Have Olympic towns Weymouth and Portland been forgotten?

- Published

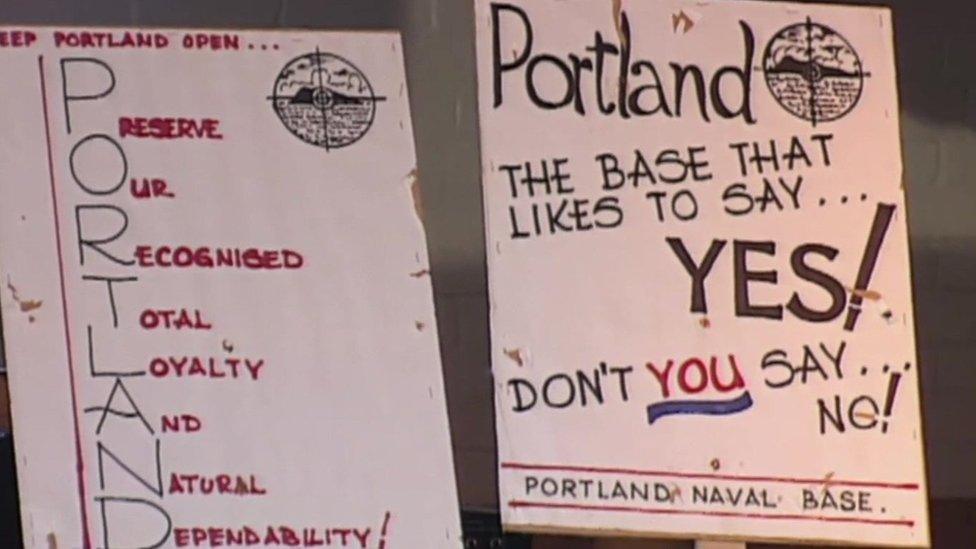

During its heyday, the area around Portland Port was bustling with activity

Their roles as hosts of the 2012 Olympics should have put Weymouth and Portland on the map, but little more than a decade later they have been branded "forgotten towns".

A 2022 report by South Dorset Research Group concluded that the seaside resort and neighbouring peninsula were stuck in a vicious circle of "poor job prospects and low earnings".

So how did things end up like this?

Despite its location on the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site, the area never recovered from the economic collapse sparked by the departure of the Royal Navy in the 1990s.

"I could leave a job on a Monday and have a new job on a Tuesday," said Russ Haylor, reminiscing about Portland's heyday.

Russ Haylor said in the mid-1960s Castletown was once lined with pubs

"I managed to get in the dockyard in 1978. Within days of being in there I knew it was like winning the lottery."

"They were jobs for life in those days," added fellow resident Stephen Downton.

"We had prospects - I left school with one O-level and I failed my 11-plus but I had three or four apprenticeships offered to me and I ended up a principle hydraulic designer at Leonardo Helicopters."

In 1992, before the navy left, more than 41% of jobs in Weymouth and Portland were linked to the defence industry but, three decades on, young people there are facing a less certain future.

Apprentice engineer Reef Butler says 90% of his friends have left the area

Reef Butler, an apprentice engineer, said: "Most people we know have already gone - 90% of our friends have left and, the careers they are going for, they probably won't come back.

"Weymouth is quite good for engineering. There are quite a few companies but most of them are quite small and can't take on apprentices."

And it's not just the lack of job opportunities that have been a cause for concern.

The three secondary schools in the area have either come out of special measures or are undergoing a turnaround programme and, proportionally, fewer pupils go on to university than the national average.

Weymouth and Portland hosted the London 2012 Olympic sailing events

Six years ago the area had three full-time and three part-time youth clubs, but cuts by the former county council mean just one full-time and two part-time clubs remain.

Youth worker Tom Lane, of the charity-run Steps Club in Chickerell, described it as a "decimation of youth provision".

He said: "We are failing our young people and not providing them with the opportunities they need to survive and to thrive and move into their adult lives with a strong chance of success.

"We've taken a lot of the support things away and left our young people to sink or swim and a lot of them are sinking."

Rachel Braund volunteers at a toddler group and a food bank

Despite its problems, people in Weymouth and Portland say the community spirit is strong and volunteers have been stepping up to help people in need.

Rachel Braund, who volunteers for Islanders Mother and Toddler Group as well as her local food bank, said: "It's the community coming together but we are just so underfunded and that's sad. It's such a beautiful place but we are being forgotten."

Sue Beacock, who runs the toddler group on a voluntary basis, said: "The Portland community is strong but it's poor - there's a lot of drugs, there's a lot of alcohol, there's children doing without.

"There's all sorts of things that could be done but there isn't the money to do it."

Linda Fitzsimmons says a lot of older people would not cope without help from charities

Another local charity, Island Community Action (ICA), supports people to live happier, healthier lives as well as tackling serious problems such as loneliness and malnutrition.

Linda Fitzsimmons, who is both a service user and a volunteer, said: "I do feel that if it wasn't for Island Community Action, myself and an awful lot of other older people would not be able to cope."

ICA chief executive Kim Wilcocks said: "We've got this ageing population but decreasing numbers of younger people as they move off the island to look for opportunities.

"Its community is phenomenal but it has massive challenges and it's been going on now since the navy left."

Island Community Action supports people to live happier, healthier lives

Dorset Council's councillor for economic growth, Tony Ferrari, described the 2022 Forgotten Towns report as "unhelpful" for the tourist resort.

He said: "I think this is a history lesson, not a description of Weymouth as we see it today.

"There's a whole list of things that have been done by the council, and the private sector has bought into that.

"Weymouth has turned the corner and is going in the right direction."

But Prof Philip Marfleet, who co-authored the report, disagrees.

The closure of the Royal Navy's base at Portland sparked protests

He said: "In 2018, the government's own figures showed us that social mobility in south Dorset was the lowest in the whole of England.

"These give you an idea of how serious and rapid the decline, economically and socially, has been in what is the largest urban area in Dorset Council's local authority.

"Weymouth and Portland are fine places to live and the communities are very resilient but the overall record of decline continues."

Dorset Council said evidence for the growing success of Weymouth and Portland was demonstrated by housing and employment figures.

It said since 2019, 524 new homes had been built and there were a further 2,526 homes with planning consent, while unemployment in November was 3.3% compared with the national figure of 3.7%.

A spokesperson for the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) said: "Dorset has received £6m through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund to invest in local businesses, people and skills."

The department is due to announce recipients of the second round of Levelling Up funding by the end of January.

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.