Hovercraft capsize disaster off Hampshire coast recalled 50 years on

- Published

Helicopters, rescue boats and navy divers were involved in the efforts to save those on board

Fifty years ago, a passenger hovercraft with 27 people on board capsized in gale force winds on the Solent off the Hampshire coast. It was the first fatal accident involving hovercraft travel - then in its formative years and still heralded as the brave new face of transport.

Five people on the Hovertravel SRN6-012, travelling from Ryde on the Isle of Wight to Southsea, died in the tragedy - including seven-year-old Julie O'Connell and 48-year-old David Jones whose body was never recovered.

Memories of the disaster have faded over five decades, but for those involved, the events of 4 March 1972 remain vivid.

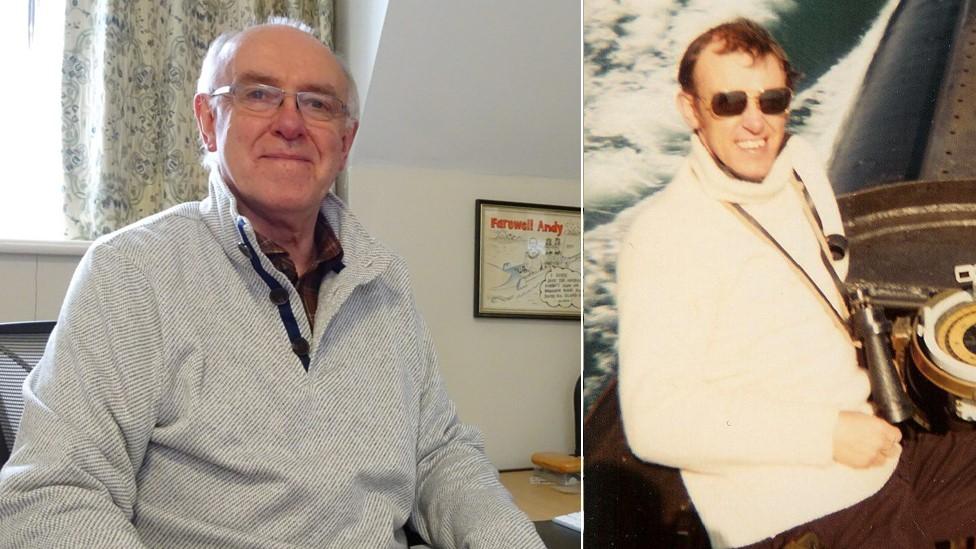

Andy Benford remembers "ghastly" weather which meant he returned to the mainland on an earlier crossing

Earlier that day, Andy Benford, then a 21-year old Royal Navy sub-lieutenant, had taken his first flight on a hovercraft, crossing from Portsmouth for a daytrip on the Isle of Wight with his brother Tim, a 27-year-old flight lieutenant in the RAF.

A few weeks before, he had been sent on a helicopter dunking course, to learn how to survive ditching in the sea - it was to prove "fortuitous" timing.

He remembers "ghastly" weather spoiling their day on the island and the pair making the fateful decision to return to the mainland on an earlier-than-planned crossing.

The flight from Ryde would ordinarily only take about nine minutes, but the pilot had reduced speed because of winds in the Solent gusting up to 50 knots.

About 400 yards (360m) from Southsea Pier, disaster struck.

The accident was caused by an unusual combination of wind and wave conditions at sea

"I could see the pilot in the cockpit struggling to keep on track. Then there was an almighty shudder as we dug into the wave," recalled Andy.

"The sea rose up on the windows and there was another judder, then a really bad thump and, very slowly, it went over on the port side."

His brother Tim saw "huge, boiling waves ahead of us" at the harbour entrance shortly before the capsize.

"There was considerable commotion and I was aware that the hovercraft floor was now the ceiling," he said.

'Standing on the water'

With seawater fast filling the compartment, a number of regular passengers apparently knew to push out the windows in an emergency.

The brothers threw a bench seat out the craft to give themselves something to hold on to when they got out.

But, while Tim made it out, swam under the hovercraft skirt and bobbed up, as Andy went to follow, the vessel capsized completely, throwing him back inside.

He said: "I retreated into the darkness of an air-pocket by the window up to my waist in water.

"I could make out the sea-green opening of the window, took a deep breath, ducked down, and swam out without touching the sides - to exactly where Tim was sitting on the hull."

Relieved to be reunited, Tim recalled: "We sat there together totally drenched watching the waves and feeling the gale force winds."

