Tyneham: Dorset's lost D-Day village

- Published

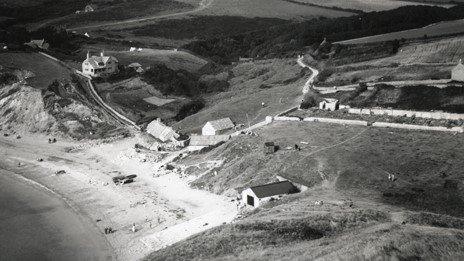

The village of Tyneham was taken over by the military in 1943

Over one month in 1943 a group of residents was ordered to leave their Dorset village after the government took it over for military training. Seventy years on people are being warned not to take a rose-tinted view of the village which was left "frozen in time".

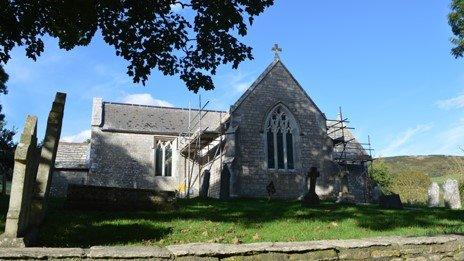

'Thank you for treating the village kindly', read a note pinned to Tyneham's church door as the final inhabitants hurriedly left in 1943.

The estate and village, nestled near the Dorset coast, had been commandeered as a tank firing range ahead of D-Day with its 225 inhabitants told to leave their homes.

They never returned.

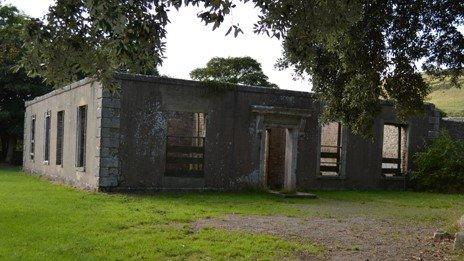

After seven decades, the roofless shells of a post office, farmhouses, a rectory and cottages offer passing curious walkers and visitors a glimpse of the life of a long-departed community.

'No small sacrifice'

The 3,003 acre site on the Tyneham estate near Wareham was owned by the Bond family for more than 300 years.

In the autumn of 1943, villagers were given just over a month's notice to leave their homes, under the blanket of intense secrecy which cloaked all plans for D-Day.

An official letter stated: "The Government appreciate that this is no small sacrifice which you are asked to make, but they are sure that you will give this further help towards winning the war with a good heart."

The villagers were initially promised they would be able to return to their homes when the war was over. But the demands of the Cold War meant the post-war Atlee government kept the land for military use.

Major-General Mark Bond, 90, is among a handful of surviving former residents of the estate.

A son of the landowning family, he had been a prisoner of war and only learnt of the takeover when he was picked up by his father from Wareham station in 1945.

"My father greeted me and I remember being in the car when he told me 'We're living in Corfe Castle'," he said.

Mark Bond was a prisoner of war when the estate was emptied

Maj-Gen Bond describes his father's feelings at the loss of their ancestral home as "resigned patriotism".

"He understood with the war coming to its climax it was absolutely necessary to give tanks the proper training area," he said.

Looking at what remains of the village today, Cdr Bond admits to "mixed" feelings.

"It has its old magic and a rather sorrowful background," he said.

"I'm sad that what I knew of the people and the village no longer exists and the houses are in ruins."

In subsequent decades there were calls by some residents for a return to the village.

Resident John Gould wrote to prime minister Harold Wilson in 1974, pleading for the village to be returned to the people.

"Tyneham to me is the most beautiful place in the world and I want to give the rest of my life and energy to its restoration ... Most of all, I want to go home," he wrote.

Then and now - Post Office Row was the centre of the village

Small reminders of domestic life can still be seen among the ruins

Worbarrow Bay's fishing industry was already in decline

The rectory was one of the largest buildings in the village

Tyneham church was re-opened in 1979 and is used for carol concerts and remembrance services

Lynda Price has spent 20 years researching the village's history and creating displays for visitors. She warned against a rose-tinted view of Tyneham.

"While it was a traumatic experience, especially for the older residents, many people don't appreciate it was basically a feudal set-up with people working for the Bond family.

"The coming of the motor car was a death knell - why only work in the fields when you could have a car and work elsewhere?," she said.

The school had already closed in 1932 because of a lack of pupils.

Modern farm machinery meant fewer jobs on the land while the estate's fishing community at Worbarrow Bay was hit by new trawlers operating out of Weymouth.

While the Bonds received £30,000 in compensation for the loss of their land, most tenants lived in tied houses and had no official property of their own. They were reportedly only compensated for the vegetables in their gardens.

"Nevertheless, they had electricity in their new homes and running water, rather than having to queue at the village pump," she said.

A return to the village was also made less likely as local builders helped themselves to materials.

"There was a lot of pilfering after the war. It was under the radar but everyone knew it was happening," said Ms Price.

The MoD eventually made the ruins accessible at weekends, external when training is not taking place.

'Refugees of war'

Stanford in Norfolk and the Wiltshire village of Imber suffered a similar fate during World War II.

What would have happened to Tyneham if the residents had returned is a matter for debate - its location on the Jurassic coast means it could well have become another Dorset tourism hotspot with hotels, cafes or caravan parks.

As it is, Worbarrow Bay is one of the most tranquil and isolated spots on the coast and while hundreds of people visit the site each weekend, bylaws prevent the sale of any goods and its development as a conventional tourist attraction.

"It's just a joy - from the story you get a sense of belonging and can foster the nostalgia and the feeling of it being frozen in time," said Ms Price.

A new musical tells the story of the Dorset village taken over by the military during World War II

Aiming to recognise the sacrifice of the residents, a group of singers and musicians are staging a musical based on the Tyneham story.

Producer Geoff Tizzard King described them as "refugees of war".

"I was always fascinating by Tyneham. Every time I visit I've come away captivated and slightly haunted, I guess.

"It's a story of human determination and stoicism. It was an awfully sad thing to happen to a community which had been there for hundreds of years, but they really took it on the chin," he said.

Exploring deserted Tyneham at dusk when all the visitors have left and with the sun dipping over Worbarrow Bay, is when the musical's anthem seems most poignant - 'Can you hear the whispers in the walls?'.

- Published18 November 2010