Alphamstone: Were these ice age rocks an ancient sacred place?

- Published

Dr Canton with one of the sarsen stones around the church at Alphamstone

Next to the road outside St Barnabas Church in the village of Alphamstone, Essex, lay two lichen-mottled rocks - glacial erratics brought here during the last ice age thousands of years ago.

More of these sarsen stones can be found nearby. Two of them have become part of the fabric of the church itself. Outside, in the churchyard, some stones stand above the surface, while others rest below.

Although they do not form a circle, the dozen or so sarsen stones of Alphamstone, between Sudbury and Colchester, have been loosely grouped together. But why? And by who?

"The land here has been a sacred place for thousands of years," says Dr James Canton, who wrote 'Grounded: A Journey into the Landscapes of Ancestor' during the pandemic.

"Wherever you have humans and you have land, you will have these sacred spaces."

Dr Canton says he hopes "in this frenzy of the modern world" people will seek out places of "quiet reflection", which "can help them learn to slow down".

Just like the ancient forebears, farmers in Alphamstone have long needed to know exactly where the stones are (some are understood to be beneath the ground) in order to protect their farming machinery

And that, it seems, is exactly what the public at large is doing.

According to government figures, 45% of people spent more time outside in 2021-22 than they did the year before, external.

And their reasons for stepping outside their front doors are changing too.

In 2009-10, dog walking was the main reason people gave for visiting the natural environment. It has since been eclipsed by health and exercise.

Getting outdoors to "relax and unwind" is also becoming increasingly important - up from 26% in 2009-10 to 38% a decade later, external.

An interest in historic sites is also on the rise, with English Heritage recording record visitor numbers in 2022.

Psychologist Dr Kate Sparks says contemplative spaces, and being out in nature generally, "helps us relax, refresh and appreciate life".

"It is often a way of just switching off," she says. "Some people seek out the complete opposite - a busy coffee shop, for example, where the sheer amount of noise can help.

"Either way, it's a way of escaping."

St Barnabas Church in Alphamstone was built among some of the village's sarsen stones

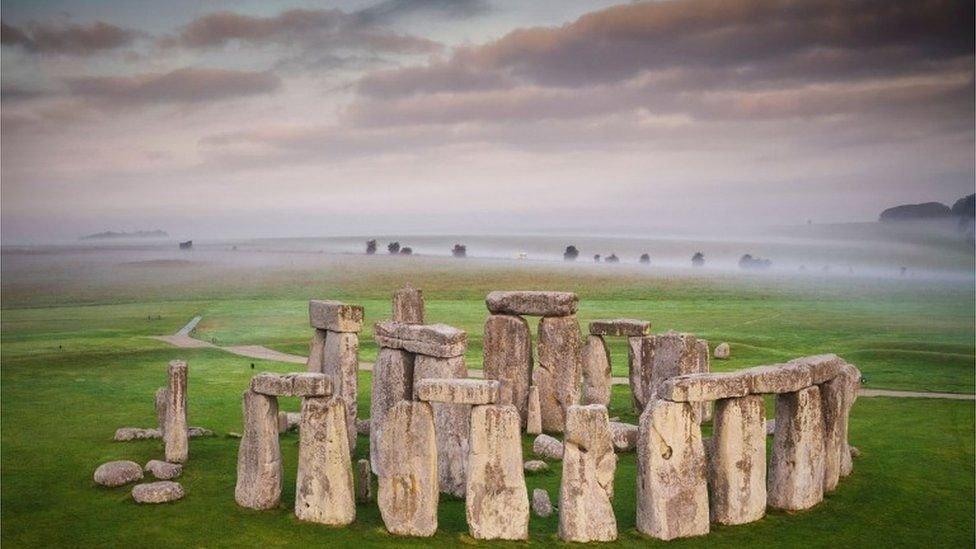

Shared spaces and experiences, such as visiting Stonehenge or a music concert, offer a heightened sense of well-being because humans are social creatures, she says.

