Berrow Wood: The abusive school where boys were just a number

- Published

Generations of young boys were abused at Berrow Wood after being taken there by social services

Nine former members of staff at a school for boys with behavioural difficulties have now been convicted of physically and sexually abusing pupils over four decades. The BBC spoke to 10 survivors of the defunct Berrow Wood School about their ordeals, with questions remaining over how the abuse was able to continue for so long.

The first thing a former Berrow Wood pupil will tell you is their number.

Boys arriving at the country house deep in the Worcestershire countryside were stripped of their names almost immediately.

Instead, they would be largely known by their laundry number, etched in a single pair of socks, trousers and a shirt - the only clothing they wore.

It was the first sign that promises of a brighter education at the residential school masked a dark and forbidding future.

"Instead of learning to read and write, we learnt how to survive," recalled Andy, number 22.

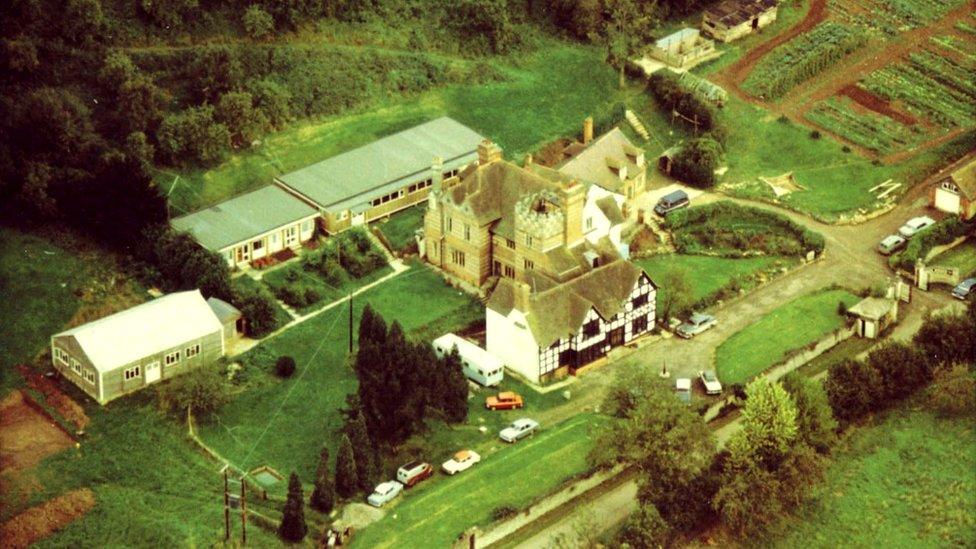

The school was set up in 1966 for "maladjusted" boys - those regarded as troublemakers who, very often, had difficult home lives.

Labelled as problem children, local authorities across England paid for them to attend Berrow Wood in the hope they might turn their lives around.

The reality could not have been further from the truth.

The abuse at Berrow Wood stretched over four decades and involved hundreds of vulnerable young boys.

"We went in with one problem and we came out with 10," said Darren Ingall, number 58.

The school as it was pictured in a brochure in the 1980s, before closing in shame in 1992

Warning - Some readers may find details in this article upsetting

First impressions were usually pretty good - timber-clad Berrow Wood was on a quiet country lane, surrounded by fields and woods.

Prospective pupils were shown the go-karts, motorbikes, a daredevil zip-wire and even a room with arcade games.

"A lot of us feel very conflicted because we have some good memories of the place," former pupil Wayne told the BBC, browsing photographs from the time.

"We had a lot of laughs. But what we had to endure was horrific."

