Grace Millane murder: A trial that gripped a nation

- Published

Grace Millane was last seen alive on the eve of her 22nd birthday

Guilty. The intake of breath, a sob from the dead woman's mother. A single word was all it took to bring to an end one of the most highly publicised murder cases in New Zealand's history.

Three weeks of evidence, hundreds of hours of painstaking police work and a year of grief for a family had built up to the moment 12 jurors agreed that a 27-year-old man had murdered Grace Millane.

What had started out as a missing person inquiry in December 2018 when a daughter, sister and friend failed to respond to 22nd birthday messages swiftly turned into a murder investigation.

When Ms Millane did not respond to birthday messages, her family issued an appeal on social media

Within days of her disappearance, police had identified a suspect, spoken to him and, unbeknownst to the killer, tracked his movements by trawling through CCTV evidence.

Before long police would find Ms Millane's body, which he had stuffed into a suitcase and buried in the mountainous Waitākere Ranges. There followed an outpouring of grief from a small nation unused to such crimes.

The backpacker's body was discovered in bushland outside Auckland

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern issued an apology to Ms Millane's parents David and Gillian, saying "your daughter should have been safe here, she wasn't and I'm sorry for that".

Ms Millane, from Wickford, Essex, and the man who would go on to murder her made contact through a dating app and hit it off immediately.

She was in Auckland as part of a round-the-world trip, while he had been living there working in various sales jobs.

It was clear from the footage they enjoyed each other's company; they were close, they kissed. Ms Millane even messaged a friend back home to tell her how much she was connecting with him.

The pair were seen getting on well at various locations in the city

They returned to his hotel.

But after she left the lift, she was never seen alive again.

They were seen in a lift, heading for the room where Ms Millane would be murdered

There he strangled her before taking pictures of her and watching pornography. He claimed she had died accidentally during consensual sex.

Despite his murder conviction, her killer still cannot be named. A court suppression order remains in place and is likely to do so beyond his sentencing on 21 February, in part because of the level of interest in the case.

Reporting on the trial has proved challenging; because the defendant could not be named, CCTV footage had to be blurred, and there were legal disputes over some pieces of evidence. Several witnesses also had their identities protected.

The killer's identity is suppressed under New Zealand law

Because of the nature of the killer's defence, Ms Millane's parents have had to listen to claims about their daughter's sex life, with the details reported across New Zealand and around the world.

Graphic information, in particular regarding the night of her murder, was analysed as Mr and Mrs Millane watched in court.

At times, Mrs Millane would look at the floor or hold her head in her hands as the injuries inflicted on her daughter were described.

The University of Lincoln graduate was on a round-the-world trip at the time of her death

The prosecution accused the man of "eroticising" Ms Millane's death by taking intimate photographs of her body and looking up pornography while she lay dead in his room.

In a way, he managed to do the same during her trial with his story about consensual sex gone wrong - a tale rejected by the jury - leading to a focus on BDSM and breath-play.

Experts, Tinder dates and ex-lovers were all brought to court to talk about the killer and his victim.

The defendant was portrayed as a serial dater; he even messaged and met up with a woman as Ms Millane's body lay in a suitcase.

It was the sexualising of the murder that brought the killer down.

The timeline of his Google searches and the naked pictures of Ms Millane were irreconcilable with his case, the prosecution said. Either Ms Millane was dead when they were taken, or he had searched for the Waitākere Ranges, where he buried her body, while she was still living - thus showing he planned to kill her.

The defence could only offer that they had been "random" drunk searches, and the Waitākere Ranges was perhaps somewhere the pair had planned to go for a day out.

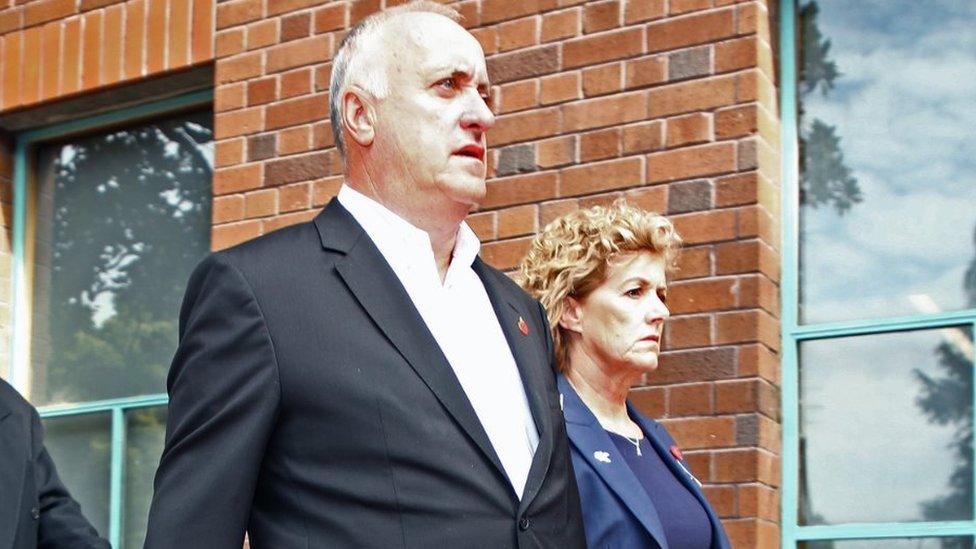

David and Gillian Millane attended the trial in Auckland

The killer's right to use the "rough sex" defence, and some of the reporting of it, has angered Fiona Mackenzie, founder of the campaign group We Can't Consent To This.

Describing it as the "ultimate victim blaming", she said: "He gets to tell her story, he gets to tell the story of what she was like and how she asked for it.

"Families not only lose their loved one but these men [those who use such a defence] steal the public perception of them and destroy their reputation. It's appalling."