Charles Fryatt: The man executed for ramming a U-Boat

- Published

Charles Fryatt's story was told in a range of publications, from newspapers to comics

The name Charles Fryatt is memorialised from New Zealand to Canada. Yet he was tried, convicted and executed as a "terrorist". A century on, Captain Fryatt's case is still debated by legal experts. But why would a merchant ship's commander ever try ramming a U-boat?

"I don't think he set out to be a hero," says Louise Gill. "I think he set out to look after his crew, his men and women, and trying to avoid capture."

Gill is the great-granddaughter of Fryatt who, in March 1915, attempted to ram a prowling German U-boat with his 1902-built passenger ferry, the Great Eastern Railway-owned SS Brussels.

Ordered to stop by submarine U-33 near the Maas lightvessel off the Dutch coast, Fryatt - born in Southampton and raised in Harwich - saw the German U-boat surface.

It was his third such encounter with a U-boat that month.

Believing it was being readied to torpedo his ship, Fryatt ordered full steam ahead and tried to ram the U-boat head on, forcing it to crash-dive.

The SS Brussels managed to escape and Fryatt was awarded a gold watch by the Admiralty.

Louise Gill says she is hugely proud of the actions of her great-grandfather

But 15 months later his ship was cornered by five German destroyers shortly after setting sail from the Hook of Holland. Fryatt, his crew and passengers were taken to an internment camp near Berlin.

Fryatt was then taken away to Bruges to stand trial on charges of being franc-tireur - a civilian engaged in hostile military activity.

His gold watch from the Admiralty was used as evidence against him and he was accused of sinking the German submarine - despite U-33 still being in active service.

The hearing, sentence and execution by firing squad all took place on the same day, 27 July.

Captain Charles Fryatt: The man executed for ramming a U-boat

Fryatt had earlier told his captors he had done his duty to protect his crew but, according to press reports at the time, was not allowed to speak at his trial.

His death was to have propaganda value for both sides, says Mark Baker, a Fryatt memorabilia collector who is organising an exhibition commemorating the centenary of his execution.

For the Germans, the execution of Fryatt was a case of justice served.

For the British, says Baker, Fryatt's execution was both an outrage and a useful springboard for recruitment and swaying international opinion against Germany.

"In 1916," he says, "people were starting to become a bit war weary and recruitment had become conscription.

"His death came at the right time for the government which used the case of Fryatt to show how ghastly the 'Hun' were."

The name "Fryatt" was also written on shells fired at the Germans.

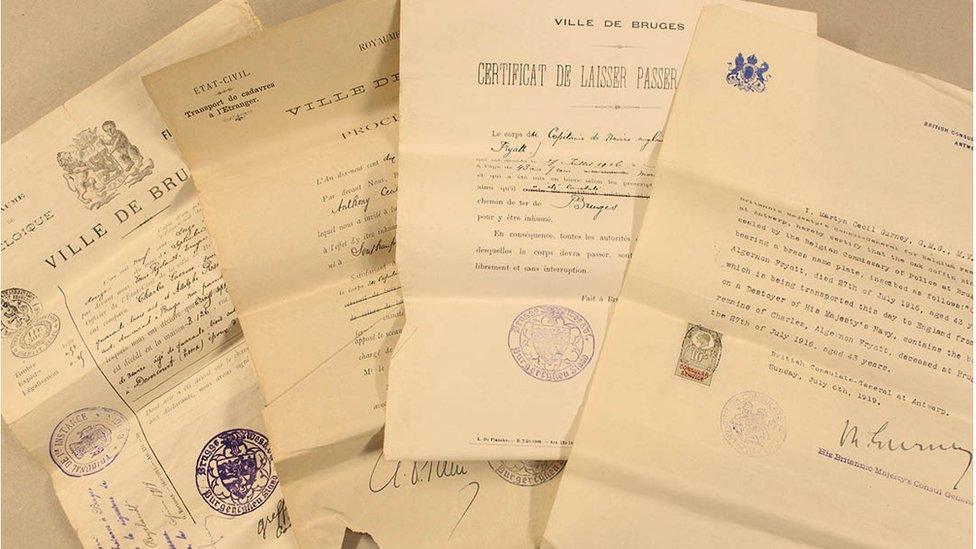

Papers relating to the case of Captain Fryatt

The Fryatt case was also seized upon by Irish nationalists who accused the British government of hypocrisy.

