Plant expert Patricia Wiltshire helping police catch killers

- Published

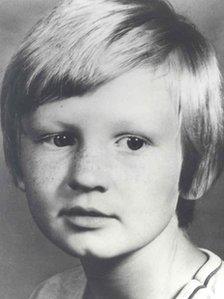

Christopher Laverack's body was wrapped in plastic and weighed down

After an investigation spanning three decades, Humberside Police revealed this week that its longest-running unsolved murder case had been solved by forensic evidence from plants.

Nine-year-old Christopher Laverack was brutally murdered and his body dumped in a beck after he had been left alone to babysit at a house in Hull in March 1984.

His uncle, Melvyn Read, had long been a suspect, but it was not until a forensic palynologist was brought in to review the case in 2007 the evidence against him became conclusive.

Dr Patricia Wiltshire, who specialises in identifying pollen and spores, was already well known to the force, having helped them find the body of Joanne Nelson, a Job Centre worker from Hull who was murdered by her fiance Paul Dyson.

The disappearance of Miss Nelson in 2005 sparked the biggest search operation ever carried out by Humberside Police involving hundreds of officers, volunteers and even the army.

'Satisfying' job

Pollen found by Dr Wiltshire on items belonging to Dyson directed police to an area of woodland near Malton, North Yorkshire, where Miss Nelson's concealed body was found.

While looking at the Christopher Laverack case, Dr Wiltshire concluded there was enough unusual pollen and other plant matter on the clothing he had been wearing the night he was killed ultimately linked him with his uncle's garden.

An ornamental brick used to weigh down Christopher's body was also forensically linked to a water feature at Read's property.

Dr Wiltshire, who lives in Surrey, said the link between pollen spores on Christopher's clothing and Read's garden stood out to her "like a beacon".

She said: "It's quite satisfying seeing a job finished. This job was on the police books for such a long time.

Dr Wiltshire said she was relieved the case had been solved

"I am just relieved for the police and for the parents, they must have been feeling dreadful. The fact that someone has been found to be guilty, it puts the case to bed."

In 2003, Read was jailed for seven-and-a-half years for sex offences involving children.

He was arrested in 2006 in connection with his nephew's death but detectives were unable to gather conclusive evidence to charge him with the murder before he died from cancer in Hull prison in 2008.

Humberside Police said the case had "frustrated" detectives, who had applied forensic investigative techniques to the case to no avail.

A spokesman said: "Read was a clear suspect, having now been identified as a predatory paedophile, and although the case was tantalisingly-close to being solved, there lacked the final piece of a very complex jigsaw."

Det Supt Ray Higgins, who asked Dr Wiltshire to review the case, said: "This case has taken many years to resolve.

"We would all wish the evidence to convict were available sooner and whilst Read was still alive to face trial, however that was not to be."

Soham case

Born in south Wales, Dr Wiltshire first became interested in botany as a child, when her grandmother would teach her the Latin names of plants on walks.

After gaining a degree in botany and ecology at King's College London, Dr Wiltshire lectured there and at University College London before receiving a phone call that took her career in a new direction.

Hertfordshire police asked her to help them with a murder case and when presented with her findings the suspects confessed to the crime.

"The results were really quite outstanding. And word got round, of course."

She says she has since worked with every police force in England, Wales and Ireland and four in Scotland.

She was involved in the Milly Dowler, Sarah Payne and the Ipswich prostitutes murder cases.

Most notably, she helped secure the conviction of Ian Huntley for the Soham murders of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman and gave evidence at his trial.

"The palynology evidence certainly helped to show that Huntley had been at the scene where the girls were placed," she said.

"Without any doubt in my mind, and the jury's minds eventually."

Working on such cases could be "depressing", she admitted.

"You just have to detach and look at it as a scientific exercise. You have to go into it in an unbiased way and form your conclusions after you have studied all the evidence.

"The analysis is sheer drudgery, working out all the data. The best bit is when you can see something and you think 'gosh, I have got a conclusion that might help'."

- Published1 August 2012