Castlemorton Common: The rave that changed the law

- Published

Ravers knew they could 'just turn up' to the festivals held by New Age Travellers

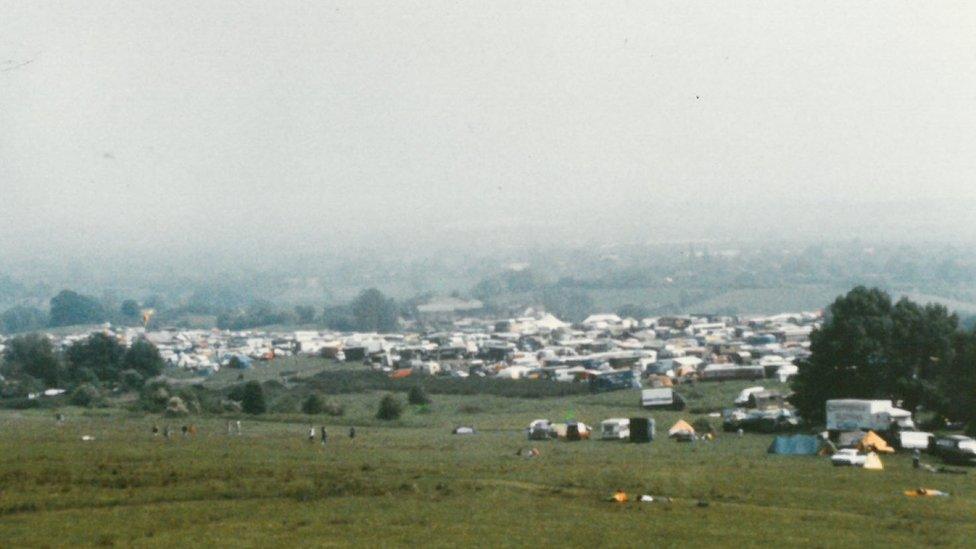

On a hot bank holiday weekend 25 years ago, 20,000 people descended on land in the shadow of the Malvern Hills. The word was spread by an answering machine message: "Right, listen up revellers. It's happening now and for the rest of the weekend, so get yourself out of the house and on to Castlemorton Common... Be there, all weekend, hardcore."

To say the event spiralled out of control is an understatement.

What started out as a small free festival for travellers not only went down in history as the biggest illegal rave ever held in the UK, but resulted in a trial costing £4m and the passing of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act.

The resulting publicity also had drastic consequences for the "alternative" lifestyle of the so-called New Age Travellers who started the event and for the underground rave movement who gate-crashed it.

Thousands of people heard about the event through word-of-mouth, media coverage and the infamous telephone message

The travelling community had been intent on holding the latest in a series of small events, having successfully held the so-called Avon Free Festival at Inglestone Common in Gloucestershire in the 1980s and early 90s.

In the weeks leading up to that fateful May bank holiday in 1992, they had tried and failed to stage festivals in both counties and in Somerset, where the police had repeatedly moved them on.

Retreating, they considered their options in a lay-by on the A38 in Gloucestershire, where it was decided to take their 10-mile long convoy out of the county, into Worcestershire and on to Castlemorton Common, near Malvern.

Libby Spragg was in one of the first vehicles to arrive at the site on the 22 May.

The 24-year-old joined the New Age Travellers in 1987 and had been to previous events across the West Country, including Inglestone.

She said the festivals were a chance "for networking, finding new work opportunities and just meeting friends that you couldn't really see at any other time", after a winter spent living and working on farms.

"Ingleston Common [had] one small stage, no dance music, and was part of the small free festival scene that had been bubbling along since the 60s."

The answering machine message that started the Castlemorton Common rave

Castlemorton should have continued that theme, she said, a low-key gathering for roughly 400 travellers.

What they hadn't banked on was the thousands of people who had heard about the event through word-of-mouth, media coverage and the infamous telephone message.

