Enigma code veteran to take secrets 'to end of my days'

- Published

Codebreaker, 95, still keeping Bletchley secrets

A World War Two codebreaker has vowed to take the secrets of her work "to the end of my days".

Margaret Wilson, 95, trained as a wireless operator before being transferred to Bletchley Park in 1942, where she listened to German radio.

"That's all I can tell you, a secret is a secret," she said.

At the time, she did not realise the importance of the work - but even now she knows its significance she will not reveal all.

Despite pleas from researchers and family, Mrs Wilson, from Shirebrook, said: "No one else has talked, so I will not."

She joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force, aged 19. After some months she was told to sign the Official Secrets Act and sworn to lifelong secrecy by a Justice of the Peace.

She was then told she was off to somewhere called "Bletchley".

"I had never heard of it," Mrs Wilson said.

First impressions were not good. Driven to work in a car with "awful" blacked out windows, the sergeant in charge was a "miserable git".

Margaret Wilson laid a wreath at the cenotaph in London

Working from a wooden hut, Mrs Wilson was part of a small team that recorded German radio transmissions, 24 hours a day.

Their focus was the dots and dashes of Morse code messages, which had to be picked out from the jumble of other noises and voices in the broadcasts.

Mrs Wilson said: "You did this all day, it never stopped, for eight hours.

"And you never spoke to the other girls - who were not sat far away - not 'yes' or 'no' or 'how are you', nothing.

"When you wanted to go to the toilet, you had to put your hand up and the sergeant would sit down and do your work.

"And in the night that happened more because you went to wash your face to wake up."

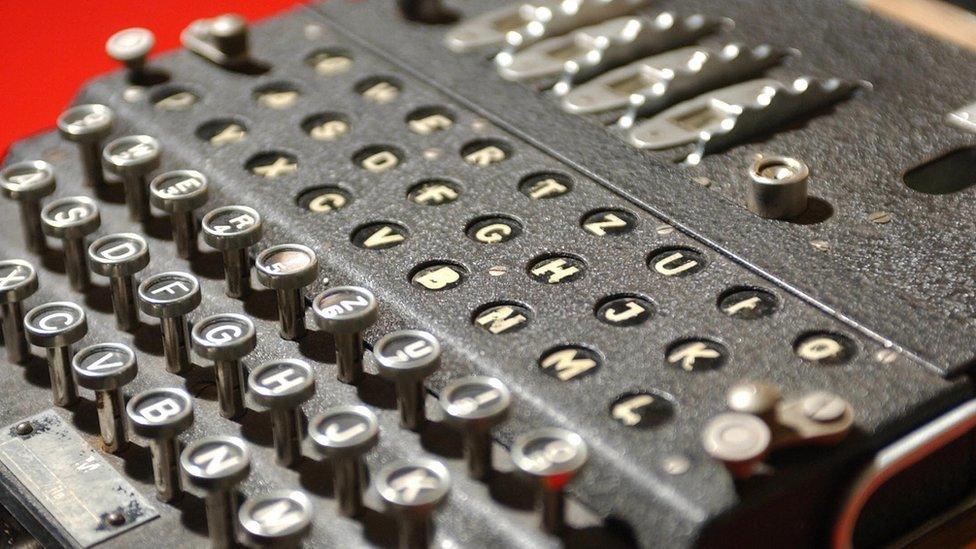

German forces used the Enigma machine to encrypt their messages

They were told nothing of who, what or why behind the work - but soon picked up a hint of the challenge.

"Important messages came in five-letter groups - those were the ones which got sent off quickest - but that's all I can say," she said.

Mrs Wilson left in 1946 but stuck to her oath of secrecy, telling neither her husband or her children about it.

It was only in 2013 when official thanks were sent to those who worked at Bletchley that part of the story come out.

She then returned to Bletchley, now a museum, and "within minutes I was surrounded by bigwigs".

"They say 'Margaret, you can tell us' and I say, 'You were not the one sworn to secrecy and told never, ever to disclose it to the end of your days'," she said.

"The JP said, 'They will try to get it out of you, they will tell you it is fine but don't tell', and that for me is the end of it."

She says her "one regret" is not telling her late husband about her work.

"I didn't see any point in [telling him about it], it didn't mean anything. It's only just recently it's been brought out how secret it was," she said.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published8 March 2018

- Published17 January 2017

- Published3 October 2013