'Problem teenagers' taught to be horse whisperers

- Published

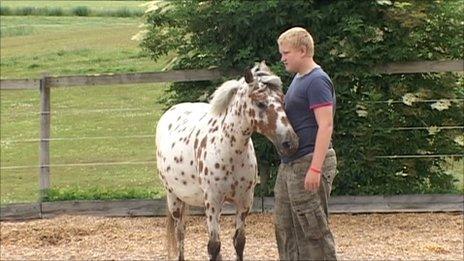

Ross Pettitt has ADHD and he says working with horses has helped him calm down and concentrate a lot more

Can learning to be a horse whisperer help children with behavioural problems?

One woman from Dorset is offering therapy to children and teenagers by teaching them to communicate with horses using the principles of natural horsemanship - talking to horses in their own language.

The technique is most famously associated with the Hollywood blockbuster film The Horse Whisperer starring Robert Redford.

Tricia Day says teaching the children how to talk to the horses helps them learn about themselves, grow in self-confidence and become less aggressive.

At Tricia's farm in a valley near Shaftesbury, Ross Pettitt is taking Blossom the pony across an obstacle course inside a round pen.

Blossom is freely following the 17-year-old. She is not wearing a head collar and Ross does not have to say many words to her to tell her where he wants her to go but instead communicates through his body movements.

Ross, who lives with a foster family in Milborne St Andrew near Blandford, was referred to Tricia through his social worker.

He has been diagnosed with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and has recently also been told by doctors he could have Asperger syndrome, a form of autism characterised by difficulties in social interaction.

Tricia says when Ross arrived for his first session he did not even want to meet the horses.

When we meet he has been coming for regular sessions for two months and the difference is clear to see.

Princess Anne came to see Tricia's work with prisoners at Guys Marsh

"We have two dogs at home which I wound up before, but since I've done this it's taught me to leave them alone a lot more," he says.

"When I first came I was quite worried. I'd never interacted with horses before and they're really big animals.

"Getting to know how the horses work has helped. When Blossom settled down, it calmed me down and I was able to do what I wanted to do.

"I've really enjoyed it. It's helped me concentrate a lot more in life."

Tricia, 53, has set up centres across the country and calls her work horse therapy or equine facilitated therapy, describing it as "experiential learning".

"It helps because people experience a real situation, can discuss what has happened and make changes to their behaviour," she says.

Of the teenagers she helps, many have behavioural problems, they may have been excluded from school or have picked up criminal convictions.

"We're able to help people with their own self-awareness and their own self-development by just putting them in a space with a horse. It's just about interacting with the horses."

Impossible to bluff

They are told that to gain a horse's trust they have to be still and quiet, or the animal will become nervous and if it is frightened, it will flee.

Tricia says a horse reacts instantly to a person's energy and body language because that is how the animals communicate with each other.

They sense the underlying state of mind of a person, so it is impossible to bluff a horse, she says.

It is not the first time Tricia has used her work to help people seen as having problems - she has previously taken them into Guys Marsh Prison in Dorset.

She says: "I took my horses into prison for the first time in 2005. I was teaching there and we did a communication course with the prisoners.

"That was amazing for them - for things like anger management and those sort of things it was super."

Spott used to to be frightened of many things but after much work he is now a much calmer horse

She took five of her horses with her and stabled them at the prison for a week.

Princess Anne - well known for her love of the equestrian world - came to visit her there after hearing about the impact her work was having on the prisoners.

"It helps to make people more self-aware," Tricia says. "The guys in the prison were saying that some of the people had to 'drop the bravado' in order to get close to the horses.

"You can be really brave on the outside but you need to be a certain type of person on the inside to get close to the horses.

"They [the horses] don't see people's baggage, they don't have labels for people so they just work with people as they are"

Fear of riding

Tricia says she tries to adopt the same attitude and treat the people she works with in the same way the horses do.

They may be prisoners, teenagers in trouble with the law, children playing truant or youngsters with behavioural problems but she says she does not look at their past and only tries to help them for the future.

"It probably all started because I had a fear of riding years ago," she says.

She went halfway around the world to Australia and knocked on the door of a well known horseman called Steve Halfpenny. He helped her a lot, she says.

"It was by talking through horse handling techniques and thinking a bit about natural horsemanship that I was realising how that sort of work was making a difference to me on the inside."