Coronavirus: How are hospices coping during the pandemic?

- Published

The St Helena Hospice in Colchester looks after those with incurable illnesses

They care for dying patients in their final days, but having to shut their charity shops and cancel fundraising events has put UK hospices in financial peril. How is the coronavirus pandemic affecting their staff and the families of the dying?

Once upon a time - say, two weeks ago - families could arrive en-masse to visit a dying loved one.

But stringent restrictions are now in place here at St Helena Hospice, in Colchester.

Each patient can now only have one visitor at a time.

If more than one relative arrives, they must observe a one-in-one-out system, with the other visitors having to wait outside the main building.

And elderly visitors, unless they are next-of-kin, are being asked not to visit at all.

Even the hospice's chief executive is currently barred from the in-patient ward.

On Monday night, 82-year-old Patricia Pelham died here.

Her daughter, Louisa Brewster, believes her mother waited until after her last visit before she did.

Louisa Brewster and her mother Patricia on her 82nd birthday last August

Diagnosed with cancer in January, Mrs Pelham - a once-expert jive dancer and a lover of family, laughter and Elton John - spent her last five weeks at St Helena.

Her daughter, a former nurse, saw first hand the change in infection control measures being introduced at the hospice.

"Five weeks ago the world was a very different place," says Mrs Brewster. "You could go in whenever you wanted, with whoever you wanted.

"I wanted everybody to see mum - siblings, cousins - we had plans for all of mum's friends to visit."

First came the hand sanitiser stations, then the restricted visiting hours, then the markers on the floor to guide social distancing, she says.

Staff here are having to restrict entry to one visitor per patient at a time

"When you were really upset, nobody could cuddle you. That was the hardest thing, I think, and then came the one visitor rule."

Mrs Pelham's friends, because of their age, could no longer visit.

"Then it was just me, as next of kin. It was very lonely and nobody could cuddle me.

"I understand all of the measures as an ex-nurse, and I know it was very tough for the staff."

Yet for all of the restrictions in place, Mrs Brewster remains hugely grateful for everything the hospice did in her mother's final weeks.

"Mum had what I could call a really good death. The staff were absolutely amazing - it felt like you were leaving her with family, really.

"They have made life and death so much easier."

What are hospices?

The aim of hospice care is to improve the lives of people with an incurable illness.

Across the UK there are more than 200 hospices.

Together, they care for more than 200,000 adults and children each year.

According to the NHS, external, hospices aim to "feel more like a home than hospitals do".

"We are in uncertain days," says the matron, Sue O'Neill.

There's the faintest hint of a smile accompanying her words. She knows it is an understatement.

Sue O'Neill, the matron at St Helena Hospice in Colchester, says coronavirus restrictions have been hard on everyone

Like all hospices, about two-thirds of St Helena's income comes from its network of charity shops, fundraising events and donations from members of the public.

At present, all of its shops are closed and all charitable events are on hold.

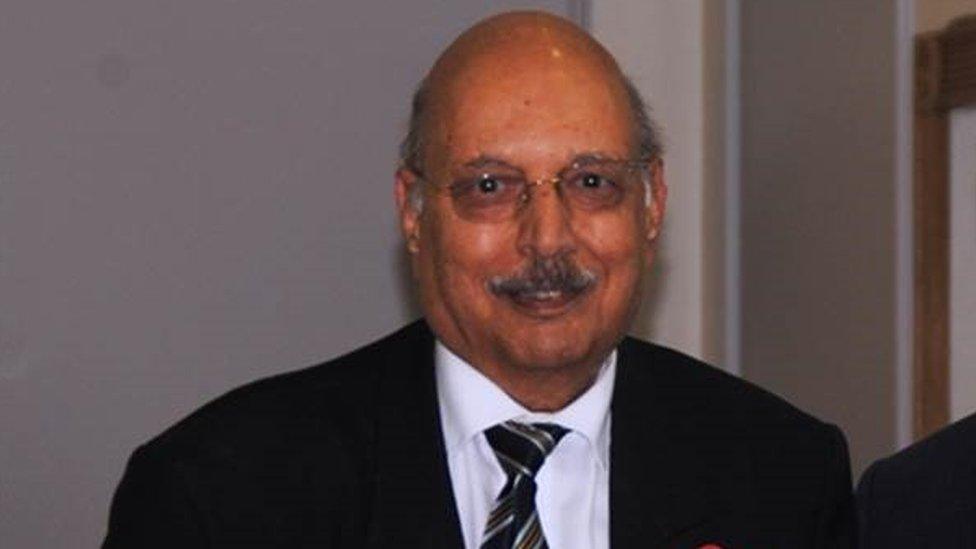

This, says hospice chief executive Mark Jarman-Howe, has had an "immediate and dramatic impact" on cash flow.