If the British government was outraged at the execution of a civilian committing an act of war, the nationalists argued, how could they condone such executions in Ireland?

The U-boat threat

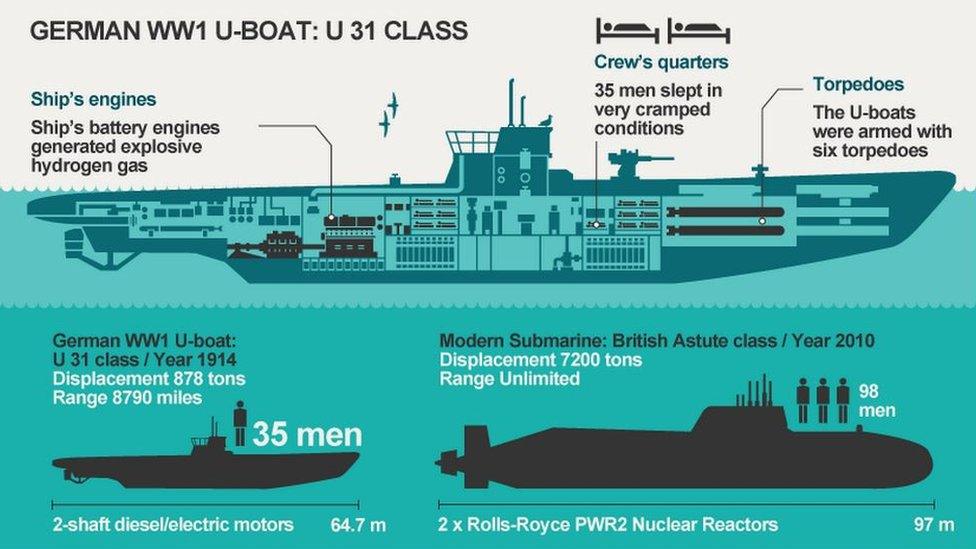

The men on board U-31 would have lived in very cramped conditions

The name U-boat comes from Unterseeboot (undersea boat). Early U-boats were designed to protect German ports and harbours

U-boats tended to leave port on the surface at night and only submerged when spotted by the enemy, or after conducting an attack

Once submerged, the electric batteries posed a real explosion threat to the crew

They were turned against merchant ships supplying Britain in February 1915 in retaliation for an increasingly tight British blockade preventing ships carrying vital supplies from reaching Germany

The U-boats' most notable victim was the liner Lusitania, sunk by U-20 on 7 May 1915; this caused the loss of 1,201 lives

Mr Baker, whose exhibition takes place at the Masonic Hall in Harwich (where Fryatt himself was once a member), said: "I find the story itself fascinating,

"Though sometimes the way it is told on websites is as if he was the only person who had ever rammed a U-boat.

"U-boat ramming was actually common practice following an instruction from the Admiralty that crews should attempt to ram U-boats.

"The objective, however, wasn't to actually hit the U-boats," says Baker, "because merchant ships were usually fairly fragile.

"The actual objective was to make the submarines dive."

