Covid: Prison outbreaks thought to skew stats

- Published

A number of rural areas have found themselves at the top of the coronavirus infection rate table because of prison outbreaks

Coronavirus outbreaks in prisons across England are believed to lie behind several regions' spikes in infection rates, causing "a degree of alarm" according to health officials.

This is despite cases nationally reaching their lowest point since September 2020.

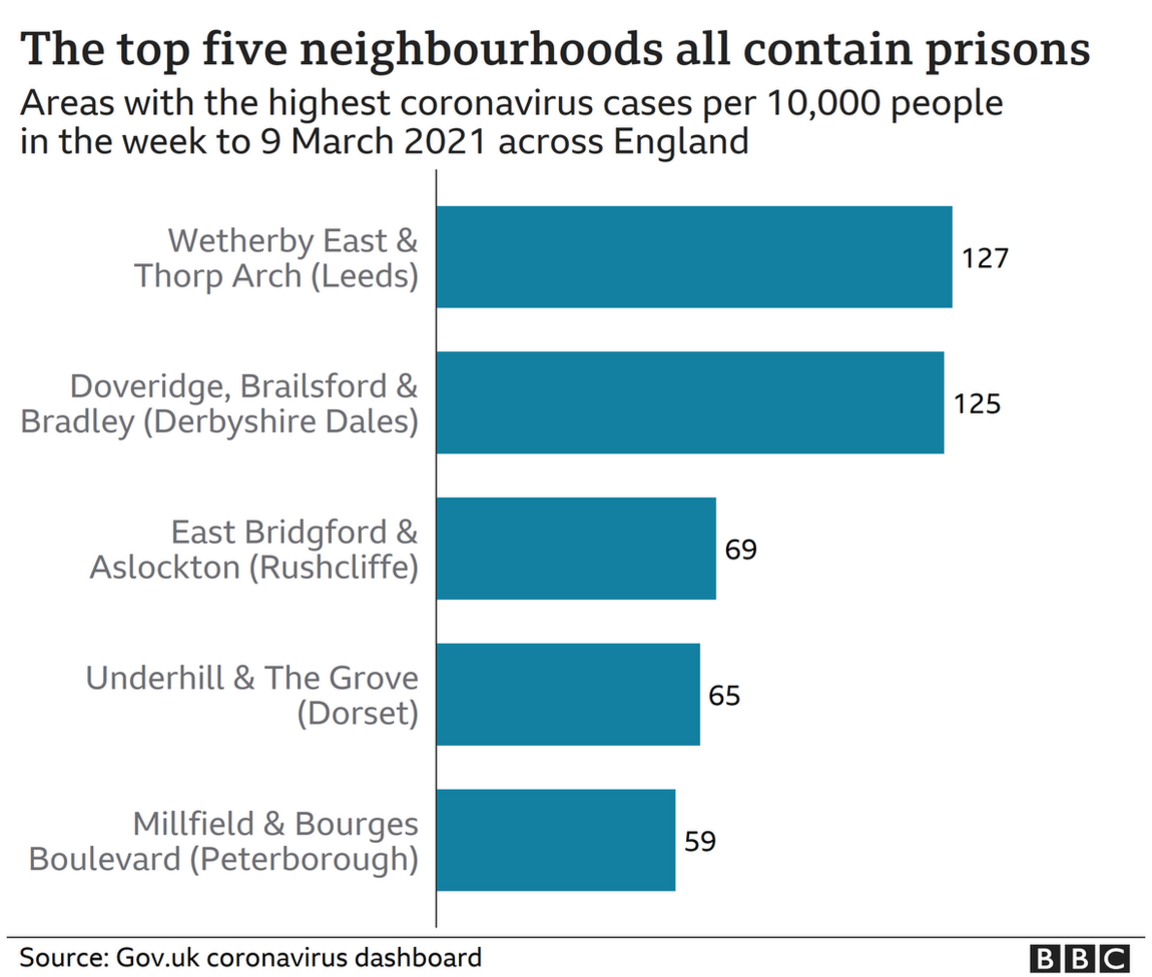

BBC analysis of neighbourhood-level data found five of the places to have recorded the highest infection rates in the country recently all contained prisons.

The Ministry of Justice has said there is no evidence to suggest prison outbreaks have affected transmission in the wider community.

But have these cases been skewing the overall figures in some areas?

Which areas have seen spikes recently?

