was pulled up for speeding, stopped and searched, victimised."

Letters were sent to his home and a brick was thrown through the newspaper's window.

Most seriously, on two occasions a vehicle was driven at him at speed, which he believes were attempts to kill him.

Police even gave him a mirror on a stick to check for bombs under his car.

Don Hale marching for justice for Stephen Downing

"I was very worried for my family. There weren't threats against other journalists, it was simply against me. It turned into a rollercoaster," he said.

But all of this merely strengthened his resolve: "If Downing had done it, why should anyone want to threaten me?"

Mr Downing was ineligible for parole under the law at the time because he had refused to admit his guilt.

Hale believed this was unfair and took the matter to the European Court of Human Rights, winning the case in 1996.

It was adopted into law that prisoners who maintained their innocence after conviction could apply for parole.

Derbyshire Dales MP Patrick McLoughlin became one of the Downing campaign's high-profile supporters

By now, the Downing case was attracting attention from far and wide: "I became a hero in Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Argentina, because I had taken on the British government and won," Hale said.

Closer to home, Hale said then Prime Minister Tony Blair asked him for help in setting up an independent body to investigate miscarriages of justice, which became the Criminal Case Review Commission (CCRC).

Stephen Downing's was one of the first cases to be looked at by the CCRC.

It recommended his conviction should be overturned on the basis that the circumstances in which he gave his confession made it unreliable evidence that should not have gone before a jury.

The conviction was quashed in 2001 with Mr Downing finally walking free in January 2002.

Hale and Stephen Downing on the steps of the Royal Courts of Justice in January, 2002, after his conviction was overturned

Hale was pleased but also disappointed: "He had got off on a technicality," he said.

"He didn't get his day in court because police were bang to rights. Somebody should have been called to account."

The legal challenge to Mr Downing's conviction focused on the way detectives had conducted the original investigation in 1973.

He had been questioned without a lawyer and there were serious doubts about whether he had been properly advised of his legal rights.

These facts were never made known to the jury that convicted him, but they were enough to overturn the conviction.

But Mr Downing, for his part, was not angry: "Who would I feel bitter against? The system? I think I would be punishing myself," he said.

With much more to say himself, Hale wrote the book, Town Without Pity, which was turned into BBC drama, In Denial of Murder, in 2004.

In Denial of Murder starred Stephen Tompkinson as Don Hale and Jason Watkins as Stephen Downing

Police reopened their investigation, interviewing 1,600 witnesses, at an estimated cost of £500,000, but failed to identify any alternative suspect - although Hale has previously said he believes he has a "very good idea", external who killed Wendy Sewell.

Mr Downing was later awarded £900,000 in compensation.

The huge press attention the case attracted finally forced Hale to relocate to north Wales.

"One of the reasons I moved away from Derbyshire was to get relief," he said. "It wasn't fair on my family."

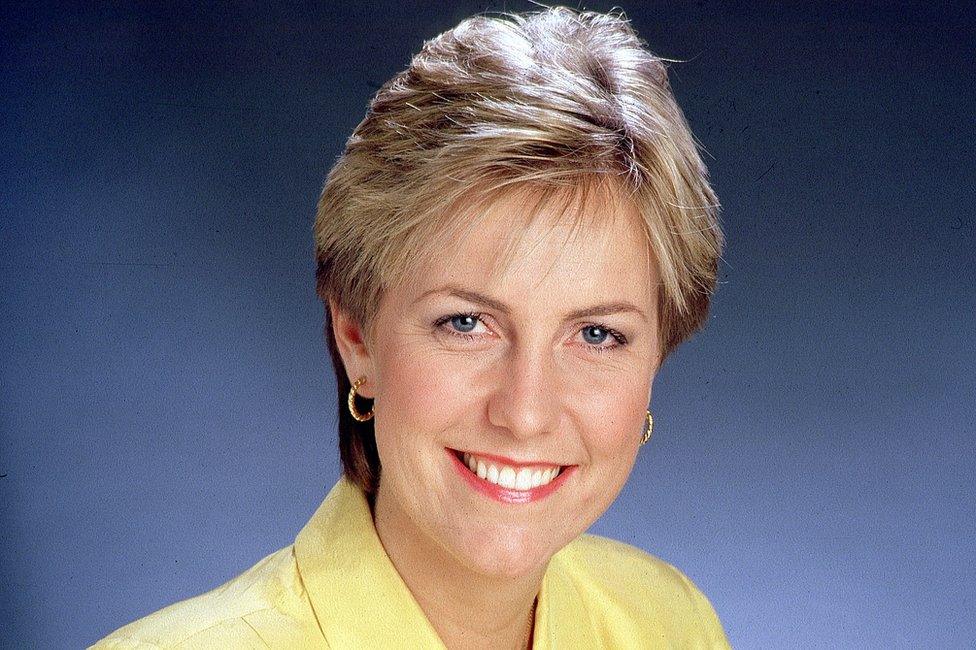

Jill Dando's killer has never been brought to justice

But he was soon called on to help with another miscarriage of justice.

