Inside the school where 98% of the pupils are travellers

- Published

For years there were no children from the settled community at Crays Hill Primary. Now, there are two.

At the edge of an Essex village sits a primary school unlike any other in the UK. Only a handful of its children will ever go on to secondary school and some of the pupils will disappear for weeks or months at a time. Yet hardly anybody wants to talk about it. Why?

For decades the primary school in Crays Hill was at the heart of village life.

Then came Dale Farm, which grew to become Europe's largest traveller site. Increasing numbers of children from the site - some of it legally developed, some of it illegally - joined the school.

The shifting pupil mix came to a head in 2004, when the then head teacher and 10 members of the governing body quit amid concerns at falling pupil numbers and how the school would fare in the future.

It was also the year children from settled families evaporated. Completely.

Head teacher Hayley Dyer says politics about her school remains strictly outside the gates

By the end of 2004, not a single child from the settled community of Crays Hill was left. All pupils were from traveller families.

Today, the school is still going and going strong, according to Ofsted, which just a few months ago praised the "good quality of education" offered by this "well-organised and welcoming school".

And yet barely anybody seems to want to talk about this village school.

At least in public.

Crays Hill Primary in numbers

There were 52 pupils on the roll when the BBC visited

In 2014-15, 15 fixed-term exclusions were recorded

The school will get an extra £73,920 this year in pupil premium, external payments, which is additional funding for schools aimed at raising the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. Seventy-five per cent of Crays Hill pupils are eligible for the premium compared with a national primary school average of about 25%

In 2015-16 the unauthorised absence rate was 17.6%. A decade ago it was 24.2%. The national school average is 1.1%.

All four members of the local parish council - including a former governor at the school - were asked about the school. None responded.

Former parents - including one of the last to remove her children from the school back in 2004 - would not speak about it either. One, whose children are now teenagers, told the BBC she felt there were "more important issues" in the community.

Emma Nuttall, advice and policy manager for the Traveller-support charity Friends, Families and Travellers, said the school and its population were the victims of "prejudice".

"There will be others in similar situations," she said. "Would they dare to raise the issue if the majority of the pupils were Asian or black? I think not."

But in Crays Hill there are strong feelings on both sides.

Not a single traveller parent would allow their child to talk about their school on camera or allow their children's faces to be photographed. The reason, it appears, were concerns of a backlash against their families amid a row nearby over illegal development at the nearby Hovefield site.

The walls of Cray's Hill are full of the children's artwork and projects which range from outer space to ancient history to this series of self-portraits

Yet beyond this apparent wall of silence lies a hive of activity, in which children are children and teachers face a daily juggling act they say is pretty much unlike anything else in the English education system.

In one class you will find children reading, drawing and doing craft work. In another, you might find children studying classical mythology.

Tasked with inventing their own creatures, one girl had come up with a half man/half snake monster. But she laughed at her own creation when she realised a snake with legs closely resembled a lizard or a dinosaur.

"I think I might start again," she joked.

She is one of 52 pupils currently on the school roll.

Fifty are from traveller families. That two pupils are from the settled community is in itself a significant change.

For head teacher Hayley Dyer, any politics surrounding her school remains strictly outside the green iron gates.

Her role, and that of her staff, is to do their best for any child who comes through the doors.

Yes, she is aware of how her school is perceived by some.

"There have been some people who had a particular view of the school and who have had a particular view of some of our children," she says.

And she is a realist about the concerns any settled family might have about enrolling their child at her school.

"The mix is so small," she says. "But if more parents came and more children came, that mix would be better and which would in turn lessen the need for those considerations."

Mrs Dyer, who joined as deputy head nine years ago, is equally upfront about the particular challenges her staff face.

Some pupils can disappear for a week, a month or a year at a time.

Fluctuating headcounts make planning the school finances, which are based on headcounts (census days) taken on a single day three times a year, a little tricky.

"Looking forward into the future is very difficult. The biggest absence, I think, has been for two years. They had been abroad."

Crays Hill is not a school that suits all teachers.

While finding the school provided a "good quality of education", Ofsted also noted in its January report, external that "a new deputy head teacher was appointed and has since left" and told how "four teachers have left and three have joined the school".

"It is either a job you thrive in or you think 'it is not for me'," says Mrs Dyer. "People will very quickly decide which one they are when they start teaching."

It is also a school where very few children at Crays Hill will go on to secondary education.

That situation was made worse last year after one of Crays Hill's top former pupils was killed on the A127.

Joseph Sheridan, 13, was walking across the dual carriageway when he was hit by a BMW which had no time to stop.

Referring to him as "our Joseph", Mrs Dyer said: "He had been with us from age four until 11 and was doing great in secondary school (at the nearby The Bromfords School).

"He was such an ambassador for his community."

The impact of his death on the travelling community was that "everybody felt they had to hold on tighter to their children".

It was not the first difficult time for the school.

