Mum with children in care describes agreeing to contraception pact

- Published

The scheme has proved controversial with some women's rights groups

Mothers who have had two or more of their children taken into care are being offered life-changing support - but only if they agree to using contraception for 18 months. Critics have said help for vulnerable women should not be contingent on anything. But one mother who spoke to the BBC said she was happy to accept the condition if it meant getting her life back on track.

"You just feel lost... You just feel useless, because you're a mum, then you're nothing," said Amy, who has faced seeing two of her children taken into care.

Amy, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is one of more than 1,000 women across the UK to have been supported by the Pause Project, which is now offering its services in Dorset.

She said the charity, which requires women not to get pregnant while receiving their help, was essential to help her focus on overcoming her struggles and becoming a better mother.

"It was my fault. That was my one job, and I didn't do it, and that made me feel guilty, which also sort of spun me down a bad path," she said.

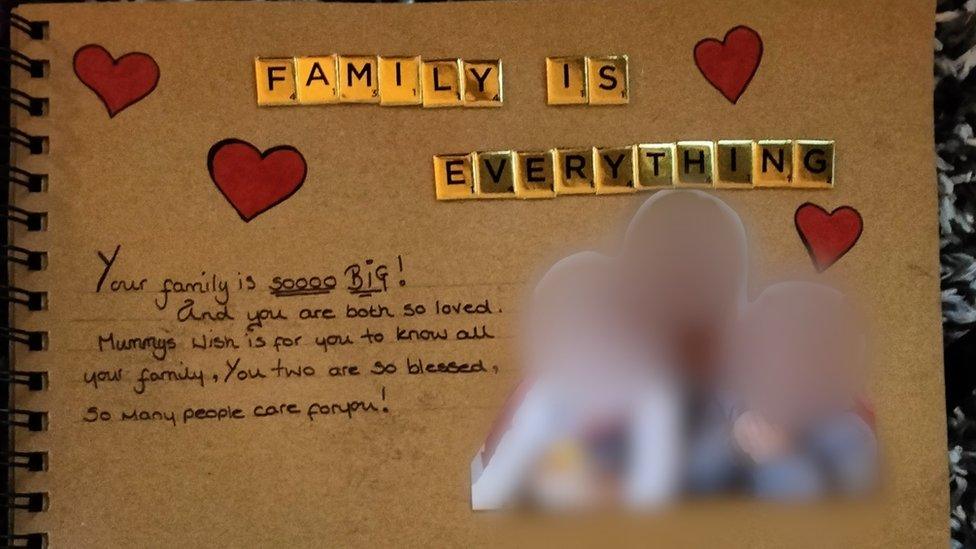

Amy keeps pictures of her children in a cherished photo album

That path included drugs, homelessness and mental health problems.

Amy was a teenager when she escaped her own chaotic, dysfunctional family home, into what became an equally chaotic life with her childhood sweetheart.

They tried and failed to keep a permanent roof over their heads.

After getting pregnant, Amy ended up in housing for single mothers and their babies, while her boyfriend remained homeless and continued taking drugs.

"We had quite a volatile relationship," she said.

Amy explained how social workers wanted her to cut ties with her partner, and how instead she believed his promises to give up drugs.

"You want that family unit, so I'd lie to them and say 'oh I'm not seeing him'," she said.

A court ruled Amy's son should be taken into care

But the lies Amy told were exposed by CCTV pictures showing him visiting her and their son at home.

A court ruled her son should be taken into care immediately, with his mother being allowed to see him just six times a year and under supervision.

"I remember coming home from court and I hated it," she said.

"Sort of not really knowing what to do, because I was used to changing nappies, making bottles and I literally had none of that to do.

"I just thought, why didn't I just listen and do what they said."

With no baby, Amy lost her home and ended up on the streets again. She eventually fell in love with someone new and became pregnant for a second time.

"I immediately stopped taking drugs. I even went for voluntary drug tests, to sort of over prove myself," she said.

"We were housed. We were going to our child protection meetings and they said that things were going really well."

Amy was helped by the Pause Project after her baby daughter was taken into care

But Amy's partner - her unborn baby daughter's father - died suddenly and unexpectedly.

She started suffering with mental health issues including depression and anxiety.

"I was just so scared of losing my daughter, because she genuinely was all I had left. I'd lost my son. My partner was now gone. I literally just had my daughter," Amy said.

Petrified of losing her, Amy tried to hide her depression and grief from social workers. But she could not cope and had an acute psychotic episode and a mental breakdown.

Amy's baby daughter was taken into care.

It was after that happened that Amy was helped by the Pause Project.

The scheme asks women to commit to use contraception for the duration of its 18-month-long intensive support.

Asking women to agree not to get pregnant, in exchange for help, has proved controversial with some human and women's rights organisations.

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service has said it opposed help to vulnerable women being contingent on them receiving a specific form of contraception.

In a statement on its website, it said: "The Pause programme raises ethical issues that need to be engaged with, and we would do well to ourselves pause and reflect before it is rolled out any further."

Concerns have also been raised previously in Scotland where some critics said the scheme raised "big ethical questions" about conditional welfare and reproductive rights.

The charity asks women to take up contraceptive for more than one year

However, Amy said the Pause Project had helped her to focus on what was important.

"I know a lot of women don't understand why you have to do that. But you need that time to take a step back from having children," Amy said.

"You need to rebuild who you are, because once you've lost one child, it's a repeat removal situation, and you can't keep putting yourself through that or your kids through that."

She is now working part-time and and studying for a career in social care.

"Pause helped me get the right professional help," she said. "I started looking after myself, so my life's vastly improved."

She is now able to see her children regularly.

"I just didn't want them to grow up and think well, you just completely gave up, because that's not the case," she said.

"It's not the case for women that do spiral out of control.

"They haven't given up on their kids. They've given up on themselves."

In Dorset, the new Pause Project workers have been knocking on the doors of dozens of local mothers who have had their children removed, to offer them the type of sustained help Amy said she desperately needed.

Rachel Young leads the Pause Project in Dorset

"When children have been removed, there isn't anything to pick that woman up and support her," said Rachel Young, the practice lead at Pause Dorset.

She explained that many of these women had grown up with trauma and had often been "repeatedly let down by services".

Pause practitioners nurture close relationships with women, in the hope of breaking trans-generational cycles. They help them maintain contact with their children and get access to housing, healthcare, counselling and substance addiction services.

The project in Dorset is run by Bournemouth Churches Housing Association and funded by Dorset Council.

"If nothing changes for that woman, nothing changes in terms of the outcome. So their next pregnancy is likely to go the same way," Ms Young explained.

She said the name of the project reflected the pause in pregnancy women were asked to take.

Ms Young said women would decline the service if they did not want to commit to long-term reversible contraceptives.

"But for the programme to make the impact that we want it to make on their life, they need to be able to focus on them and their needs only, rather than the additional concerns around pregnancy," she added.

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.