WW1's fighting footballers: Exeter City players go to war

- Published

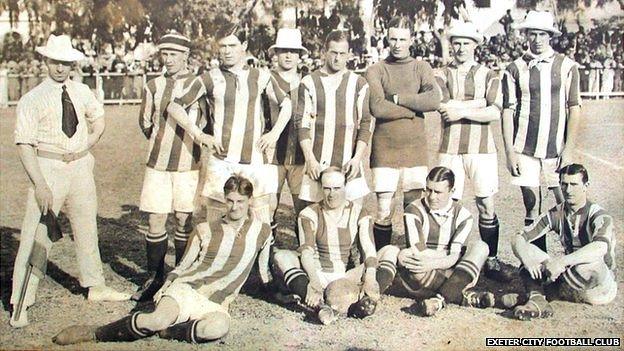

The 15 players on the tour signed up for the army or took jobs in armament factories

On 4 August 1914 as Britain declared war on Germany, an English football team was in the middle of its return voyage from a tour of South America. Their journey back would involve narrow misses with warships - and their lives as footballers would never be the same again.

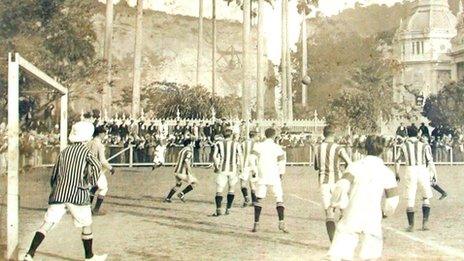

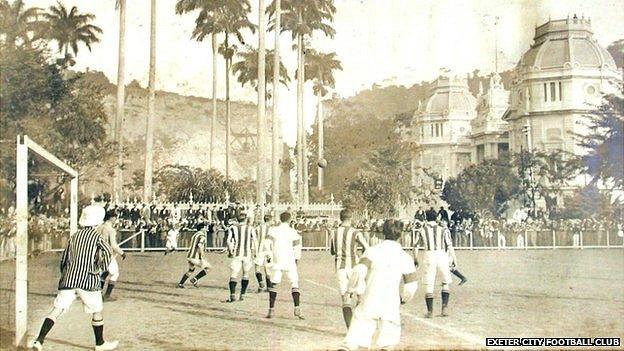

The 15 players in Exeter City's touring squad were on their way back from a tour of Argentina and Brazil, during which they suffered a 2-0 defeat to the first-ever Brazilian national team, when news reached them about discord back in Europe.

The assassination of Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand was escalating into something that would become known as World War One.

"The news of declaration of war between Germany and France caused great excitement between the mixed body of passengers," wrote club chairman Michael McGahey in a letter published by the Exeter Express and Echo newspaper shortly after the team's return.

"[At] about 12 midnight when the wireless message was received as to the declaration of war between England and Germany... the news had the most sobering effect.

"Everybody felt the world was fated with a terrible ordeal, the end of which no man could foresee."

Alone on the ocean, the fate of the ship, its passengers and crew depended on which nations' ships they encounter first. If it was an enemy nation those on board, especially young fit men of military age, could spend the war in internment camps.

Mr McGahey said it was a "startling adventure" as the team's ship was twice fired on by warships - once near the English Channel - as they put warning shots across its bow.

The club agreed to the trip to Brazil after Nottingham Forest and Southampton turned down the opportunity

Luckily for the players, on both occasions the ships were French - Britain's allies. The ship was allowed to continue its journey although the crew had been told to stay away from Southampton and landed in Liverpool instead.

'Up-and-coming team'

Mr McGahey said as the players headed back to Exeter by train, "they were looking forward to the start of the 1914-1915 season, which was in a few days' time".

But life would prove not to be that simple.

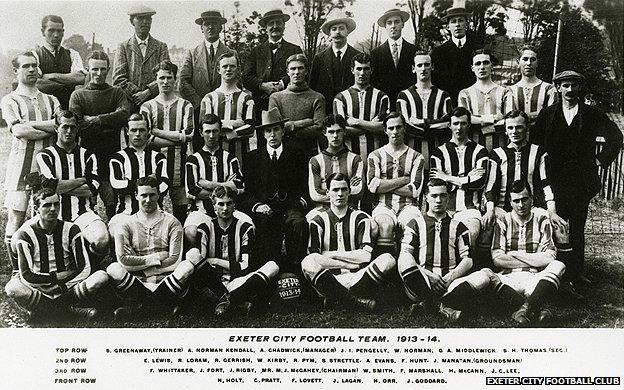

At the time, Exeter played in the Southern League, alongside Reading, West Ham, QPR and Norwich, and were seen as a team with lots of potential.

