Transracial adoption: 'I bit my hand hoping my skin colour would change'

- Published

Sally Stormont wants her one-year-old daughter Bebe to feel like she belongs

"I've been bullied in school to the point I remember biting my hand, hoping my skin colour would come off. Having white parents doesn't protect you from racism. Parents need to understand that."

Six years ago, the law was amended to make it easier for children to be placed with parents of a different ethnicity. It was in order to deal with a care crisis, especially when placing children from black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds in permanent homes.

However, some transracial adopters and adoptees say doing so, without proper support and caution, can lead to an identity crisis.

'My parents thought they were doing me a favour by adopting me'

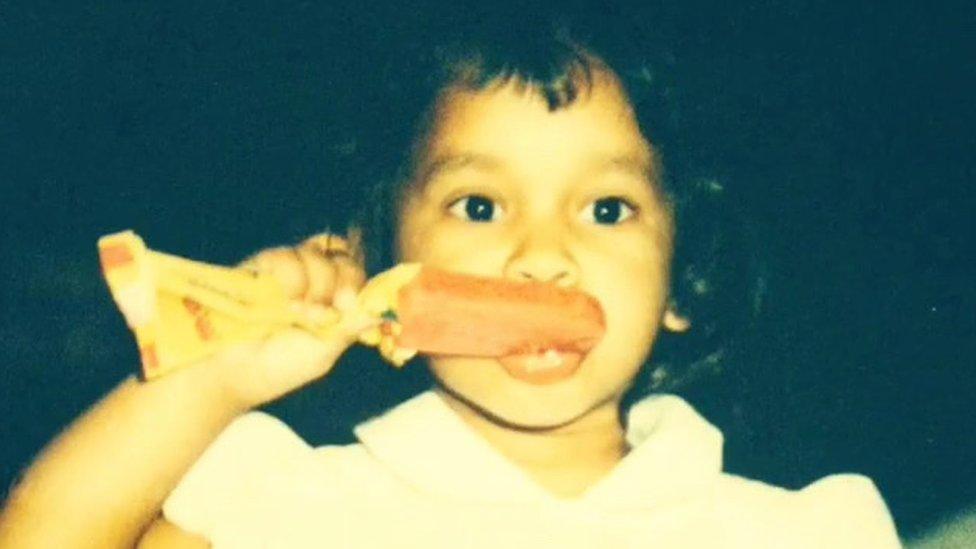

Sally Stormont says she had identity issues growing up

Sally Stormont is of Sri Lankan descent and was adopted by two white English parents. She spent most of her school years in Devon, where in most instances, aside from once or twice there being a mixed-race pupil, she was the only person of colour in her school.

"My family and friends would say they don't see colour, that they see me as 'one of us', as if my colour is something to be embarrassed about," she says.

"I guess, at some point I felt like it was."

Ms Stormont says she grew up having issues with her identity. Not being taught about her Asian heritage at home meant she didn't fit in among South Asian people when she was older - leading to feelings of isolation.

"I've been told things like, 'you have white parents, so you're not really Asian' or 'why don't you know how to cook curry?'," she says.

"It's embarrassing when Asian people want to know where I'm from and I have to tell them I really don't know. I've never felt good enough.

"All I know is a white family and white lifestyle, but I'm not white. I'm like a hologram. I feel empty, like I'm a fraud on both Asian and English sides."

"I'm like a hologram. I feel empty," says mum Sally Stormont, who was adopted by two white parents

Ms Stormont wants it to become a requirement for adoptive parents to learn the heritage of their adopted children. She believes there is not enough support for those adopted by parents of another ethnicity.

"My parents thought they were doing me a favour by adopting me," she says. "Instead, I grew up without seeing people like me. I've always felt very much an anomaly and still do.

Ms Stormont says she hopes to visit Sri Lanka one day, but says for now she's focused on raising her one-year-old daughter, Bebe.

"I've already had comments about how she's the 'perfect shade', because her father is white," she says. "I don't want her growing up to feel the way I did."

