Bingo: 'Generational' game gets reinvented for new crowd

- Published

Becki Tate, pictured far left, and friends use tablet devices to play bingo at Mecca Bingo in Hull

Bingo halls, like many other traditional entertainment venues, have faced some tough years. The indoor smoking ban in 2007 has been just one of several recent challenges they have faced, with Covid and the cost of living crisis serving as the final nail in the coffin for others.

But green shoots are perhaps emerging, as operators find new ways to bring in customers. BBC News went to one bingo hall in Hull to find out how the industry is attempting to stay close to its roots, while protecting its future in the face of outside pressures.

As I arrive in the foyer of Mecca Bingo on Clough Road in Hull, Jackie Marshall, the stalwart assistant manager, is greeting customers - many of whom, she tells me, have become friends.

It is about 20 minutes before the first game of the evening and Ms Marshall has just clocked a familiar face: 82-year-old Janet Gibson is perched on a stool, feeding change into a slot machine.

The octogenarian has been a regular for "more than 20 years", Ms Marshall tells me. For now, I leave her to her game.

Jackie Marshall has worked for Mecca Bingo since 1986

Ms Marshall has worked at this hall since the 1990s and few are better qualified than her to give a view of the challenges facing the industry.

"The smoking ban was a bit of a shock," she admits, referring to the 2007 legislation that began the rot for many halls and other traditional venues.

"We did lose some business. It took a while to bring them back.

"Then we had Covid."

Figures provided to the BBC by The Bingo Association - the trade association for all licensed bingo operators in Britain - certainly show a downturn in fortunes for the country's halls.

In pre-Covid days, there were about 330 bingo halls across Britain, compared with 262 today.

We do not need to look far to see an example of this: just a few miles down the road from the Mecca in Hull, the Cecil closed in February.

Customers are, however, beginning to return to venues, the Bingo Association says.

The main hall at Mecca Bingo in Clough Road, Hull

Bingo halls are clearly having to adapt to stay afloat. They are having to offer more than a game of bingo - and the gaming companies have an eye on the future.

Outside, on the side of the Mecca, an LED ticker screen invites people to "come and join us for a great experience".

Ms Marshall says: "Bingo has definitely evolved. We are seeing a lot more younger customers coming in, even if they only come in from 6pm to 9pm and then go off into town."

As we chat in the lounge area, a group of women in their 30s are sitting around a table, laughing and drinking. They are logging into electronic bingo units.

"Bingo is generational," Ms Marshall explains. "For many people, the first place they come when they turn 18 is here."

Bingo halls are also "close-knit communities", she adds.

"I have made lifelong friends here. People look after each other. It is a safe environment. If one of your regulars misses a couple of nights, you will often put the feelers out, just to check they are OK."

While still a form of gambling, many people see a bingo card as a gentler way of having a flutter, although some halls have attracted criticism for hosting higher-stakes slot machines.

Couples Andrew and Carol Mortimer and Andrew and Marie Marsters enjoy a drink and game of bingo in Hull

Scanning the lounge, I notice a distinct lack of dabbers. Whatever happened to the dabber?

"Younger customers still get excited by the dabbers," says Ms Marshall. "You can still play with a dabber and paper if you want to, or you can use an [electronic] unit."

Here in the lounge, play is relaxed, with chatter encouraged. But behind a sound-proofed wall of glass, in the sprawling hall, it is serious business, with silence only broken by losers' exasperated exhalations contrasting starkly with winners' cheers.

Occasionally, Ms Marshall "calls", although she tells me "there are far better, professional callers".

"You need a very clear voice," she says. "Good timing and good rapport with the customers is also important."