Carl Hendrickse, whose band Back to the Planet played at the festival, said a large number of people had been regularly travelling up and down the M25 to raves.

"People were not being given the right to gather," he explained.

"There were no facilities for people to come and dance, gather with like-minded people, and that is why they started happening illegally, because there were no proper facilities for people to have these kind of events."

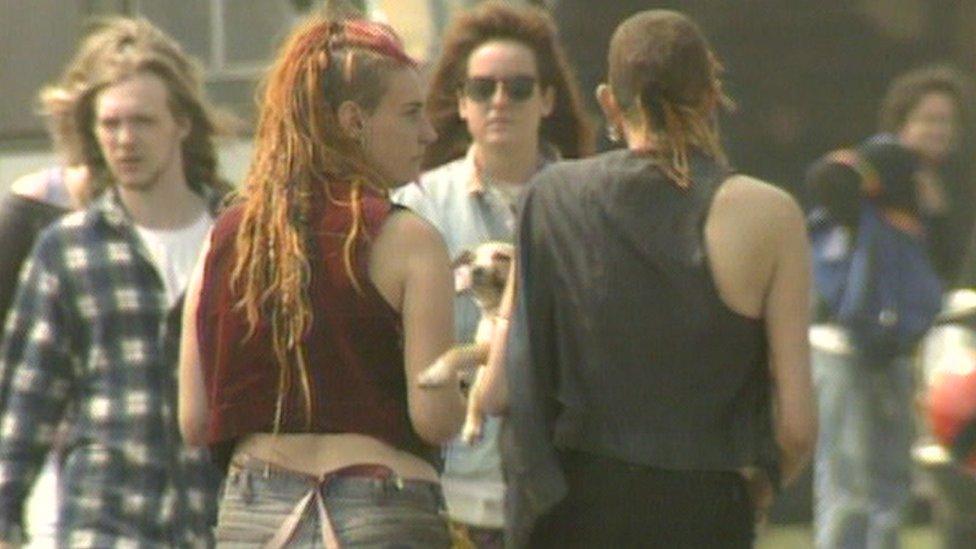

New Age Traveller Libby Spragg was interviewed by TV on her way to the site

Carl Loben, editor of DJ magazine, said in a world before mobile phones, the answering machine messages were key to spreading word about the raves.

"There was often just a message left on a party [phone] line that people could call after a certain time in the evening," he said.

"And it would say the rave is at [some location], meet at [this] junction of the motorway, or meet in the service station, and you'd go in convoy."