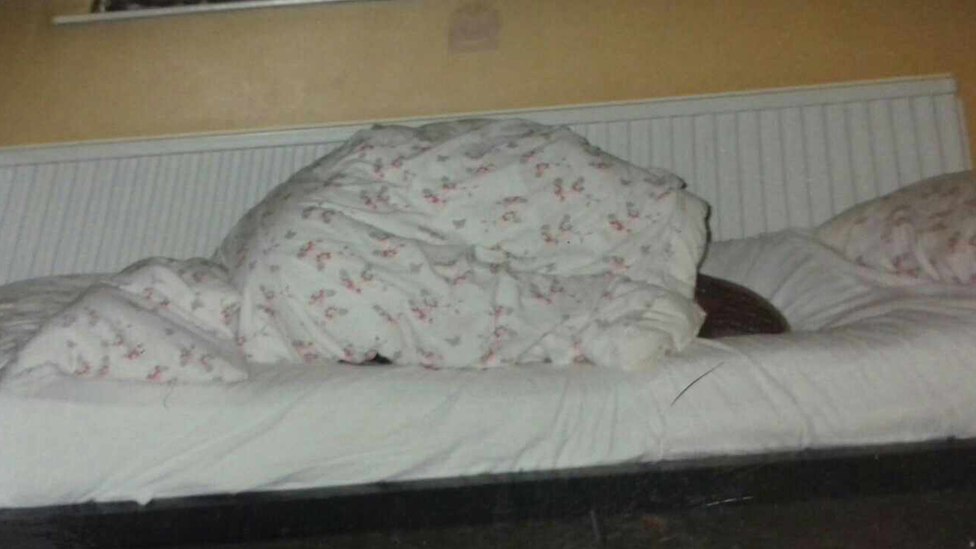

Andy*, like Wayne, was among several boys sent there by Wolverhampton Council. He slept with a kitchen knife every night after he witnessed a room-mate sexually abused by a member of staff.

"I would curl myself up into a ball and wrap myself in a duvet. There was no way I was letting them near me."

Andy's room-mate took this photo of how he slept while at Berrow Wood in the 1980s

From its inception the school was privately owned, which meant it was free from local authority intervention and hidden from scrutiny.

Men were employed as "housefathers" to look after the boys.

Among them were Keith Figes and Maurice Lambell, who groomed some of the most vulnerable pupils.

James*, number 7, has only recently spoken for the first time about the abuse he faced at the hands of the two men. He is now 66 years old.

"I was raped there every night. Fifty-six years ago and I can remember as it was today," he said.

"Every time I put my head on the pillow all I can see is that school."

Darren Ingall, pictured as a teenager with his grandmother, grew up in Guildford

Darren Ingall was sent to Berrow Wood by Surrey County Council social services aged 12. He has waived his right to anonymity to tell his story.

Like many of the boys there he took up smoking. With hardly any perks, cigarettes were an exciting treat.

At 14, housemaster Barry Hastings began routinely waking Darren in the night and taking him up to his room to smoke.

It was there the abuse began, degenerating as the nights progressed.

At 15 and unable to cope any longer, he fled, hitchhiking all the way home to Surrey.

"I even thumbed a lift on the M50," he said. "This guy was in a Jag and I told him I was on a sponsored hitch hike."

Darren went back to visit the site of the former school where he was abused

Abuse was so ingrained in the culture at Berrow Wood that it continued even as staff left and others joined.

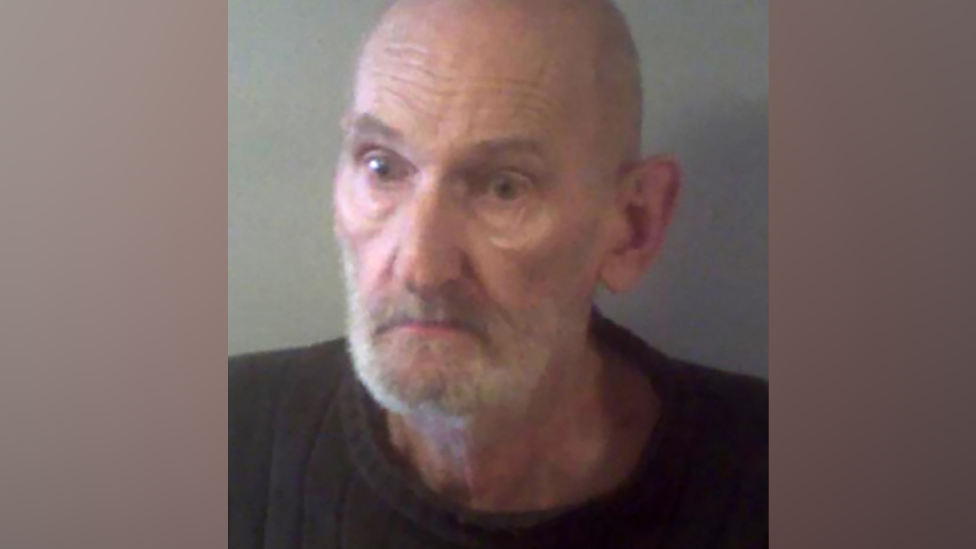

In 1984, it was bought by Alan Gorton, a smartly dressed former boxer, with bearded Ron Morris as headmaster. Together they presided over a brutal regime that many members of staff fell in line with.

