The 'formidable' Essex architect behind school concrete crisis

- Published

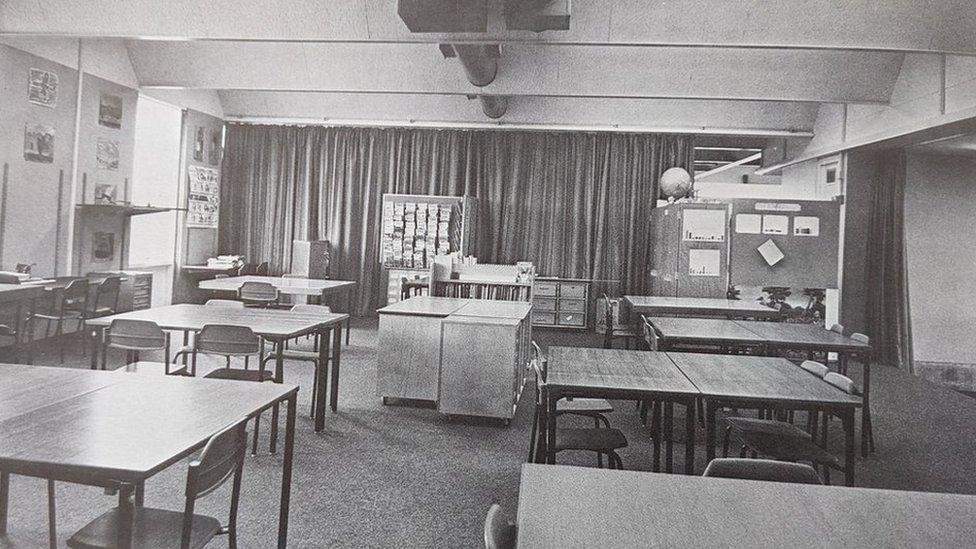

Elmstead Primary School, pictured in a 1974 brochure from the Essex County Council architect's department, is one of the schools affected by the Raac crisis

The concrete crisis affecting schools in Essex can be traced back to a "formidable" architect in the 1970s, research by the BBC has found.

Ralph Crowe and his team at Essex County Council designed a relatively cheap building system using reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac).

A former colleague says he protested directly to Mr Crowe at the time over the risks of using Raac.

At least 54 Essex schools contain Raac, making it the worst affected county.

Nationwide, the government published an official list of 147 schools affected by the potentially unsafe concrete - with the schools having a delayed or disrupted start to the new term.

The government has previously said the high concentration of Raac in Essex was a result of post-war building and population increase.

But Max Haigh, who worked for Mr Crowe as an architectural technician in the 1970s, says the architect's determination to use Raac is the reason for the crisis in Essex.

"It was a quick fix for getting the amount of schools built that we needed," said Mr Haigh.

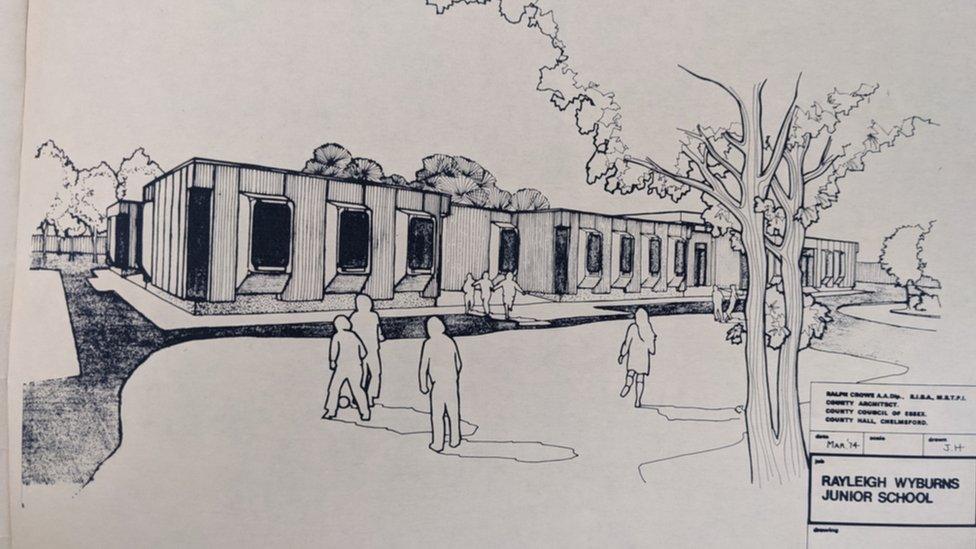

Wyburns Primary School in Rayleigh, as sketched out in March 1974, is also one of the schools today affected by Raac

Mr Crowe, who died in 1990, was the county architect for Essex between 1966 and 1976, a powerful role at the time.