Might such heightened, shared experiences of the past explain why communities agreed certain places and spaces were sacred?

Perhaps, says Dr Canton, the director of wild writing at Essex University and whose own interest in sacred places was sparked by visits to his local church.

Dr James Canton spent the coronavirus lockdowns working on a book about sacred places within the various landscapes of East Anglia

"The village I live in has a church and a curry house, so you can go for a curry and if you go for a walk, you go to the church," he says. "I would tend to go not to the church, but this little pathway at the back of the church.

"And that is where I would remember my dad, who died a long time ago. I was thinking, that's odd - why don't I just go to the church? Well, I'm not Christian, but I like going to churches.

"And I was thinking of Philip Larkin's poem 'Church Going' where he talks about stepping into spaces like this as a non-Christian and what he calls the 'tense, musty, unignorable silence' and that sense that you can have as a non-Christian person, that sense of the numinous, a sense of the sacred - and you can still feel it today."

Algae at Blick Mead in Wiltshire turns flint bright pink, researchers at the University of Buckingham found

Take the ancient spring in Blick Mead in Wiltshire, for example.

Evidence shows it was visited both by animals, such as aurochs (pre-domesticated cattle), and Mesolithic hunter gatherers, external thousands of years ago.

Recently named Archaeologist of the Year, external, Prof David Jacques, of the University of Buckingham, began leading excavations on the privately-owned Blick Mead site in 2005.

It is a place, he says, where you can sense its history and importance.

"There's an awareness that people were coming here from 8,000BC to about 3,500BC. It is such a vast period that spans Britain becoming Britain because it was once part of the continent," he says.

"And you ask yourself, what was it about this place that pulled people here? Like a lot of places of myth and ritual, the sense of the sacred often starts with the practical.

"It was a brilliant place for hunting large herbivores. And hunting those big animals was possibly like the FA Cup of its day."

Archaeologists have found offerings at Blick Mead that memorialised the hunting and the feasting, external that took place.

"They were left as a permanent record of events there and the people who left them would have known people had been coming before them."

It continues to be a special place, Prof Jacques says. "There is a Midwinter torch light walk here on Midwinter's Night. That was a local reaction to the site - it was a response to the site being special."

The votive offerings at Blick Mead fascinate Dr Canton.

"With springs comes a long continuity of dropping objects, or votive offerings, into them," he says, pointing to the mini-ritual of dropping coins and making wishes at fountains and wells, which continues to this day.

One of the most peculiar discoveries at Blick Mead is that flint dropped into its spring water turns bright pink.

"It is basically due to an algae that lives in the pool," says Dr Canton.

"But can you imagine what that was like for pre-historic people? That's magic."

Alas, Alphamstone's sarsen stones do not turn bright pink when it rains. But they do, its residents say, help define the village and continue to be a source of both pride and mystery.

Paul Gwynne has lived in Alphamstone for two decades

Gardener Paul Gwynne, who has lived in the village for 20 years, says: "People refer to them in conversation and talk about them when they talk about the history of Alphamstone."

The stones were most likely moved from fields by the region's earliest farmers, keen to avoid damaging their equipment.

But they were not just moved to the side of a field and left there.

The sheer effort involved in grouping them together, says Dr Canton, strongly suggests it was deliberate. And, given Bronze Age burial urns have been found nearby, it suggests this was a place of spiritual importance.

The inclusion of two stones in the very fabric of the church building also has the current residents of Alphamstone intrigued.

"We are still trying to understand them at the layman's level," says Mr Gwynne. "There's a gathering of them in the churchyard and a couple of them are incorporated into the foundations of the church.

"Why? And why not the rest of them? And that leads you to think they must have had some spiritual or ritual significance.

"Even if they don't really have a lot of meaning in their daily lives, people here are quite protective of them.

"They are also a source of pride, given that they appear to be a gathering of sarsen stones which is unique here in East Anglia."

Photography by Laurence Cawley, unless otherwise stated.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published12 August 2022

- Published28 April 2022

- Published2 March 2022

- Published13 November 2020