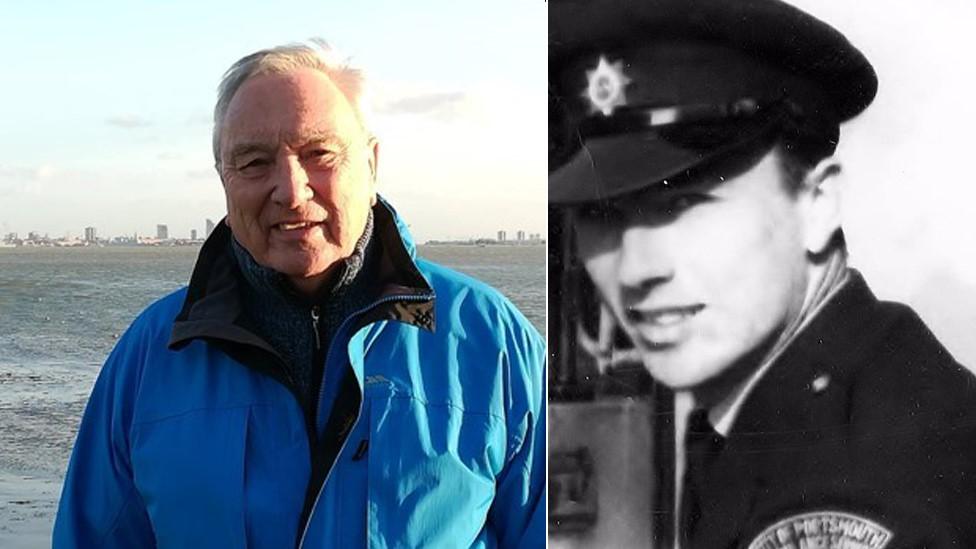

Auxiliary coastguard John Andrews witnessed the hovercraft capsize

On the shore, auxiliary coastguard John Andrews was parked at Southsea and saw the disaster unfold and immediately raised the alarm.

He later told a BBC television news reporter: "I saw her slow right down, the wind was very, very strong and she suddenly dipped on a very peculiar swell, went right down on her side.

"The next thing she had flipped right up and then rolled right over."

Being so close to Portsmouth's naval base, rescue helicopters, a fleet of navy and civilian boats as well as military divers were quickly on the scene.

On the upturned hull, Tim and Andy waited with about 14 other passengers for help to arrive.

"We watched an RAF helicopter arrive and take the women off the craft and fly them to shore," recalled Tim.

'Wasn't your fault'

"The men were asked to wait to be picked up by a coastguard cutter. So we huddled together for about half an hour until one arrived and were taken back to Southsea beach."

Andy said: "I don't recall any panic or anyone calling out for help - it was all rather matter of fact and over very quickly, and the response by the rescue boats matched that speed - we were lucky to be so close to the harbour entrance.

"I didn't know that people hadn't survived until I saw it in the newspaper reports."

Five passengers were not as lucky - the disaster claimed the lives of Julie O'Connell, aged seven, and Charles Street, 45, from Portsmouth, Anne Robinson, 58, of Rogate, Sussex, and Audrey Jones, 47 of Redhill, Surrey.

The body of Audrey's husband, David Jones, was never recovered.

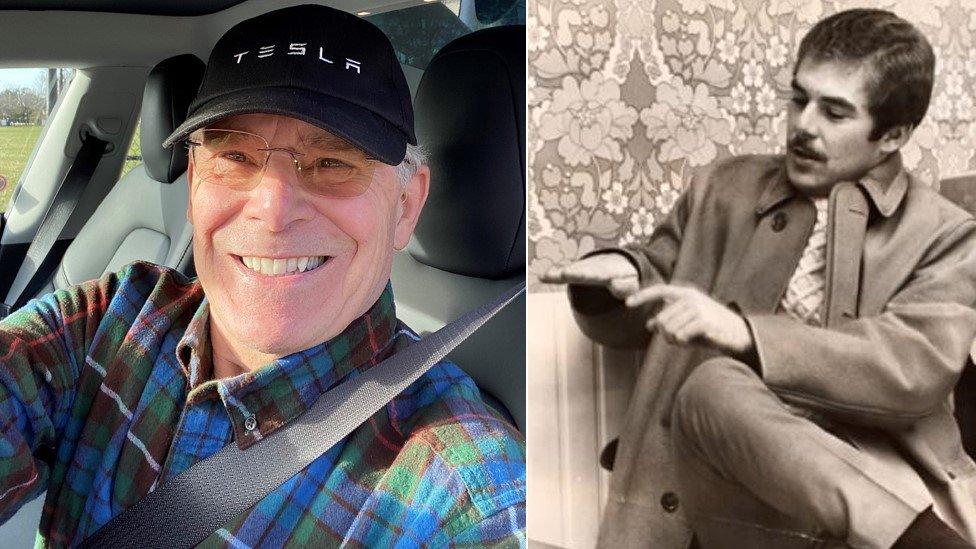

Graham Alland, also seen here in his early years in the ambulance service, helped treat the pilot

Among the first emergency services personnel who rushed to Southsea was ambulanceman Graham Alland.