The situation is so bad, he says, that the hospice might have to scale back some of the care it delivers to thousands of people each year.

Already, the hospice's day therapy centres in Colchester and Clacton have been closed because of the coronavirus, while its bereavement and counselling support is currently being run by telephone rather than in person.

Chief executive Mark Jarman-Howe is not allowed on the wards under coronavirus restrictions

The current restrictions on visitors, says Mrs O'Neill, are "very hard" on patients and their families. But having to impose such draconian measures is also very hard on staff.

Social distancing rules have affected not just how staff can relate to patients and their families, but how staff relate to each other.

Conversations about a patient's treatment used to held between staff in hushed tones in a corridor.

Not now.

Such discussions now demand an element of planning. Colleagues need to find somewhere private and that lets them remain 2m (6ft) apart.

Remaining fit and able to come to work has also come at a cost to some hospice workers.

"We have staff self-isolating from their own children so that they can be at work," says Mrs O'Neill. "That's a huge sacrifice."

And amid the visiting restrictions, staff falling ill and the drop in income comes a fourth challenge - an increase in demand.

The hospice is expecting to take in a number of NHS patients in the weeks ahead, to ease the burden on hospitals.

Such patients - who are currently being identified by hospital staff - are likely to include people recovering from operations, those who have had a stroke or those who cannot recuperate at home, the hospice said.

The hospice dining area has been turned into an additional ward in anticipation of the incoming NHS patients and its 'virtual ward' - in which the hospice sends staff out to care for patients at home - has also been expanded.

"None of us have ever faced this before," says Jo Tonkin, director of care.

Jo Tonkin, director of care, says there is a small team at St Helena Hospice working with other hospices during the pandemic

Clinical staff have been asked to cancel their annual leave.

"We are expecting peak of activity around Easter," she says. "A number of staff are finding themselves working in completely different roles, with longer hours and different shift patterns.

"They know that they're needed, they know that they're valued."

Does she feel hospices are sometimes overlooked?

"There is that feeling," she says. "NHS staff do need all the help they can get during this time, but hospices are pooling their resources with each other, the NHS and others, to do our bit in this effort because we cannot do it on our own.

"We are small organisations with small teams. I do think that sometimes hospices are not heard in the big scheme of things."

In the past two weeks, the hospice's call centre has seen a significant rise in the number of calls from both patients and their families.

The hospice says they are becoming "progressively more distressed and concerned about their welfare" and about how they will be able to access services "with the lockdown in place".

The hospice is currently dealing with about 150 calls each day

Like all care services, the hospice also faces growing uncertainty over the availability of vital pieces of equipment.

Mr Jarman-Howe says they are just about managing in terms of protective equipment, such as goggles and face masks.

But he says he is concerned about the future availability of such equipment, and especially certain technical items such as the small battery-powered machines that gradually administer pain relief to patients, called syringe drivers.

And just as the BBC was leaving, we witnessed first hand the importance of hospices to those affected by them.

A man carrying a brown box walked into the hospice, emerging once again a few seconds later.

He was followed soon after by a female member of staff.

"I just wanted to say thank you so much for that," she says.

The man, Steve Wright, had just delivered a box full of protective masks.

Steve Wright, whose mother was previously in the hospice, delivered protective masks to the staff

Mr Wright, who runs an engineering company, seems a little embarrassed to be collared by a reporter while carrying out a small and quiet act of kindness.

Nine years ago his mother was a hospice patient. He heard the hospice was short of protective equipment and wanted them to have his own supply, and others he had managed to get from similar businesses in the town.

"We've all got to play our part, haven't we," he says.

- Published27 March 2020

- Published25 March 2020