BBC Crimewatch presenter Jill Dando was shot dead on her fiancé's west London doorstep in April 1999.

A year later, after interviewing over hundreds of people, the Met Police charged 41-year-old Barry George, a self-confessed stalker and loner, with her murder. He was tried, convicted and jailed for life.

But there were serious concerns about the police investigation, and in 2004 Hale was asked to get involved.

"Quite quickly, I found a lot of evidence that didn't match up," he said.

Barry George was "an oddball but not a killer", Hale said

He went to see Mr George in prison where he was "like a lion in a cage", pacing the floor.

"How could he do a clinical murder like that?" Hale said.

"Everyone that was dealing with him said he's a bit of an oddball but he's not a killer."

Gunpowder residue on Mr George's clothing had played a large part in convicting him.

But Hale said there was so little of it that it could have come from weapons armed police were carrying when he was arrested.

The CCRC referred Mr George's case to the Court of Appeal and a retrial took place at the Old Bailey in 2008, when he was cleared of murder and released.

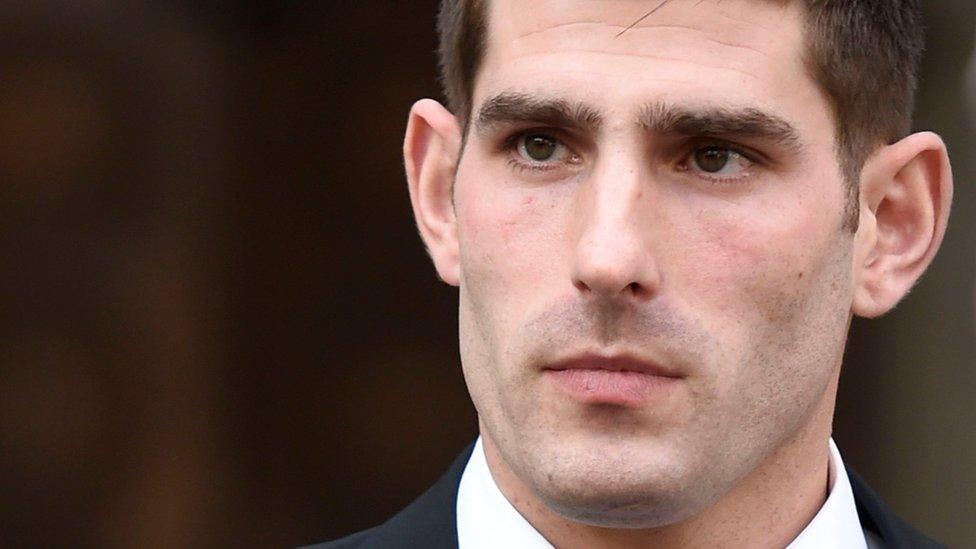

Ched Evans leaving Cardiff Crown Court with his fiancee Natasha Massey

Ched Evans was serving a five-year sentence for rape when his family approached Hale for help.

"I didn't want to touch it because it was so high profile," he said.

But Mr Evans' mother had serious doubts about the "rushed" investigation.

The then-Sheffield United striker had been convicted of raping a 19-year-old woman at a Premier Inn in Denbighshire in May 2011.

At the same trial, footballer Clayton McDonald was acquitted of the offence.

Hale believed the guilty verdict was an "emotional response" from the jury, owing to Mr Evans' "cockiness". "He thought he was God's gift to women," Hale said.

He spent six months working on the case, in which time Mr Evans was released having served half of his sentence.

"My knowledge and experience meant I could cut corners and had an important point that I knew the IPCC would look at."

A timeline of events leading to Ched Evans clearing his name

That point was the woman's sexual history and, after the CCRC agreed there was enough evidence to quash the conviction, this evidence controversially formed part of the retrial.

Unlike during the original trial, her previous sexual partners gave evidence recounting similar encounters to the one in the hotel room that night.

It led to plans to review the law protecting alleged rape victims from disclosing details of their sex lives.

Mr Evans was cleared in October 2016 but it left a bitter taste for Hale.

"In this case it was right - you have got to look at each case on its own merit," he said.

"But the whole thing was a bit unsavoury and not good for the girl herself."

Hale said at the time he hoped the case did not deter women from coming forward to report sexual offences.

But, had that evidence been used in the original trial, "Evans would have been cleared," he said.

The case took its toll on Hales, now 64, and he has decided not to investigate any more miscarriages of justice, focusing instead on writing books.

"I am proud of what I have done," he said.

"If it wasn't for people like me you'd have no-one to say, 'this isn't the way we should interview people, this is not the way we should treat people'."

Yet he still insists modestly that much of the credit for overturning the miscarriages of justice he has worked on belongs to others, seeing himself more as a catalyst for change.

"You have got to have somebody who gets the ball rolling."

- Published15 January 2014

- Published15 October 2016

- Published27 October 2016