Fake duke Alexander Wood and other impostor aristocrats

- Published

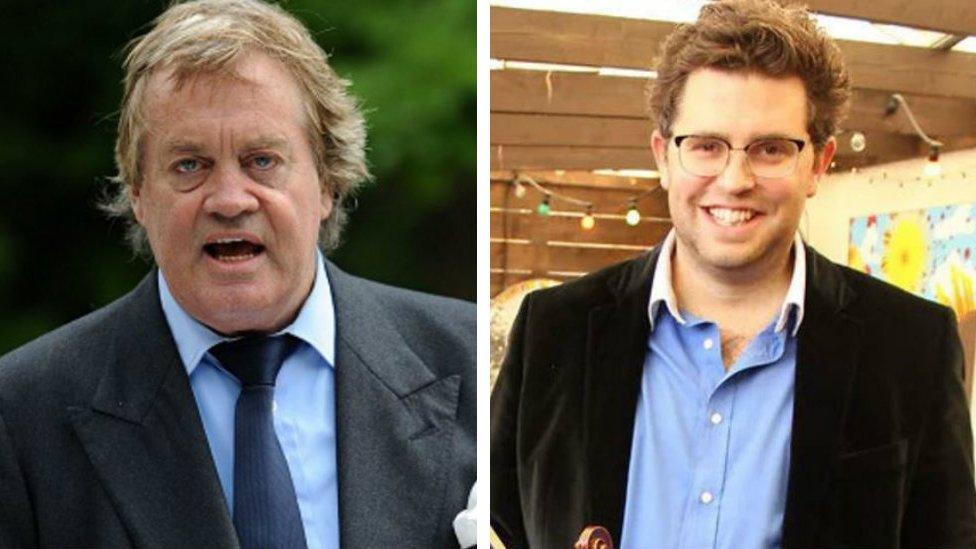

Alexander Wood (right) tried to impersonate the 12th Duke of Marlborough to avoid paying for hotels and bar tabs in Kensington and Mayfair

A conman who posed as the Duke of Marlborough and racked up bills of more than £10,000 in luxury hotels has been jailed for three and a half years. As audacious as his lies might sound, Alexander Wood is certainly not the first high-profile conman to adopt an aristocratic alter-ego.

If Wood's case sounds familiar, it might be because it echoes the plot of Fawlty Towers' first-ever episode, where a fraudster posing as one Lord Melbury tries to hoodwink hotel manager Basil Fawlty.

The high-class guest is later revealed to be a trickster pulling off a scam, attempting to steal Basil's collection of valuable coins.

Wood, in a similar fashion, blagged his way into some of London's top hotels by pretending to be a senior member of British Airways staff and, on one occasion, the Duke of Marlborough.

He booked into the Great North Hotel under the duke's name, Jamie Spencer, in May this year and set up an agreement where he would be allowed to spend £100 a day on "incidentals" such as meals and taxis, which would be added to the bill.

A conman who claimed to be called Lord Melbury formed part of proceedings of the first-ever episode of BBC One comedy Fawlty Towers

Staff smelled a rat when the "duke" started exceeding the limit and spending money on drinks for fellow guests.

When he was confronted, Wood pretended to have left his identification in his room and tried to flee the hotel without paying.

A child prodigy, international violin soloist Wood, from Southend, Essex, had gone on to set up a successful business and had grown accustomed to a lavish lifestyle.

He resorted to extreme measures in order to - in the words of his defence barrister - "live up to a status he didn't really have".

But his is not the only real-life example of a conman getting ideas above his station, and adopting an upper-class persona.

Perkin Warbeck's attempt to pass himself off as the Duke of York was not a great success - he was hanged in 1499

Posing as an aristocrat, or even royalty, has long been a tactic employed by those seeking to extort money or gain a higher status.

In 1495, a man called Perkin Warbeck claimed to be the Duke of York and went on to lead an unsuccessful rebellion against King Henry VII.

After confessing he was an imposter, he was hanged in 1499.

Although the punishments might not be so extreme nowadays, the audacity of the impersonators has not lessened.

A Facebook user pretended to be Prince Harry and told a workman he wanted new floors in Buckingham Palace

Last year, a Facebook user posing as Prince Harry conned a floor fitter out of thousands of euros.

The fake prince offered the Austrian workman a million-euro contract to renovate the parquet flooring at Buckingham Palace.

The victim transferred 27,500 euros (£23,000) to several UK bank accounts but never heard back from the "prince", who has yet to be tracked down.

But that amount is nothing compared to what a former Manchester United boss lost to an "aristocrat".