'My parents knew to help me understand my ethnicity'

Luke Bacon wants his own children to be comfortable with who they are

Luke Bacon, who is half English and half Ghanaian, grew up in several countries - Wales, England, the Netherlands and Botswana. He says he appreciates his white Welsh parents' decision to expose him to different cultures.

"They understood part of their parental role was to help me understand my heritage," he says.

"My parents were good and deliberate in giving me opportunities to talk about being adopted and being of mixed heritage."

The only time Mr Bacon says he was made to feel different and had his identity "pigeonholed in a binary way", was while he was living in Kent as a teenager.

"There were the second glances at me, or I would be referred to as the 'black' friend," he says.

"I remember during a church service on the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, an older lady came up to me to apologise for slavery - like I represented an entire race of people.

"I realise how a lack of racial diversity around a child could make their upbringing difficult. I'm so genuinely grateful for the one that I had."

Mr Bacon says it has assisted him and his partner with bringing up their adopted mixed-race daughter, who has struggled with accepting her skin colour and hair texture in the past.

"I want to teach her to live life true to herself and to be comfortable in who she is," he says.

Government figures show 3,570 children in care were adopted last year

Latest figures from the Department for Education, external show out of 80,080 children in care in England, only 3,440 were adopted in the year up to March 2020.

More than 25% of children in care are of black, mixed or Asian heritage, according to the NSPCC.

Adoption authorities admit black children have to wait longer than white children to be placed in permanent homes, some up to a year longer.

According to the charity Home for Good, external, BAME adults are more than twice as likely to consider adoption than white adults.

It also found 52% of UK adults open to or who have already adopted or fostered, would prefer to adopt a child of the same ethnicity as themselves.

'My daughter has told me she wishes she was white'

"I don't think everyone really understands the impact on the child of living with parents with a different ethnicity"

Martha*, from Plymouth, has two young adopted mixed-race children. Martha admits she was naïve when she began the adoption process and says parents who ignore the "colour" side of their children are being unfair to them.

"Race isn't something they can escape from," she says.

"I remember going to the post office and a woman asked whether my daughter was the result of a holiday romance with a 'darkie'. I was mortified.

"At school, a bully once asked my eldest Danni* why she doesn't just 'wash the colour off her face'. Danni has told me she wishes she was white."

Martha thinks the government needs to do more to better prepare interracial adopters.

"There needs to be more emphasis on white privilege during the three days' mandatory training for adopters," she says.

"I don't think everyone really understands the impact on the child of living with parents with a different ethnicity nor how much these children lose."

One way around this for Martha is to make sure her friend circle is made up of people from different ethnicities and backgrounds, with whom her children may better relate on racial issues.

"I've got all these friends around me to help me raise them," she says.

'We want to help prospective adopters open up their thinking'

"What's important is finding families who can teach our children how to love and be loved"

Clinical psychologist, Dr Nneamaka Ekebuisi, says the government should be more proactive in providing mandatory support for both parents and children.

"There has been a real underplay of race and its impact on a child," she says.

"Adopted children already have the trauma of being removed from their birth family, which might involve issues with attachment; but then being placed with a family that doesn't look like them means they're going to have questions.

"It can bring about feelings of shame and rejection. It will impact on their sense of belonging and their identity formation."

Dr Ekebuisi believes the Adoption Support Fund, external - a government grant that helps families get therapy - could be extended to help interracial families.

"Black people have to talk about race and racism to their children from day dot," she says.

"White people have the privilege to not need to do that. But as a mixed-race adopter, you have to realise that you are no longer afforded that privilege."

'Love and be loved'

Kath Drescher, from the South West's Regional Adoption Agency, says the government is campaigning to dispel myths around adoption and attract more BAME, LGBT and single-parent adopters.

"It takes longer to place a child of a black, Asian or other ethnic minority background with a family and we're trying to figure out why that is," she says.

"We know there are lots of potential BAME adopters out there.

"We've had white adopters in remote villages concerned about how it will be for a BAME child. We need to look into how we currently support our families, as a way to then recruit more.

"We want to help prospective adopters open up their thinking about the child they want to adopt.

"What's important is finding families who can teach our children how to love and be loved."

*Names have been changed to protect identities

- Published28 April 2020

- Published14 October 2019

- Published2 July 2019