Young travellers from Dale Farm at Crays Hill, Essex protest over the threat of eviction from their site outside Basildon Town Hall in 2005

The evictions of 80 traveller families from their illegally-built homes at Dale Farm five years ago was a period of "high anxiety" for the school community.

The leadership provided by the then head teacher Sulan Goodwin was nothing short of "amazing", says Mrs Dyer,

"It was a difficult time for staff knowing that some of their children were affected.

"What we tried to do was to continue with normal school.

"There was high anxiety at that time and it was definitely difficult.

"We wanted to make sure there was some firm ground beneath their feet. It was really important."

The school lost a number of children following the evictions and so the roll numbers today do not justify single year groups.

Instead, the population is divided into three - foundation and year ones, year twos, threes and fours and then a final class grouping of years five and six. This distillation of the population leaves an eerie silence hanging over the unused rooms of the school, which was built, in the early 20th Century, to house more than 150 pupils.

The school day starts with early-morning activities, such as reading or doing jigsaws and, once the actual school day starts, pupils do 15 minutes of focused reading followed by 15 minutes of handwriting.

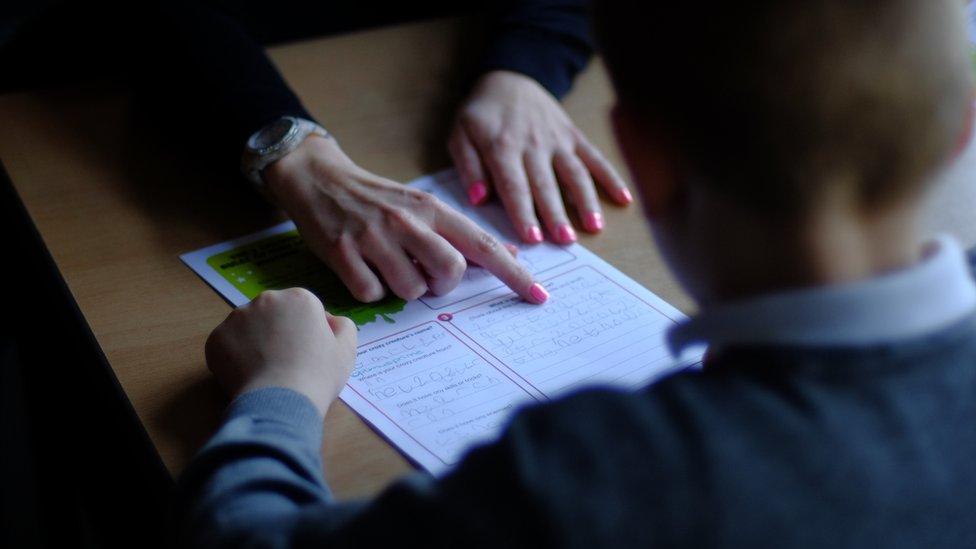

For the rest of the morning, children then move into other groups, sorted not by age but by reading ability.

It means pupils get more relevant teaching.

Malcolm Buckley, the former leader of Basildon Council and who currently serves as a county councillor for the area, wants families from the settled community to see what Crays Hill has to offer.

And he believes a rebalancing of the traveller and settled community at Crays Hill is inevitable.

"We have extreme pressure on primary school places in Basildon so the schools which have places in them will have to be used," he said.

"The other thing is that the school has been classified as a good school and (settled) parents can have much more confidence in it than they appear to have."

He said he understood community reluctance surrounding the school because "you only get one shot at a child's education" and "if you get it wrong" it can have a "lasting impact".

The school's growing relationship with the wider community, which includes a number of external groups using the premises, is vital, he said.

And although the parish council would not discuss its proposals to resume holding its meetings at the school, Mr Buckley said that was something he would like to see.

"When those organisations use the school, actually see it inside and see how it operates, it instils confidence."

This is music to the ears of Phien O'Reachtigan of the National Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Council, who says what happened at the school in 2004 was "terrible" and a "disgrace".

Mr O'Reachtigan believes reintegration will benefit all concerned.

"Children are not naturally prejudiced," he said. "They inherit prejudice from their parents. What happened in 2004 was a terrible situation, there was no reason for parents to take their children away.

"Friendships were broken when the children were taken away and it has had a lasting impact."

Asked what success looks like at a school like Crays Hill, Mrs Dyer ponders for a while.

A positive Ofsted report is useful, she says, for the school's relationship with the outside world.

But within the school, success is more personal. One of the eight pupils taking part in a dance session is a boy called Richard.

Watching him dance makes Mrs Dyer smile.

"Sometimes it spoils his afternoon so it is good to see him enjoying it," she says.

This kind of small triumph, along with improvements in reading or writing, or examples of excellent behaviour, are what success looks like at Crays Hill to Mrs Dyer.

"It is those individual achievements that are most precious."

- Published19 October 2016