Beverley Minster: The history of a sanctuary town

- Published

The minster was a safe space for fugitives fleeing persecution across England

The ancient right of sanctuary saved countless lives, providing welcome protection from prosecution and persecution for those accused of crimes. A new exhibition in Beverley, East Yorkshire, charts the town's "exceptional" history as a beacon of hope for fugitives and the lives of some of those who sought refuge in the town.

The year was 1479 and Elizabeth Beaumont of Hetton in West Yorkshire had just killed her neighbour Thomas Aldirlay.

Knowing the punishment for murder would be her execution by being burnt at the stake, she made the 75-mile journey over two days to the minster in Beverley, East Yorkshire, for safety.

Elizabeth's fate is unknown, but it is thought she may have been banished from England.

She is one of 439 people who, between 1428 and 1539, sought sanctuary in the town and whose name has been recorded in a document set to go on display.

What was sanctuary?

Beverley Minster was known as being a place where those needing a safe haven from alleged crimes could seek refuge and be protected.

It was granted the special privilege in 938 by King Athelstan, who is said to have visited the tomb of John, Bishop of York while heading to fight the Scots.

The bishop, later recognised as a saint, was known for healing the sick and created a monastery on the site where Beverley Minster now stands.

Athelstan reportedly credited his victory to the saint and granted the right of sanctuary within a two-mile radius around John's tomb.

King Athelstan said his victory against the Scots was down to John, Bishop of York

Fugitives who reached the area around the minster were able to claim sanctuary and immunity from prosecution.

At the time, people accused of wrongdoing feared for their lives, with victims being inclined to take matters into their own hands and seek revenge.

The sanctuary was established to shelter people for up to 30 days before they were handed over for trial or they decided to flee once more.

Stones still stand in nearby villages marking the start of the sanctuary area, where pursuers were fined for trying to catch fugitives inside the boundary.

Stones such as one seen here in Walkington were placed two miles away from the minster to mark the sanctuary area

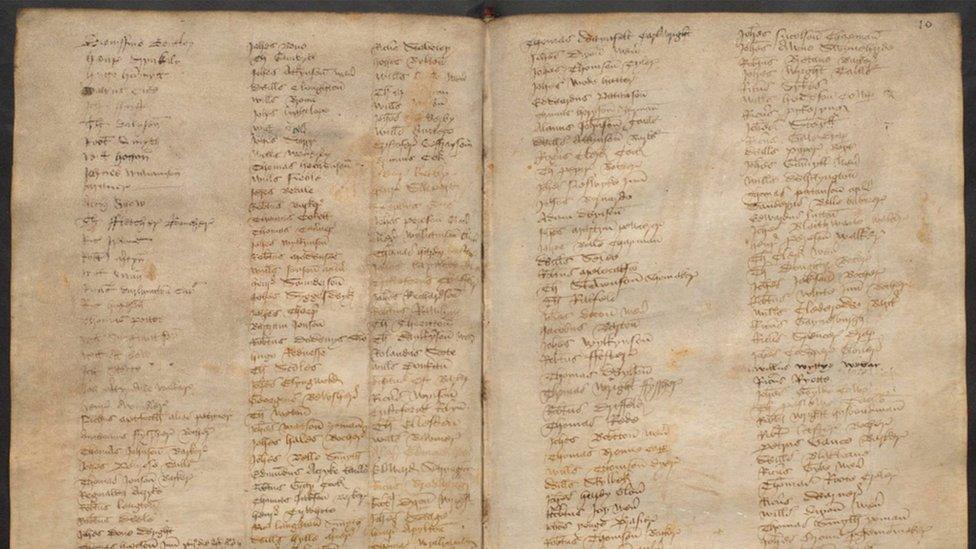

A book set to go on display contains hundreds of names of sanctuary men or grithmen, detailing the journeys of people hoping for shelter.

York butcher Culyng is one of those recorded sanctuary-seekers. He inherited debt from his father and fled to Beverley after creditors came to claim money he could not afford to give.

One of the most high-profile sanctuary seekers, although not included in the records, was Sir John Holland, half-brother of King Richard II.

In 1385, just outside York, he killed the Earl of Stafford's son in vengeance for the death of his own squires.

At the time Sir John was accompanying the king on his way to Scotland, but fled to Beverley knowing his fate would likely be death.

The king ordered the seizure of Sir John's land as punishment, but a year later would reconcile with the Stafford family.

When fugitives arrived in Beverley, details were taken about who they were and why they were seeking sanctuary.

Hundreds of names of people who sought sanctuary at the minster are documented in a small notebook

At the minster, fugitives would swear an oath and do small jobs in return for their safety.

If they were still wanted after their 30 days they had several choices.

One was to go on trial and accept any punishment meted out. Many who chose this route were executed.

Another option was to leave the minster and risk living as an outlaw under constant threat of being killed.

Some were banished from England, while others lived their lives in the two-mile sanctuary area and attempted to start news lives.

The privilege ended in Beverley in 1540, with Henry VIII abolishing all rights of sanctuary by 1624.

A new project detailing the lives of the grithmen and those who tried to protect them has been created alongside the University of York.

Videos about those who fled prosecution and a digital version of the notebook are on display, along with stories of modern-day refugees.

Dr Louise Hampson, from The Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture at the University of York, said the exhibition looks at our past and shared present.

"Telling Beverley's exceptional sanctuary story and bringing it alive for people today has been a real challenge which we have very much enjoyed," she said.

"The medieval story is fascinating, but can seem remote so we have looked for contemporary connections and relevance to modern life.

"We were also keen to explore the wider issues around modern sanctuary, and we were very privileged to be able to talk to some Syrian refugees who generously shared their experiences, their hopes and their resettled lives in East Yorkshire."

Follow BBC East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.