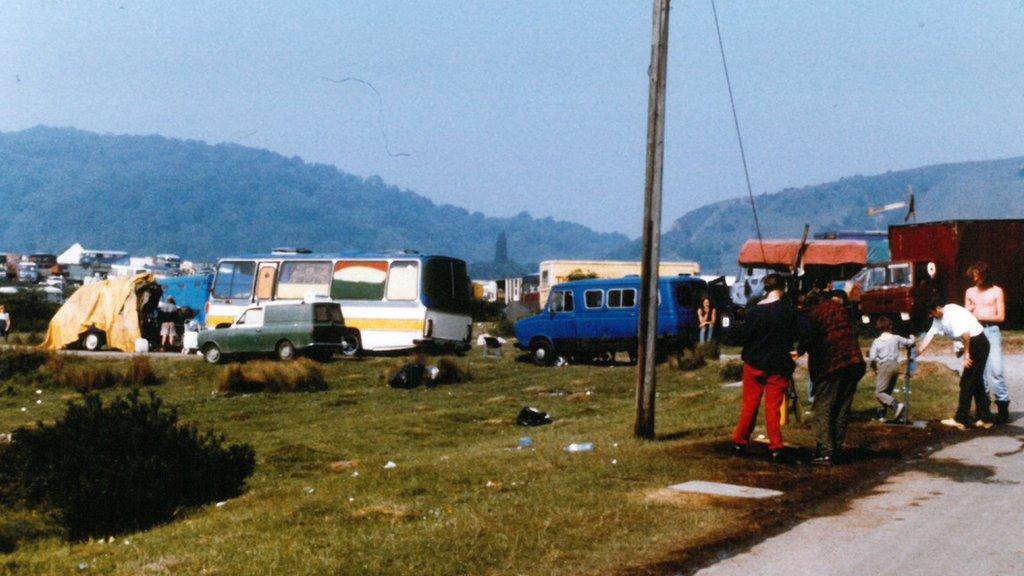

People would travel to festivals like Castlemorton in convoy

Ravers remember it as a positive atmosphere with like-minded people

Mrs Spragg believes the combination of a gloriously sunny bank holiday and the promise of a ready-made party was what drew ravers to Castlemorton.

"You were getting [sound system collectives like] Spiral Tribe and the big [underground] DJs of the time latching onto the idea to take it out doors and the free festival scene was a real "no brain" way to do that," she said.

"They could see what was happening with the travellers and [knew] they could turn up.

"[It wasn't] helped by the media to be honest - if they hadn't said anything it would have just stopped as it was.

"But as soon as you start putting it out on the television that there's this huge party everyone jumps in their car and just turns up."

The 392-acre Castlemorton Common was made a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1986

The music went on until the early hours and started again at midday

And so the underground warehouse rave scene arrived, with its big sound systems in tow.

Mrs Spragg says there was "some resentment" among the travellers who felt their event had been "taken over" and part of the festival was declared a "raver free zone".

But while the travellers felt surrounded, so did those living on the common, such as Mary Weaver.

"On the bank below the hills it was tightly compacted, and as you went down by our [farm] pond there were double-decker buses lined up all along there," she remembered.

"It was very disruptive because no-one could get in or out - not with a vehicle.

"They had some very loud sound systems and they played very loud music, but in actual fact the music didn't worry me that much, because I like music.

"But it did other people, it drove [them] mad. It stopped about five o'clock in the morning and it started up about midday."

Travellers used festivals as a way to network, find new work opportunities and meet friends

News of the festival spread locally, helped by the volume of the music, which could easily be heard in Malvern 10 miles (16km) away - a fact former resident, Tim Holloway, can attest.

"I was coming back from an all-night party in Malvern and walking back at about five in the morning I could hear this booming beat - I had no idea what it could be," he said.

"Later someone told me there was this massive rave on Castlemorton Common.

"We rode through on motorbikes and I was stunned, it was just enormous. We took it all in, soaked up the atmosphere - it was just an enormous party - a gift when you're 21."

Clare Buchanan, who was on a gap year, heard about the festival when some of those en route stopped at the supermarket in Malvern where she worked.

"They looked like full-on hippies, which is what I wanted to be," she recalled.

"My and a friend went along to investigate what was going on. We were dropped off and there were two policemen at the end of the road across the common.

"There was a very chilled atmosphere."

