City of Hull on crest of a cultural wave

- Published

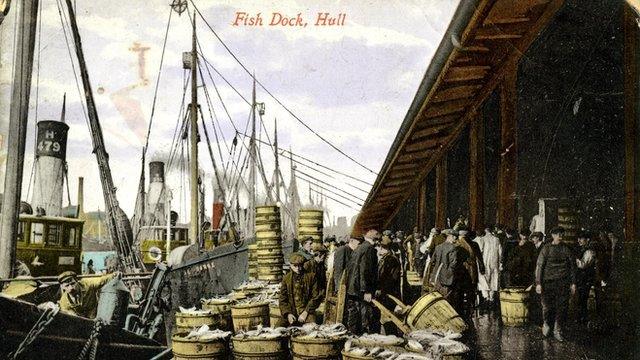

There could be a certain, distinctive smell as the wind blew into the city centre across the fish dock.

For decades Hull has been a rather unfashionable place - but now it finds itself basking in the glory of being named City of Culture for 2017.

It is a place with a royal name, Kingston upon Hull, where King Charles I was turned from its gates at the start of the English Civil War by the Parliament-supporting populace.

It even kept its own cream telephone boxes and an independent communications company, refusing to follow the trend of changing to the red box, operated by BT.

It is a proud Yorkshire city that for centuries has turned its back on the rest of the county to look seawards.

Wrinkled noses

That penchant for putting to sea led to the development of a large fishing fleet based at the port, the mark of which was a distinctive smell blowing across the city centre.

However, despite wrinkling a few noses nobody was really put out at the fishy smell because, as the local saying had it, "What you can smell is money".

With its place on the Humber Estuary in the east of Yorkshire the city has had strong links with the Baltic states and the Icelandic fishing grounds.

The first dock arrived in Hull in 1778 and by 1800 almost half of the country's fleets of whalers sailed out of the port.

As the whaling declined so the fishing took over.

Three-day millionaires

The Silver Pits, a fish-rich part of the North Sea, led to fishermen from across the country migrating to Hull and as trawling developed it was at the forefront of a deep-sea fishing boom.

During the 1950s, 1960s and into the 1970s, the vibrancy of the fishing trade had a strong spin-off for the town's economy.

The trawlermen would be away from port for weeks at a time and back home for only a few days.

The three-day millionaires, as the men were called, became a common sight in the city as they worked their way through the profits of a bountiful trip in a matter of days.

The men would hire a taxi to transport themselves around the city's numerous watering holes wearing distinctive, flashy suits.

But, then the Cod Wars intervened, depriving the east coast ports of large swathes of their rich fishing grounds.

Confrontation at sea

Iceland started extending its territorial limit to exclude foreign vessels from the waters it claimed as its own.

This led to confrontations at sea between the Icelandic coastguard and trawlers from Hull and Grimsby.

The reliance on fishing proved to be a problem as the trawler fleet shrank during, and after, the two decades of the Cod Wars.

It was the beginning of a slow decline for the city and its people.

However, Hull had faced even worse times and survived.

During World War Two, it became the second most bombed city in England after London, with 90% of its buildings damaged.

Bombing raids killed and seriously injured thousands of inhabitants, with hardly a house undamaged in the city.

Easy target

Enemy bombs are not the only thing to have rained down on the city.

About 1,200 people were killed by bombing in Hull

It has long found itself an easy target for the surveys and studies claiming an unwanted title for the place.

Just this month, a newly-commissioned study said Hull is the worst place to live in England (eight places in Scotland were apparently ranked worse).

It is just the latest in a long line of dubious accolades.

Of more credence are figures showing a lower level of educational attainment, lower wages and higher unemployment than average.

And yet the city survives and with the latest news it may even thrive.

- Published20 November 2013

- Published20 November 2013

- Published14 November 2013

- Published12 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

- Published30 October 2013

- Published8 October 2013

- Published15 November 2012

- Published15 November 2012

- Published1 March 2012