He led and championed the development of mostly single-storey modular component building (MCB), which contained Raac roof panels.

"I suggested doing a steel pan roof, with a reinforced concrete fill, but that was poo poohed because it was too expensive - they couldn't afford it," Mr Haigh said.

A total of 42 MCB primary schools were built in Essex between 1973-1980, and a further eight by 1990, according to research published by Essex County Council architect Christopher French, external.

They included Anglo European School in Ingatestone, Elmstead Primary School near Colchester, Barnes Farm Junior School in Chelmsford and Thameside Primary School in Grays - all buildings affected by the Raac crisis.

Parents of children at Buckhurst Community School gathered last week to protest over the Raac crisis

Mr Haigh said he "hated" MCB schools.

"I said I had concerns with this 'concrete cancer' and if a roof leaks, the water will get into the aerated concrete and it will freeze, swell up and blow," he said.

"These concrete panels were only on a steel beam with about a 100mm to 150mm bearing, and if the end bearing goes, the whole panel could come down.

"It's always been in the back of my mind and all of a sudden it's come up big time, hasn't it?"

Mr Haigh, who went on to work in the private sector and retired 13 years ago, said of Mr Crowe: "He was pompous; whatever he says goes."

Jodie, pictured with all her four children, has to do three different school runs as a result of Raac-caused disruption in Mistley, Essex

Mr French wrote that Mr Crowe's "preoccupation" with MCB and his "abrasive personality, led to many clashes" with colleagues and he left Essex "under a cloud" to take up a teaching post at the University of Newcastle.

The council and Education Secretary Gillian Keegan have explained the Essex proliferation of Raac as the result of a post-war population boom and the construction of new towns like Harlow and Basildon.

While the number of school age children was increasing in Essex - with 12,000 more added to the register in September 1973 and 850 new teachers hired that month - this rationale appears over simplified.

Essex needed to create 10,000 new school places in 1973-74, with a £6.1m capital spending budget, and Mr French wrote that limited funds from central government at the time were felt "acutely" in the county.

In a newsletter written by Mr Crowe in 1974, seen by the BBC, he said MCB was "cheaper" and would "reduce maintenance costs".

It was a "philosophy of building", he wrote.

Watch: How Raac can crumble under pressure

Mr Crowe also wanted a more environmentally efficient design, off the back of an oil crisis, and he said MCB would "reduce solar gain in summer and fuel consumption in winter".

Essex was part of a cluster of county architects in the south east, all following similar designs, but Mr Crowe withdrew from the consortium in 1974 to turbo charge the MCB programme.

John Hare was a technical inspector for that regional consortium in the 1970s and he remembered Mr Crowe splintering off.

"Ralph was a formidable character and had considerable influence within the council," Mr Hare told the BBC.

Before moving to Essex, Mr Crowe designed Shirehall in Shrewsbury - opened by Queen Elizabeth II - which has been celebrated as a "remarkable space" and a "major monument to post-war modernism".

Education secretary Gillian Keegan said unsafe concrete in schools would be sorted

David Robertson, a civil and structural engineer, who contributed to a Raac study group for the Institution of Structural Engineers, said these county architects typically "imposed their views" on their departments.

"County architects are very much a thing of the past and it's very different in the political systems of today," said Mr Robertson.

"Some of them would have very much ruled the roost."

In a statement, Essex County Council once again highlighted the expansion of new towns following World War Two.

A spokesperson said: "The use of Raac in public buildings is not unique to Essex and during the post-war period, Raac was a building material which was widely being used in the construction of public sector buildings across the country.

"This is because it was known for providing value for money for taxpayers."

The Department for Education declined to comment.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

- Published10 September 2023

- Published8 September 2023

- Published7 September 2023

- Published13 February 2024

- Published5 September 2023

- Published5 September 2023

- Published1 September 2023