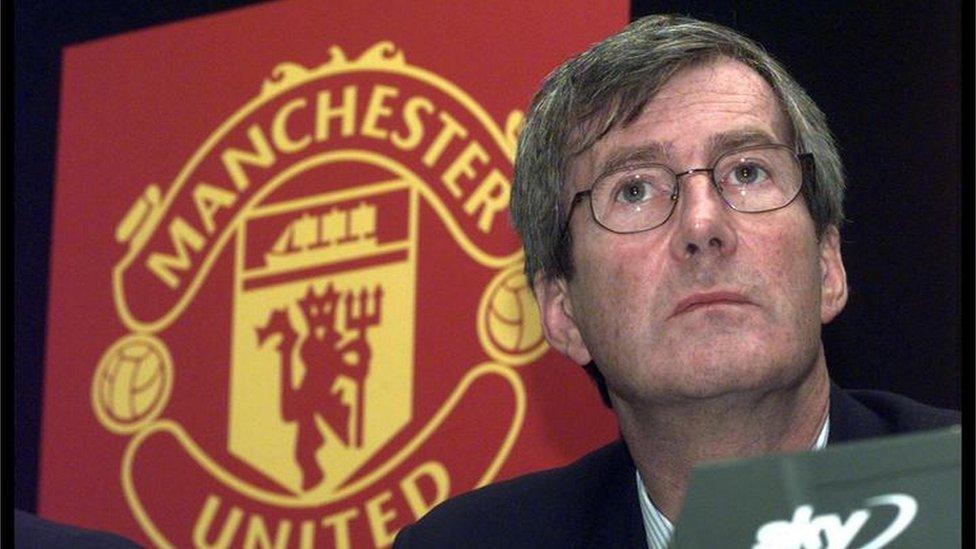

Former Manchester United boss Martin Edwards lost an estimated £7m to a conman who claimed to have royal connections

Former club chairman and chief executive Martin Edwards said he lost millions to a man called Michael Brown, who posed as a bond dealer and aristocrat.

Brown, who had claimed connections with royalty, was on the run in 2008 when he was convicted in his absence of stealing $8.5m (£5.2m).

He was arrested in the Dominican Republic in early 2012, and is now serving a seven-year sentence.

Conning clients and business associates out of money is one thing - but what about those who take in friends and family with their flights of fancy?

Conman Scott Travis pretended he played drums for the band Whitesnake. Pictured is one of their actual drummers, Cozy Powell

In 2012, the Daily Mail, external reported the case of Scott Travis, who falsely claimed he was he was Viscount Franco Dibella III, a playboy millionaire Italian aristocrat, before he was jailed for eight years in 2012.

He told people - including his own girlfriend and her elderly father - he stood to inherit £1.7m, and claimed he used to play drums for the rock band Whitesnake.

The paper said Travis, from Manchester, obtained credit cards, loans and mobile phones in other people's names to rip off a string of victims.

He bought a £50,000 Lexus and employed his own chauffeur, the Mail said.

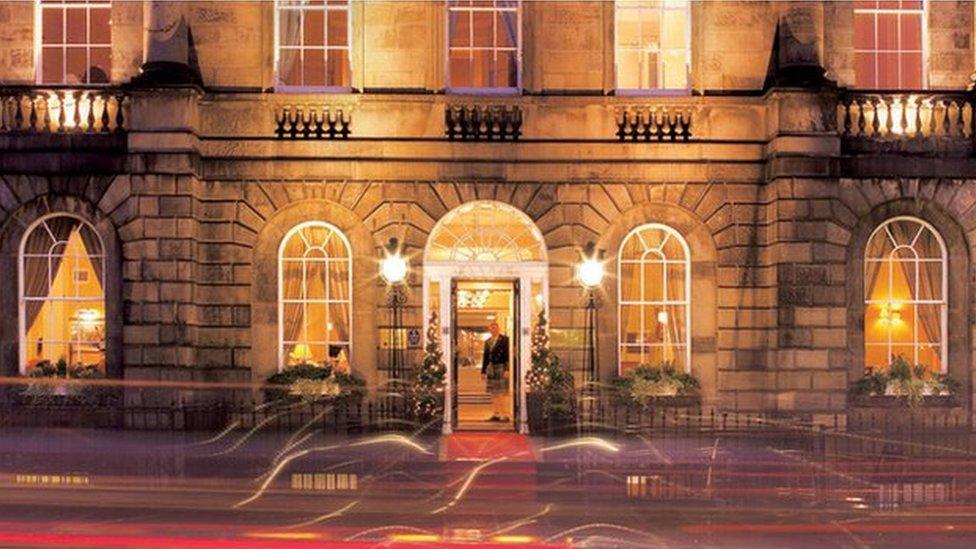

Fake viscount Kirk Brown stayed at the luxury Roxburghe Hotel in Edinburgh as part of his scam

Another fake viscount spun a tall tale which involved him claiming to be a successful author.

The Evening Standard, external ran a story in 2013 about Kirk Brown, of Farnham, Surrey, who pretended to be a viscount and conned his mother-in-law Nicola Young out of £150,000.

He changed his name by deed poll to Vizconde von Hoehen de Bessarabia and claimed to own a non-existent shipping firm.

Ms Young told the Standard how Brown had been staying at a luxury Edinburgh hotel when he enlisted Location, Location, Location's Phil Spencer to find him a house in London.

Brown claimed he had written a debut novel which was going to be made into a film. He was eventually jailed for 40 months.

Pretend duke Alexander Wood has been jailed for three and a half years

But what makes people assume an upper-class identity in a bid to defraud others?

"They just want to make money and have a good life without having to work for it," said chartered psychologist Clive Sims.

The web of lies woven by those who seek to con others can often become more and more complicated and last for many years, he said, something he puts down to "simple reinforcement".

"You do something, it works, therefore you do it again. If you stop, you'll be caught out in a lie and that would puncture the illusion," he said.

Mr Sims said anyone setting up a con which involved interacting with people "had to be a good actor".

"For someone to aim to obtain money and good by deception, they have to immerse themselves into the persona - it's an actor's mask."