Now 78, he recalled it as one of the stand-out events in his 32 years with the ambulance service.

He said: "When we arrived the rain was pouring down and it was blowing a gale and at first there was no sign of the hovercraft, then we saw a helicopter go over.

"All we could see from the beach was a group of people some way out to sea that looked like they were standing on the water - as the hovercraft was flat underneath.

"We immediately called for back-up but at the time there was nothing we could do until the helicopters and small craft were able to rescue them and bring them ashore."

Hundreds of people formed a human chain to haul the crippled hovercraft ashore

He helped treat the pilot Anthony Course who had suffered a gash to his forehead.

"He was still in shock, and saying that it happened so quickly. We were telling him 'it wasn't your fault'. He was so worried," he recalled.

The hovercraft eventually sank and a human chain formed to haul it ashore.

After being taken to hospital, Andy Benford had an X-ray on his hand and missed a police roll call.

It meant the brothers' parents, at home in Warwickshire, were visited by police officers informing them that Tim was alive and well, but there was no news of Andy.

In an era before mobile phones, they were only reassured when they saw Tim interviewed on that night's television news.

Hovercraft travel

The Hovertravel Express cross-Solent service began in 1965

British inventor Christopher Cockerell first demonstrated the principle of hovercraft travel in the early 1950s

A working prototype was ready by 1955, which Cockerell called the "hovercraft", obtaining a patent the following year

A cushion of air is created by a large fan underneath and a "skirt" surrounding the craft prevents too much air from escaping

As the craft is moving through air rather than water, it can go faster than a conventional boat of similar power

In June 1962 shipbuilder Vickers launched the UK's first commercial hovercraft service across the estuary of the River Dee between Liverpool and North Wales

Larger craft capable of carrying cars began operating across the English Channel but were forced into retirement at the start of the 21st Century by competition from the Channel Tunnel and the new breed of superferries

While hovercraft are still used for military and search-and-rescue purposes, the Ryde-Southsea crossing is thought to be the last remaining passenger service in western Europe

Despite making headlines around the world at the time, the disaster has faded from memory and much of the remembrance has been in private.

Historian Richard M Jones researched it for his 2016 book Capsized in the Solent and described it as a "forgotten" tragedy.

"It was a nightmare situation - a freak accident," he said.

"No-one could have predicted the tide and wind changes when the wind caught it and flipped it - it was quite a unique event.

"It was only the sheer bravery and the skills of the emergency services that prevented an even bigger catastrophe.

"The heroic actions of pilot Anthony Course and the quick rescue of survivors is something that should never be forgotten."

Survivors were winched from the upturned hovercraft

Speaking in the House of Commons the following week, Isle of Wight MP Mark Woodnutt paid tribute to the "quiet calm, courage and skill" of the rescuers.

"I know I am expressing the view of all the people of the Isle of Wight, who feel most unhappy that this tragedy should have occurred to a craft of which they are justly proud.

"We must not let this tragedy, sad though it is, obscure the wonderful record and future potential of this craft," he said.

The official inquiry found the capsize was caused by the "unusual combination of circumstances", with no blame attached to the pilot, operator or manufacturer.

'Vivid recall'

Pilot Anthony Course was praised at the inquest into the five deaths for his actions in staying with the craft until the last passenger had been winched to safety.

Aerospace minister Michael Heseltine, subsequently announced commercial hovercraft would have "mandatory upper wind and sea limits" in which they could operate.

Hovercraft went on to enjoy a good safety record - the next major fatal incident was not until 1985 when four people died when the SRN4 Princess Margaret crashed into the sea wall at Dover during a storm.

Hovertravel, which still operates the Ryde-Southsea service, said it would be marking the 50th anniversary within the company with a wreath-laying at sea to "acknowledge both those lost and the bravery of the rescuers".

Tim Benford, who now lives in the US, said he was "incredibly lucky to have escaped and survived"

Managing director Neil Chapman said: "As time passes, so that day in 1972 grows more distant but please be assured we fully appreciate the importance of the memory to all those who were involved and our thoughts are with the families of the bereaved and the survivors at this time.

"We use our own history and other incidents at sea as part of our ongoing safety training procedures for all our staff, ensuring that our operation continues to meet the exacting standards required."

Andy Benford went on to become a submarine commander in a 25-year career in the Royal Navy, but still has a "vivid recall" of the events of 50 years ago.

"I do think, 'what if If that day had gone differently?' Once I became a husband and father, I thought how horrendous it would be to be in that situation."

He admitted that for years afterwards he would always refuse to change his travel arrangements, as he had done on that wet afternoon on the Isle of Wight.

His brother Tim, who now lives in Dayton, Ohio, said: "We were incredibly lucky to have escaped and survived.

"It's appropriate to remember those who perished and to celebrate the subsequent safety record of passenger hovercraft."

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published4 March 2022

- Published1 October 2010