Bournemouth researchers tackle 'face blindness' cause

- Published

The awkwardness of asking someone out as a teenager is bad enough - but for Paul Schofield not recognising the girl he liked made things even worse.

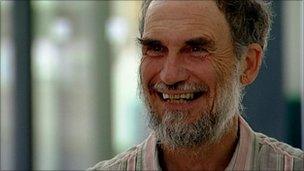

For Mr Schofield, now aged 63, the moment he experienced the confusion was the first indication he had prosopagnosia or "face blindness".

It is a condition, the Isle of Wight resident says, that still makes him feel embarrassed and socially awkward.

Now, he is hoping that taking part in research carried out at Bournemouth University he will finally understand what causes it.

The memory of realising he had problem while he was at secondary school, is still strong in Mr Schofield's mind.

"I met a girl and quite liked her, and I called round to her house to ask her out," he said.

"When the person answered the door I said, 'Is Loretta in?'. She was Loretta, I didn't recognise her.

"[Prosopagnosia] prevents you from being more forward, people really don't like not to be recognised."

Paul Schofield discovered he had the disorder when, as a teenager, he failed to recognise a girl he liked

Researchers are hoping a test to record people's eye movements will produce results to help sufferers who say they live in a state of low-level confusion and cannot recognise members of their own family.

Sometimes those who have it even have difficulty placing their own faces.

"It's absolutely specific to faces, they know what a face is, they know the basic configuration of a face but they just fail to identify individuals no matter how close those people are to them," Dr Sarah Bate, Bournemouth University said.

Researchers at the university estimate that one in 50 people in the UK suffer from some form of the condition.

The study involves sufferers like Mr Schofield looking at a number of faces for five seconds, with a recording made of his eye movements as he processed what he saw.

When it was carried out on people without the condition, the test showed they looked at the face with a regular triangular pattern of movements, which moved about from the eyes, nose and mouth.

It is believed people with the disorder do not form the triangle from the eyes to the nose and mouth.

'Possibly hereditary'

"Paul focused on less individual features, doing almost the reverse," Dr Bate said.

After the test Mr Schofield said: "I discovered that I was actually looking at the person's mouth more than the eyes, whereas in my mind I was looking at the eyes quite a lot.

"We also discovered that I was looking at a wider field of view, people's ears and their foreheads."

There is no cure for the condition which could be hereditary. Sufferers say they cope by remembering non-facial information like someone's voice or hair style.

Prosopagnosia features on BBC Inside Out South on Monday, on BBC One at 19:30 and on BBC iPlayer.