What do we know about unexploded WW2 bombs?

- Published

A bomb was detonated in a controlled explosion in Exeter

Hundreds of thousands of bombs were dropped on Britain during World War Two, some of which never exploded, so perhaps it should not be a surprise that they are still being found more than 75 years after the end of the war. But how much do we know about them?

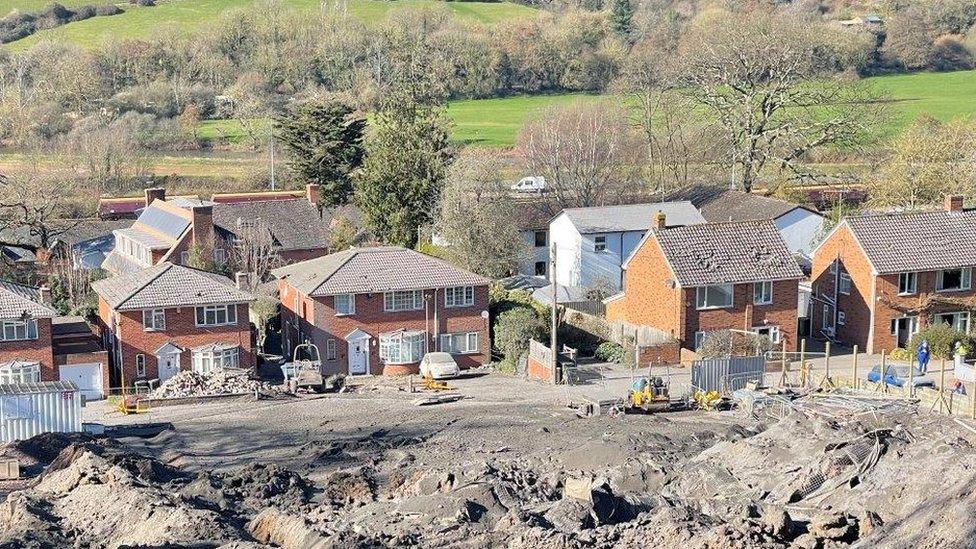

The discovery of an unexploded World War Two bomb in Exeter resulted in a military response, thousands of residents being evacuated from their homes and extensive damage to nearby properties.

After being discovered on an allotment due for development, the 2,200lb (1,000kg) German bomb was blown up on Saturday in a controlled explosion, leaving a crater the size of three double-decker buses.

Residents have all been allowed back into their homes but many of the properties are "uninhabitable" according to Exeter City Council. About 300 students are still waiting to be allowed back into their accommodation.

The BBC has spoken to a series of experts about the wider questions surrounding unexploded ordnance.

How did the bomb get there?

Bombs created destruction around the city's cathedral in 1942

Exeter was the first victim of the Baedecker Raids on English cultural centres during World War Two, made in response to the British bombing of Lübeck.

The raids were named after the Baedeker guidebook used by the German military to select historic targets in England.

The Blitz of Exeter in April and May 1942 "was the single most destructive event in the city's history since at least the attack by the Vikings in 1003" said Dr Todd Gray.

The historian from the University of Exeter said the recently discovered bomb most likely fell during one of these attacks, when the city was targeted for morale rather than for strategic purposes.

Nearly 300 people died, more than 1,700 buildings were destroyed, 7,000 high explosives and incendiary bombs were dropped and 40 high explosive bombs did not detonate.

The 2,200lb (1,000kg) German bomb was discovered on an allotment due for development and blown up on Saturday

The sound of the bomb being exploded on Saturday was "ferocious", but Dr Gray said he felt "quite thankful" to have heard the noise as a reminder of what it would have been like at the time.

"That bomb going off reminds us what that generation in 1940s went through," said Dr Gray.

"It's sobering, but now and then something like this is good for us to think about."

The bomb was discovered near Exeter St David's railway station in an area not covered by a "bomb census".

"There's bound to be I would have thought one or two more somewhere," he added.

Could there be more nearby?

Three hundred people were killed in Exeter during the first of the Baedecker Raids

Emily Charles, a World War Two curator at the Imperial War Museum said the exact number of bombs across the country was not known and it was "really hard" to work out where unexploded bombs could be.

The allies kept a detailed record of bomb damage inflicted on British cities during the war called the bomb census, said Ms Charles.

They created maps to show the most damaged areas, which can give historians a "better picture" of where unexploded ordnance could be, she added.

The most common type of bomb used in the Blitz was about 500lb (226.8kg), meaning the 2,200lb (1,000kg) bomb detonated in Exeter was "particularly large" said Ms Charles.

However, she stressed it was "not uncommonly large" and bombs of this size had been found in recent years.

Could they explode?

The crater was big enough to accommodate three double decker buses, a structural engineer said

A guide on managing the risk of unexploded devices was released by the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) in 2019.

The CIRIA guide said ordnance could be reactivated by either direct impact, vibration or heating.

The lack of fatalities in instances when construction teams discover unexploded devices "is particularly because of the Germans commonly using electrical fuses in WW2 that stopped functioning when the battery expired", said the guide.

"What makes unexploded bombs dangerous is their unpredictability," said Ms Charles.

She told the BBC there were "not huge scientific studies" on how explosives degraded or whether they got more deadly over time.

"So I think the best course of action is to treat them as if they are deadly."

That the bomb was detonated in a controlled explosion and houses suffered damage, proves they can still be dangerous, she said.

There are multiple reasons that bombs do not detonate upon landing, explained Ms Charles, such as faulty fuses, defects or the way they land.

She said people should call the police if they spot any suspected explosive devices.

How much is there across the country?

The explosion from the bomb being detonated was heard up to five miles away

The Ministry of Defence says since 2010 it has been involved with making safe 450 German WW2 bombs - about 60 a year, the BBC Reality Check team revealed in 2018.

However, these figures do not factor in the involvement of private companies that can also dispose of unexploded devices.

This can make it difficult to establish exact figures for how many are dealt with each year across the country.

A specialist from one such private company, Zetica UXO, told the BBC that since World War Two "45,000 unexploded bombs have been found and more are being found all the time".

Official records, which can often be understated, predicted around "200,000 plus bombs were detonated" during the war said Mike Sainsbury.

He said it was estimated that "another 10% or so" did not explode.

The CIRIA guide reveals an estimated 15,000 items of unexploded ordnance were removed from construction sites between 2006 and 2008 by three clearance firms.

Clearance efforts after World War Two were extensive, but some unexploded devices were "either deemed not to present a risk… or too inaccessible for practical removal", said the guide.

How to detonate an unexploded bomb?

The controlled explosion left a crater behind

Bomb disposal experts say they had no choice but to detonate the bomb because the fuse was so corroded they could not tell what type it was, or if it had been booby trapped.

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said explosive ordnance teams from the Royal Navy and Army worked with local authorities to safely dispose of the bomb.

Military teams worked for 24 hours to build protective structures and trenches to minimise the impacts of the blast and used more than "400 tonnes of sand" to mitigate the explosion.

Follow BBC News South West on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to spotlight@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published3 March 2021

- Published2 March 2021

- Published1 March 2021

- Published28 February 2021

- Published27 February 2021

- Published26 February 2021