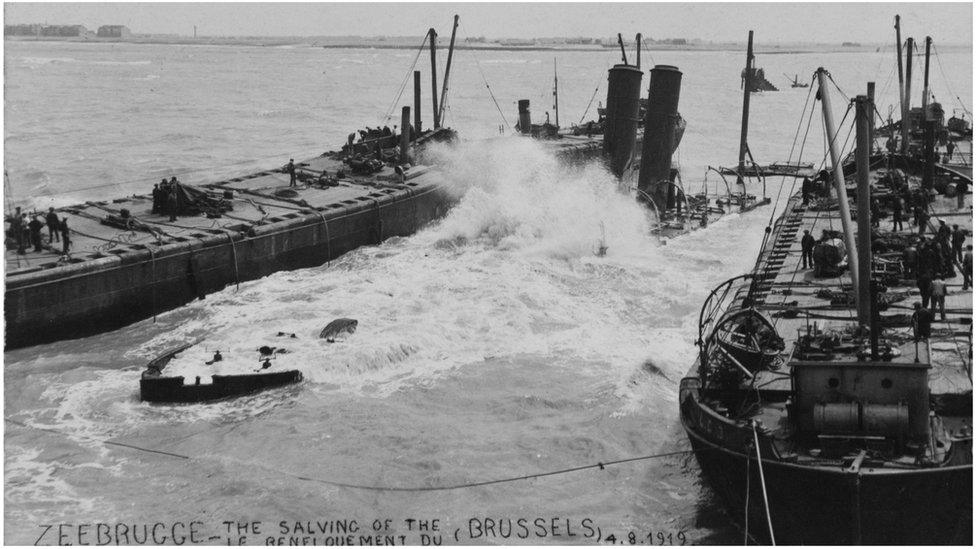

The SS Brussels was scuttled after Fryatt's capture

There were four reasons for this, Baker says.

The first is that a submerged U-boat could not pull up alongside a merchant ship and board it.

Nor could a submerged submarine use its deck guns.

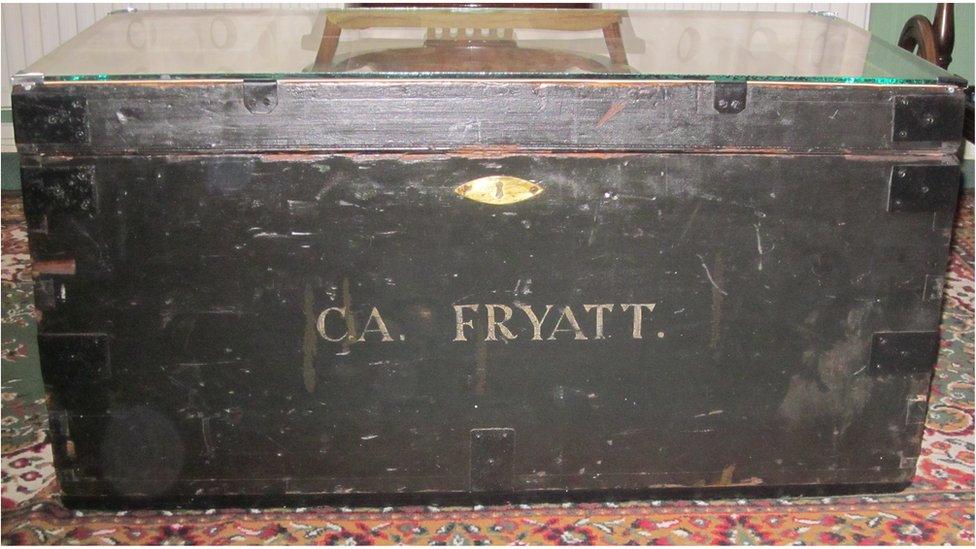

Some of the items going on show at a special exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of the death of Charles Fryatt

Fryatt's trunk had been used by a lady in Harwich for storing bedding before it was bought by a collector

Thirdly, submarines were slower underwater which gave shipping an advantage in terms of getting away.

Finally, torpedoes were notoriously unreliable and inaccurate and, given a beam view of a ship rather than a broadside, a merchant ship's chances of getting away unscathed were vastly improved.

Fifteen months after he tried to ram the U-boat, Fryatt's ship was cornered by five gunboats and he was imprisoned.

"He was tried in Bruges on charges of being franc-tireur - a terrorist - for a civilian act of war, and he was executed for being a terrorist.

"It is still very, very controversial," said Baker. "It's a case that has exercised legal minds ever since.

"Merchant mariners' rights to defend themselves in open water is still very much a grey area."

The SS Brussels

One of the lesser known effects of the Fryatt case, says Gill, was the fear it instilled in his widow Ethel.

"They were not allowed to talk about the case and even after the war," says Gill, "her children (of which there were six) were not to take the name Fryatt."

The reason? Widow Fryatt had an uncanny grasp of future history.

"It was in case there was another war with Germany," Gill explains.

"If they won and invaded she feared they would track down the Fryatt family members."

So today, the relations that bear Fryatt's name are not his direct descendants but those of his siblings, many of whom still live in the Southampton area.

Mr Baker's exhibition takes place at the Masonic Hall, Ferndale Road, Harwich, from 23 July to 31 July

- Published21 January 2016