Bevin Boys meet for last reunion in Bournemouth

- Published

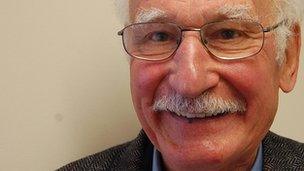

Warwick Taylor was conscripted into service as a Bevin Boy at the age of 18

Since 2008 the Bevin Boys Association has lost more than 2,100 members.

Nationally it now has only 600 surviving members and its numbers continue to decrease dramatically.

That means Thursday's annual reunion for its 30 southern counties members could be the last, according to the vice-president, Warwick Taylor.

"We are all 86 years of age and I've lost 52 members since January," he said. "It is rather sad but time goes on, this is what happens."

At one time there were more 48,000 Bevin Boys.

In December 1943, when Britain was at war with Nazi Germany, its industry was at full stretch and there were only weeks of coal supply left.

In a move to bolster production Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour and National Service, introduced a ballot for conscripted men.

Men, who had signed up expecting to fight in the war, were instead sent underground and among them was the 18-year-old Warwick Taylor.

"It was pretty tough," he said remembering that moment almost 70 years on. "I didn't want to go there at all, I wanted to go into the RAF.

"But my number was drawn out of the hat and that's it."

The men were named after the wartime labour minister Ernest Bevin

'Deadliest enemy'

Had he refused he would have faced a three-month spell in a prison cell - which might have been better than the situation he faced in collieries of South Wales where he was sent.

"The conditions were pretty rough, believe you me, and of course the main thing was, it was dangerous.

"It was an entirely dangerous job because of roof falls and fire damp. Methane gas was the deadliest enemy. You got many explosions and it used to kill dozens of people at a time."

But despite putting their lives on the line to keep the country's industry running, the men got very little recognition for their work.

It was not until 2007 that applications were invited for the special commemorative badges to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the demobilisation of the last Bevin Boys.

During the war they were widely derided and suspected of being conscientious objectors.

Mr Taylor said: "You used to get stopped by the police quite regularly because you weren't in uniform, and we got a lot of abuse from local residents."

The Bevin Boys were sent to work in the country's 1886 coal mines

But he was in venerable company: Eric Morecambe and Jimmy Savile were both Bevin Boys, for instance.

They toiled in the country's 1886 coal mines, helping to power the munitions factories and heavy industry needed to keep the war effort on track.

"It was important," said Mr Taylor. "We probably didn't realise it at the time but I think we do now. Hindsight is a wonderful thing and I think we did make that contribution that was vital to the war effort."

Now at 86 the Dorchester resident will travel to the Miramar Hotel in Bournemouth on Thursday for possibly the last time.

"It will probably be the final one as we find our numbers are getting less and less each year," he said.

"There will be a lot of reminiscing, a lot of camaraderie and a lot of laughter."