Morris, short in stature but described as a "sadist", had a motto for the boys: The only rights you have here are to eat and breathe.

Corporal punishment was legal at the time, but Gorton and Morris appeared to relish savagery. The beatings meted out were horrific.

If you've been affected by any of the issues in this article, help is available via BBC Action Line

Some boys were battered with dumbbells for minor misdemeanours like giggling or not paying attention; others were hit with irons.

Morris, who is now dead, had his own technique of battering the boys who were as young as 11 - raining down blows while jumping and stamping on them, often in front of the whole class.

Wayne recalled running away in his first week only to be returned, stripped of his clothes and pinned up against a wall by Morris, strangled until he was breathless and bright red.

Others had their teeth knocked out.

"You had to be like wallpaper to avoid being targeted," said Andy.

Ron Morris, pictured here in a school brochure, was described as a "sadist"

Distraught pupils regularly fled, often running miles to the nearest police station - others hitchhiking home.

Time and again they were sent back into the clutches of Gorton and Morris, the absconding children "beaten to a pulp" once behind closed doors.

For Paul, number 35, the abuse started when he was invited into a staff member's office and told he could improve his behaviour grade.

Grade one meant privileges such as taking trips to Malvern or Tewkesbury. At the opposite end - grade five - pupils had to collect sheep manure with their bare hands, were made to stand in front of a clock all night, or dig a hole in the ground for hours.

Paul ran away and made it home to Wolverhampton. The BBC has seen a letter from Gorton to Paul's mother, demanding he be returned to school.

He has also kept a letter from the education department at the city council stating he should go back.

"The quickest thing for social services was to be seen and not heard - pass us off, 70 miles away," said Paul.

"I had nobody, I was left there for three years. I even got beaten up for being homesick."

Pupils were as young as eight at Berrow Wood School

Ian* also from Wolverhampton, recalled escaping barefooted across fields.

"I knew those fields like the back of my hand. I used to steal farmers' wellies to try and get to Malvern train station," he said.

Another punishment was to be taken to a church in Tewkesbury dressed only in pyjamas and a dressing gown.

"That church was packed," said Paul. "Why did no-one say anything?"

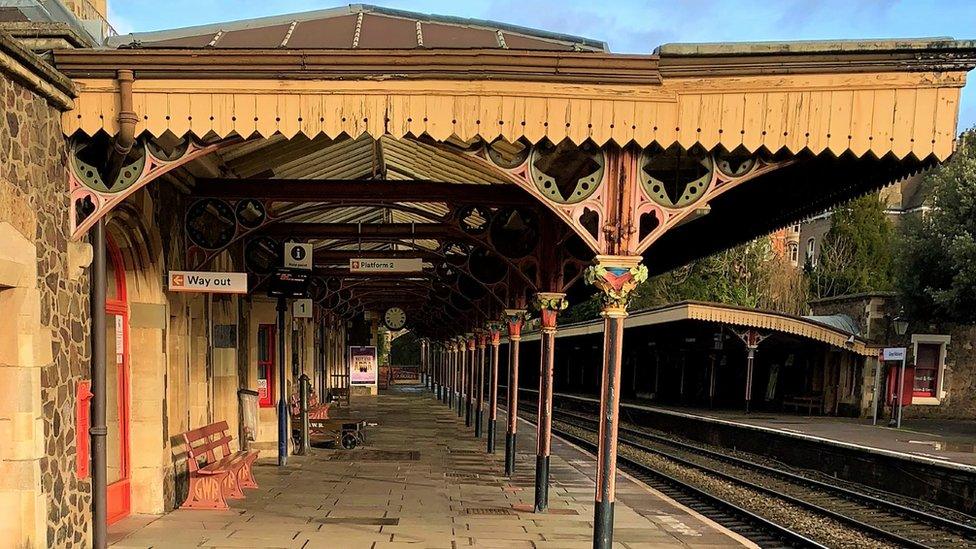

The boys regularly ran away to Great Malvern railway station - 12 miles from Berrow Wood school

One day in 1991, pupils were told abruptly it would be their last day at Berrow Wood. The school was closing, and West Mercia Police had started investigating allegations of abuse.