"They were an up-and-coming team, including two people who later played for England," says Alison Styles, who is related to one of the players, Jimmy Rigby, and now researches the wartime lives of the Exeter City players.

"They were poorly paid but they were as professional as Manchester United and Liverpool at the time."

Once back in Exeter, the players turned out for a couple of pre-season matches and the gate money from those was donated to the War Relief Fund.

But in the meantime, some of the club's amateur players who were army reservists had already been called up. Others answered the call to volunteer.

Among those first to the colours were amateur players George White, the club's captain for the 1913-14 season, who joined the 1st Devon Regiment in August 1914, and Fred Bailey who joined the 1st Wessex Divisional Field Ambulance in November.

In October 1914 White became the first Exeter City footballer to die in the war.

Amateur player Fred Bailey died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916

"George White had actually come into the hospital where Fred Bailey had been working and died there," said Aidan Hamilton, the author of Have You Ever Played Brazil?, which he wrote about the South American tour, the wartime exploits of the players and their post-war football careers.

The following year Bailey suffered a gunshot wound during battle and had to be operated on.

He recovered, but later was killed as one of the 60,000 British casualties on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

"It's just a snapshot of the horrors of war and the fine line between death, between people who died and people who survived," said Mr Hamilton.

'Need more men'

The historian said the war by this point had already started to have an impact on football as some of the early matches were used to shame fans into signing up to military service.

Professional players had to get permission from their club to sign up or it would break their contracts

"Photos of the crowds of the football matches were used to show those in civilian clothes next to those in khaki uniform," said Mr Hamilton.

"[They were] under headlines like, 'We need more men', saying to civilians, 'if you're standing next to someone in khaki aren't you ashamed?'."

As reports of casualties started coming in from France, the focus moved from those in the crowd to those on the pitch.

"A lot of people were very, very anti-football because they were seen to be fit young men running around pitches when they should be fighting," said Ms Styles.

This anti-football movement led to the suspension of the professional football leagues in July 1915 for the duration of the war.

The grandstand of Exeter's ground St James Park became a barracks, housing a regiment and the pitch was used as a rifle shooting range.

Before the suspension of the leagues, professional players had been unable to volunteer without their club's consent as this would break their contracts.

And until conscription was introduced in January 1916, it was still up to individuals whether to volunteer or not.

"By the beginning of September 1915 a local football correspondent says that the vast majority of players connected with Exeter City had joined the colours," said Mr Hamilton.

Winger Fred Goodwin is thought to have been the first of the 15 players who toured South America to sign up for service.

He joined the 17th Middlesex Regiment, one of two known as the Footballers' Battalion. Having previously served in the military, he was employed as a bomb-throwing instructor.

'The shooting stopped'

During the war he was seriously wounded and never played again.

His teammate Billy Smith's career ended, meanwhile, when he lost a leg.

The half back had been a successful player and, while serving in the military, had agreed a post-war move to Everton. However, he was shot on 12 November 1918 - a day after the armistice had come into force.

The wound led to his leg being amputated in a Liverpool hospital in 1919.

"Everyone says the shooting stopped at 11 o'clock on the 11th [hour] of the 11th [month] and that's not true," said Ms Styles.

"Whether it was someone cleaning their gun and it was an accident, or it was a German not believing the armistice [was] in place, we don't know."

But the club and fans did not forget their former players. One fundraising event held not long after Billy Smith had been wounded raised £40 for him, the equivalent of about £4,000 today.

In a letter to the club, Smith said he could not kick a football with his new leg so he would have to be an umpire instead or settle for a place among the spectators.

Arthur Evans, one of the team's professionals who did not travel on the tour, was among those who did not return.

He rose to the rank of sergeant while serving with the 24th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, which was known as the 2nd Sportsman's Battalion.

Evans was killed during the Battle of the Somme on 31 July 1916 and is among the more than 72,000 officers and men from Great Britain and South Africa who are listed on the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval, in northern France.

"As a whole, the ones that went to Brazil were a very lucky group," said Ms Styles.

"When you compare other teams, so many of them died and for a team of this size to have gone [to war] and all come back is surprising."

How 41 Clapton Orient players joined the 17th (Football) Battalion and the rise of the Munitionettes' League.

- Attribution

- Published25 July 2014

- Attribution

- Published22 July 2014

- Attribution

- Published21 July 2014

- Attribution

- Published18 July 2014