An outbreak at HMP Sudbury in early March caused cases in the Derbyshire Dales to nearly treble, pushing the area to record the highest infection rate in the country for several days.

Similarly, a surge in cases across half of the 12 male wings of HMP Peterborough in late February happened while the area's rate reached the second highest in the country.

Earlier in February, an outbreak at HMP Stocken in Rutland caused the infection rate in England's smallest county almost to double, with officials saying at one point "around half" of cases in the area were from the prison.

An outbreak at HMP Sudbury sent Derbyshire Dales to the top of the coronavirus infection rate table

What does the data show?

Looking at government data showing coronavirus cases in smaller areas within local authorities, places with prisons recently ranked highly compared with other parts of England.

In a snapshot taken for the week to 9 March, the five areas with the highest infection rates in England had included seven prisons, of which at least five reported outbreaks in the past few weeks.

However, it is possible additional cases from outside prisons may be adding to the rate for these areas.

What is the situation like inside prisons?

"This has been the toughest year," said Mark Fairhurst, national chairman of the Prison Officers' Association and himself a prison officer in HMP Liverpool.

According to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), 86 prisoners had died in England and Wales with Covid-19, until January.

The deaths have been absolutely horrendous... prisons are impossible to socially distance in

Mr Fairhurst said 30 of his colleagues across the country had also died since the pandemic began.

He said there had been outbreaks in 94 out of a total of 117 prisons at one point last month.

"The deaths have been absolutely horrendous," he said.

"Prisons are impossible to socially distance in.

"They're a confined space and any virus or disease spreads rapidly."

Mr Fairhurst said the pandemic had highlighted how "brave" and "essential" prison officers are

But he said prison staff had been "doing their best" and as a result had "actually saved lives" as the death toll is far below Public Health England's projected 2,300 prison deaths in March 2020.

"I'd just like the public to recognise prison officers for the role they do, keeping the public safe," he added.

An MoJ spokesperson said the "tireless work" of prison staff, along with testing, had saved lives.

They added they had "robust safeguards to stop the spread of coronavirus".

An inspection at HMP Leicester criticised conditions but said staff had done well to limit the number of cases

But those measures had come at a "heavy cost" for prisoners, according to a report by HM Inspectorate of Prisons, external.

Inspectors found that at the start of the pandemic, prisoners across England and Wales spent all but 45 minutes locked in their cells every day.

Even when lockdown was eased over summer, inmates were still only allowed out for an average of 90 minutes a day.

One inspection at HMP Leicester found prisoners were living in dirty and cramped cells, unable to shower every day, but said staff had done well to limit cases.

Across the country, activities such as work, education, rehabilitation and visiting the library were stopped.

One female prisoner told inspectors: "Your room is tiny… and you're in that room 24/7, you've had your dinner in there, you've slept in there, you've done everything in there. Those same four walls, it's just demotivating."

Inspectors said rehabilitation had suffered and this could leave the public more at risk when prisoners were released

Peter Dawson, director of the Prison Reform Trust, said: "Prisons are currently only containing the virus by imposing exceptionally harsh restrictions on prisoners.

"But even that cannot stop infection taking hold in overcrowded conditions and buildings that are often cramped and dilapidated."

He urged ministers to release low-risk prisoners to ease pressure and to vaccinate inmates and staff.

Are outbreaks in prison a risk to wider populations?

The simple answer is that prisons are unlikely to present a risk.

Mike Sandys, director of public health in Leicestershire, dealt with Rutland's own rise to the top of the table.

He said prisons inform Public Health England when they have an outbreak (classed as two or more linked cases), who then pass the information on to local teams.

This meant he was aware of the problem and already working with HMP Stocken days before the news broke that Rutland had the worst rates in the country.

He said: "I got a few panicky calls from [central government] that morning. Someone woke up and thought, what is going on in Rutland?

"But they were easy ones to answer.

"It does provide a bit more heat from the centre and when the public see the figures... it does cause a degree of alarm."

Mike Sandys said, particularly when case rates are low, an outbreak in a prison can send an area "hurtling" up the table

But he said prisons were "enclosed" populations, making the virus easier to track than a community or workplace outbreak.

He added residents in such areas should not worry but, equally, they should not be complacent.

According to the MoJ, there is "absolutely no evidence" an outbreak in a prison has led to a significant rise in cases beyond its walls.

WORLD LOOK-UP: Where in the world are cases highest?

TESTING: What tests are available?

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk.

- Published11 February 2021