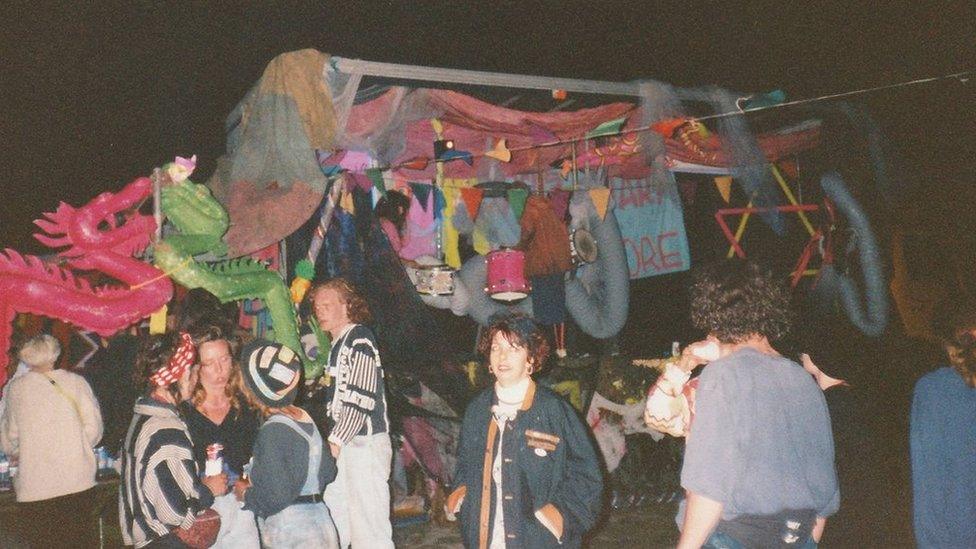

Back To The Planet played at Castlemorton Common in 1992

But by Saturday night, West Mercia Police had arrived and put up a cordon.

Officers were stationed with Ms Weaver and fellow resident Audrey Street who said she "never went out once" the whole week.

She described how the single track road across the common was completely blocked in places by the encampment and the complete absence of toilets had another unwanted effect.

"Every time I went out there were people in the field toileting - every time you looked out there were men with their trousers down," she said.

Mary Weaver's farm, pictured now, was taken over by festival-goers

The encampment stretched up the hill from the farm near her house

The ravers drifted off once the weekend was over but the travellers remained at Castlemorton until the Friday, partly to try and clear up, Mrs Spragg claims.

"I think a lot of people were depressed about the mess and the waste, that's why so many [of us] stayed behind and tried to clear up.

"Although people don't think it, the traveller ethos at free festivals was "leave no trace" - you went there, you had a party you cleaned up.

"In fact I was one of the many people who used to take wild flower seeds, and that would be the only thing I left - that sounds like I'm a real hippy but that was the vibe," she said.

But there was no chance revellers would ever again have the opportunity to "leave no trace".

As the festival wound down, police faced angry questions at a public meeting in Castlemorton village about how they had responded.

The fallout of the festival had an impact on the travelling scene

In a press conference on the Friday after the common had been cleared, then Chief Constable, David Blakey, defended his "softly softly" approach.

"Faced with... the number of people that were there, there was no way I'm going in with riot shields, with public order gear, to move them off," he said at the time.

Officers arrested about 50 people over the course of the festival - mainly for drug offences - and 10 were taken to court for public order offences. The case cost millions and saw all the defendants acquitted, though one other person did plead guilty to the same offence.

The force later admitted they had been "caught off guard" by the sudden arrival of so many people.

An exclusion zone was set up banning convoys from the area

Determined not to have history repeat itself, the following year they set up roadblocks across the area, with 300 officers being fed from a special kitchen set up in the village hall.

The Malvern Hills Conservators - the charity set up to look after the hills and commons - obtained an injunction which enforced a five-mile "exclusion zone" for convoys of vehicles around Castlemorton during the bank holiday weekend.

Others called for long-term powers to stop raves and free festivals, including Castlemorton's then-Conservative MP Sir Michael Spicer, who even raised the matter in Parliament.

Then in 1994, the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act was passed, giving police the powers to stop vehicles anywhere within five miles (8km) of a rave and turn them away.

It also included rules targeting gatherings of more than 100 people listening to music at night and even went as far as delving into genres, said Prof Robert Lee from Birmingham Law School.

"One of the most bizarre things is that they tried to define what music was, including wholly or mainly repetitive beats played time and time again," he added.

Police faced angry questions at a public meeting in Castlemorton village

Mrs Spragg, who gave up travelling in 1995, says what happened at Castlemorton had an adverse effect on the community she belonged to.

"The travelling scene did carry on but it was a very different change of lifestyle for people - they moved onto farms instead of living on free sites so much, and people were a lot more scared.

"If it had been a big event, [which] had been staged [and] had cost thousands of pounds it would have been all right.

"But because it was poor people, with no money, doing something they haven't been granted permission for, suddenly it was the crime of the century.

"It did mean the end of the travelling scene in a lot of respects."