Southampton's lost Titanic generation

- Published

Titanic's lost crew members are remembered at Southampton's Old Cemetery

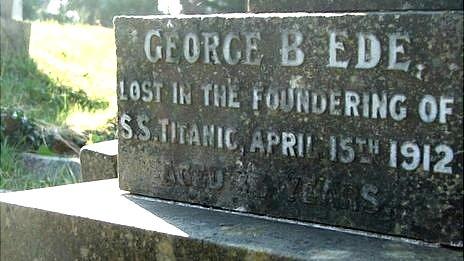

Forty-four worn and weathered headstones stand in Southampton's Old Cemetery - but there are no graves underneath.

They bear the names of residents who died when the Titanic sank after hitting an iceberg in April 1912.

For some, families could not afford to repatriate the bodies of their loved ones. Others were lost at sea.

Even though 100 years have passed, fresh flowers are still laid every year.

More than 540 people from the city perished in the disaster.

Cemetery volunteer Gillie Dunkason said: "In Southampton we commemorate rather than celebrate Titanic.

"There was so much hardship and then so much excitement to get a job on Titanic, [only] for it to come to this bitter end. They were just ordinary people."

Hottest ticket

Among the names on the headstones are those of Arthur May, 60, and his 23-year-old son, also called Arthur. The Titanic journey was the first time they had worked at sea together.

Between them they left two widows and 11 children.

The scale of the loss for Southampton was almost on a par with the Blitz, when 630 people died, and was felt for generations.

Crowds gathered in Southampton to await the return of Titanic survivors

At Northam School, near the docks, 120 out of 250 pupils lost their father.

A century on, throughout the city there are still individual memorials to victims - engineers, musicians, postal workers - and buildings intimately linked to the events of April 1912.

A coal strike that year had left thousands out of work in Southampton, so when the world's most luxurious liner began recruiting crew on Saturday 6 April, it was the hottest ticket in town.

Titanic's arrival also meant a boom for local firms. Oatley and Watling supplied fresh fruit and vegetables and FG Bealing's vast nursery at Highfield provided 400 plants for the ship and buttonhole flowers for every first-class passenger.

Desperate for news

While first-class passengers stayed at the luxurious South Western Hotel before their transatlantic departure, many of the "below decks" crew - boiler room stokers, trimmers and greasers - lived in poor conditions in the Old Town areas of Northam, Chapel and St Mary's.

Captain Edward Smith lived in an imposing six bedroom house on Winn Road.

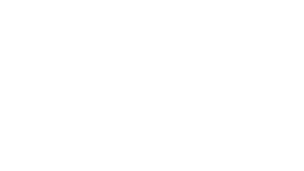

Walter Fredericks and Fred Fleet survived the ordeal

Many stewards and officers lived in the new suburbs of Freemantle and Shirley. In one street alone - Malmesbury Road - all eight men who went to sea perished.

More than 720 of Titanic's 900-strong crew were from Southampton and all but three were men. Only 124 returned to the city.

Men were drawn to Southampton docks from around the country.

They included Jack Dawson - a former soldier from Dublin who was lodging with his friend's mother at 17 Briton Street, and whose name was used for Leonardo di Caprio's character in the 1997 Hollywood blockbuster Titanic.

Rumours that the "unsinkable" Titanic had gone down first reached Southampton early on Monday 15 April as radio telegraph messages spread between ships in the Atlantic.

Distressed family members gathered at the White Star Line offices in Canute Road, desperate for news.

But it took several days for the survivors to be taken to New York and for the list to be sent back to the UK. Even then, the first-class passengers' details were sent back first.

'Taboo subject'

Historian Jake Simpkin, who leads tours of Southampton's Titanic sites, said: "For that week flags flew at half mast, the papers were full of obituary notices and Southampton was at the centre of world attention - it was very sad."

The Northam Girls' School log for 15 April reads: "A great many girls are absent this afternoon owing to the sad news regarding the Titanic, fathers and brothers are on the vessel and some of the little ones have been in tears all afternoon."

With so many breadwinners lost, hundreds of families faced being plunged into poverty.

Most seamen had no kind of insurance, their employment only lasted as long as they were on board ship. Some employment records even show dead crew as being "discharged at sea".

With the Titanic disaster dominating front pages around the world, donations for a relief fund for families flooded in. Payments continued until as late as 1994.

Mr Simpkin said: "You can never replace the loss of a husband but many of the widows and children suddenly found they had a dependable income for the first time in their lives and apprenticeships for their children paid for from the fund. Some of the children did quite well in life."

Dave Fredericks, from Southampton, has researched the experiences of his great-grandfather Walter Fredericks, a trimmer who escaped in one of the last lifeboats on what was his 21st birthday.

Eight men from Malmesbury Road were among the 549 from Southampton lost when Titanic sank

He said: "Some [survivors] went straight back on the ships, that's how they dealt with it. Walter had a young family so when things got tight again, he had no choice but to go back to sea."

While the financial consequences could be dealt with, the emotional scars ran deeper.

Many survivors struggled to come to terms with the fact they had lived while so many had perished.

Mr Simpkin recalls living near Fred Fleet, Titanic's lookout, in Freemantle. He suffered from flashbacks and later took his own life in 1965 following the death of his wife.

Mr Simpkin said: "I would love to have spoken to him but in Southampton, when I grew up, it was a taboo subject - no-one would talk about it.

"It's very sad, we should remember it with quiet reflection - it still hits a nerve with people in Southampton.

"We never want to to lose sight of the fact that it was a disaster when all these people died, but it's easy to overlook that sometimes."