Paul, then 16, remembers watching his friends get collected and driven back home.

"Different social services came to pick everyone up, but Wolverhampton Social Services never came to get me." He was left to get a train by himself.

Two years later, six members of staff, including Morris and Gorton, went on trial at Wolverhampton Crown Court.

Ian was among the former pupils giving evidence.

"I was emotional, crying in the dock," he said. "Mr Gorton was staring at me and I mouthed to him 'It's your turn now'."

Gorton was found guilty of actual bodily harm (ABH) against three boys and common assault on two boys. He was jailed for 12 months.

Morris admitted ABH against one boy, common assault against two boys and cruelty to two boys, and was jailed for eight months.

Philip Gray, a housemaster, was jailed for six months after pleading guilty to ABH and cruelty.

Three others - David Laughton, Peter Larner and Peter Gorton - received community sentences after being convicted of assaulting pupils.

Barry Hastings died in jail after being convicted at Canterbury Crown Court

After finding the courage to tell police of his abuse some 40 years later, Darren watched from the public gallery as Barry Hastings was jailed in 2019.

"He was the big guy, the ex-SAS soldier and I was a little kiddy, but in court I was the adult and he was the old man with a stick."

After Keith Figes left Berrow Wood having abused countless boys, he went to Badgeworth Court School in Cheltenham in 1973 and repeated his sickening behaviour there.

When seven former Badgeworth pupils bravely told police what happened, a judge hearing the case in 2000, external - in which Figes admitted 12 charges of indecent assault - gave him a suspended sentence because he was a "reformed character", sparking anger and disbelief.

He was jailed on Tuesday, after West Mercia Police's painstaking investigation into his crimes more than half a century ago.

Judge Martin Jackson issued a warrant for Maurice Lambell's arrest after he failed to turn up to court for his sentencing.

Their cases involved seven victims, two of whom died after making their statements.

The Crown Prosecution Service still allowed their evidence to be heard in court, their stories pointing to clear patterns of abuse.

West Mercia Police believe there were many more abusers employed at the school, but they died without ever facing justice.

Keith Figes and Maurice Lambell bring the total of Berrow Wood staff convicted to nine

Shortly after closing, the school building at Fishers Place in Pendock was turned into private homes.

Residents said former Berrow Wood pupils occasionally turn up, desperate for answers.

Why were they sent there? How could no one see the signs?

Both Darren and Paul's parents wrote to their local authorities highlighting how desperately unhappy their sons were, but nothing was ever done.

Many men are still coming to terms with what happened to them. Some, like Ian and Wayne, have spent years in and out of prison. Others have worked tirelessly despite having no qualifications and unable to read or write.

"Because of Berrow Wood I led the life I did," Ian told the BBC.

Darren retraced the steps he took as he fled Berrow Wood, aged 15

City of Wolverhampton Council said it was looking into the issues raised by the BBC.

Tim Oliver, leader of Surrey County Council, said: "We have the deepest sympathies and care for anyone who has been harmed as a result of institutional abuse.

"While we would not comment publicly on any individual case whether current or historical, we will always investigate any allegation of abuse whilst in Surrey's care.

"If anybody believes a crime has been committed we would encourage them to report it to the police."

'It's not your fault'

Darren, now 53, said therapy had helped him come to terms with the trauma of Berrow Wood.

"I don't feel like a victim any more. I feel like I'm on top of the world - my kids are happy, my mortgage is paid off and I don't give a monkeys about what he did."

He said he had waived his right to anonymity so he could give a message to anyone else who had been abused.

"I know what its like to be frightened of an adult who is in authority over you and how hard it is to speak up," he said.

"You're the little guy and maybe you'll think nobody will believe you.

"But if being a child is about learning to be an adult, it can't be that child's fault can it - if they've have been led into making mistakes by an adult authority figure.

"I cannot say it enough: it really isn't your fault."

*Some names have been changed

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published3 October 2023