D-Day: Ex-BBC man Trevor Hill recalls Eisenhower speech

- Published

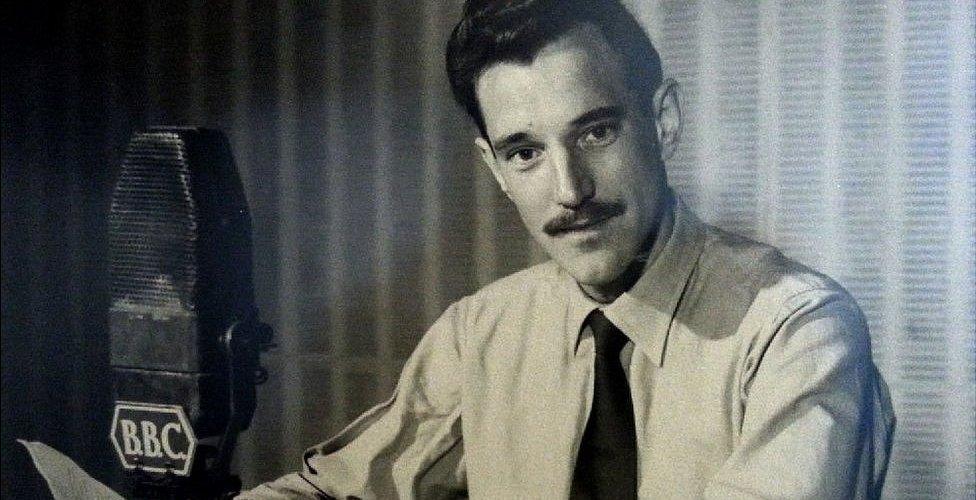

Trevor Hill went on to become a BBC announcer after working as a studio manager during World War Two

On 6 June 1944, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower broadcast a message to the people of Western Europe informing them the D-Day landings had started. But before most people heard his words, an 18-year-old BBC studio manager at the BBC in London was let in on the secret.

Trevor Hill was tasked with playing out the recording of the now famous speech. Because his duties involved having to listen to recordings prior to their transmission, he knew that D-Day was happening before almost any other member of the public.

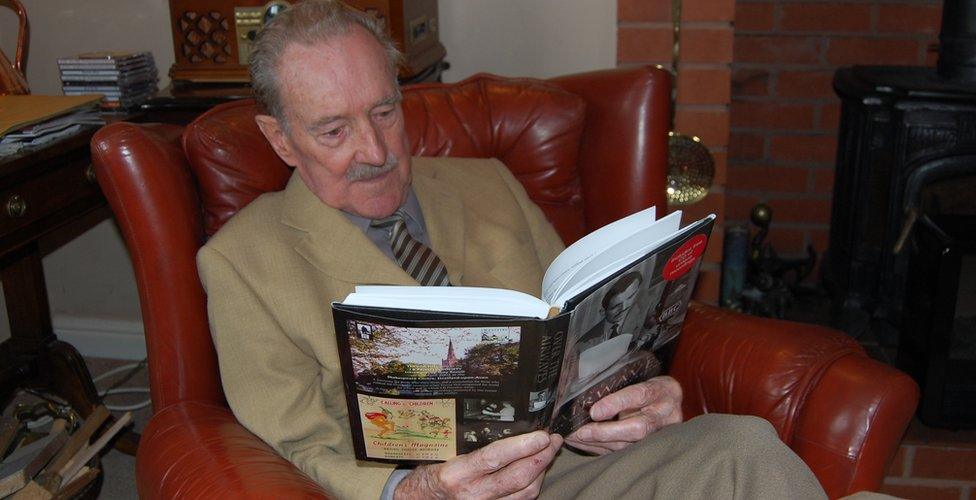

Now, aged 88, on the eve of that 70th anniversary, he recalls the momentous events of 6 June 1944 from his home near Dursley, Gloucestershire.

"I took the acetate disc, plonked it on the turntable, lowered the pickup, and heard this voice... I thought, 'Wow'," he said.

General Eisenhower told the people of Western Europe about the D-Day invasion in a speech on 6 June 1944.

The disc had been sent by dispatch rider from Bushy Park, home of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, where General Eisenhower was based, to the BBC Overseas Service studio at 200 Oxford Street - Broadcasting House had been bombed earlier in the war.

"When I opened the package, to my amazement this acetate disc didn't say 'BBC', it said 'AFRS', which turned out to be 'Armed Forces Radio Service'."

After he heard what was on the recording, he had to keep its contents to himself.

"I wasn't allowed to ring my mother and let her know I wouldn't be home. I wasn't allowed to speak to anybody," he said.

"When I wanted to go up one floor to go to the loo, two MI5 officers came into the loo with me.

"We waited and waited, and then (BBC announcer) John Snagge turned up.

"He then introduced Eisenhower. Three and a half hours since I'd heard him announce D-Day, it was then broadcast.

"What an incredible day it was."

Operation Neptune - the start of Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of north west Europe - had been many months in the planning.

On D-Day, the first day of the attack, about 156,000 Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy in the largest amphibious assault in history.

It is considered by many to have been a turning point in World War Two.

Now 88, Trevor Hill lives near Dursley in Gloucestershire

The plan had been kept secret from the Germans, who thought an attack would happen further up the coast at Calais.

General Eisenhower's announcement to the citizens of Western Europe that the invasion had begun was the first the public knew of the invasion.

Mr Hill took the disc of the recording home after he was told initially the BBC's recordings library was not interested in it and could not take it "because it was not a BBC recording".

But later he did hand it back. Had he kept hold of it he could have made a small fortune - in the 1990s he was offered £30,000 for the original disc by a group of Americans.

Simon Rooks, head of archive policy at BBC Archives, said the current whereabouts of the original AFRS disc was unknown.

"I've seen no evidence that it was ever kept," he said. "The likely explanation is that the BBC made a recording of it on its own systems.

"A permanent pressing in the form of a 78 rpm disc would have been made, and later copies on celluloid and quarter-inch tape.

"The important thing is a recording of it was kept."

So 70 years on, how does Mr Hill feel about being part of one of the most significant moments in the history of broadcasting?

"I know what a wonderful, wonderful moment it was to hear Eisenhower's announcement," he said.

"But one realised very, very soon that it was all going on at a great cost to mankind and the families of those who perished."