The history of Bingo

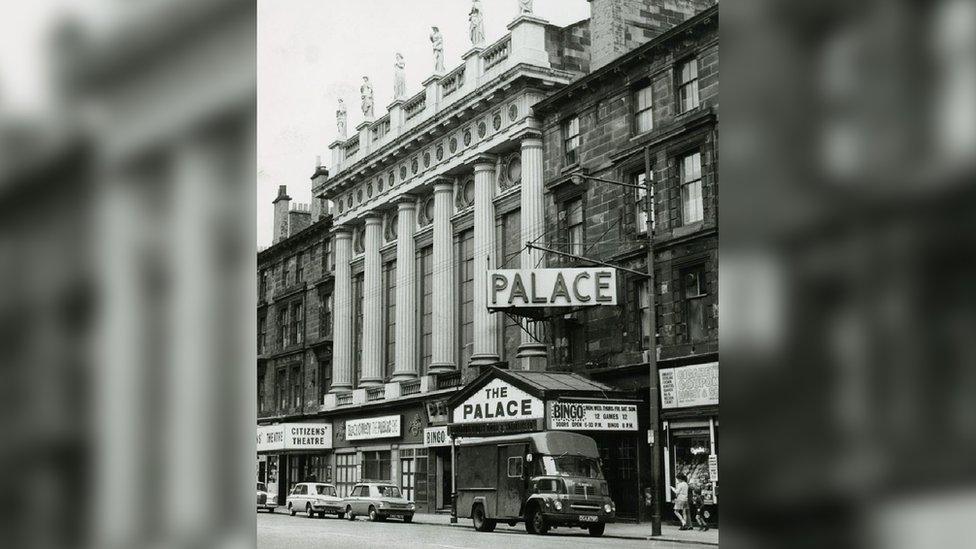

Palace Bingo Hall in Glasgow, pictured in August 1968

Bingo historian Carolyn Downs, from Lancaster University, says the game has been traced back to the late 16th Century in Italy.

"Americans say they invented the name bingo in the 1930s," says Ms Downs. "But certainly in 1926 I found records of it being played in Britain."

After World War One, bingo was popular in ex-servicemen's clubs and working men's clubs, she says, and by the 1950s, its popularity was soaring.

Ms Downs says: "Butlins were running massive games, even putting up marquees for them.

"Under the rules back then, proceeds had to go to charity. In 1958, Butlins gave £50,000 to the National Playing Fields Association."

On 2 January 1961, new legislation allowed bingo to be played in clubs.

"The government assumed it would allow bridge and casino-type games," says Ms Downs. "They did not envisage bingo clubs being set up, but that's exactly what happened."

Mecca Bingo Hall, Eglinton Street, Glasgow, pictured on 24 May 1981

By the mid-1960s, there were six million members of bingo clubs and the 1968 Gaming Act was, according to Ms Downs, "an attempt to put the genie back in the bottle".

"Bingo clubs continued but were kept under very tight restrictions. A lot of the smaller, independent clubs were bought by the likes of Gala."

"We started to see a decline from the 1980s and by the 1990s there was real decline. The smoking ban really hampered bingo halls, as did online bingo although that is very different to terrestrial bingo," she says.

"More recently, we have seen a bit of an upswing in the popularity of bingo. It is pretty popular with students seeking an affordable night out.

"Bingo halls have had to find new and interesting ways to bring in customers, such as drag queen bingo, to make it a more fun night out."

Sitting with friends, Becki Tate, 35, tells me she thinks "bingo is moving with the times".

She adds: "I started coming here with my stepmum. There are definitely more younger people going to bingo."

Her friend Sarah Cone, 34, adds: "When you go to bars, it can be really hard to talk to your friends.

"Here, you can come along, have a drink and a chat and enjoy a game."

While bingo may attract younger participants like Ms Tate, Myles Baron, chief executive of The Bingo Association, admits recent times have been turbulent for the industry.

By May 2021, attendances had dropped "between 30 and 40%" on pre-pandemic levels, he says.

Meanwhile, about 46 halls had "failed to make it through", he adds.

The derelict Astoria cinema in Brighton, later used as a bingo hall

However, according to Mr Baron there are signs of recovery: "Currently, we're 10-15% down on pre-Covid levels, so the gap is closing."

Undoubtedly, the cost of living crisis is hampering the recovery, with Mr Baron putting down the closure of 26 halls to rising costs.

"Bingo halls are big old buildings with up to 1,400 seats that require a lot heating and lighting," he says.

But, some halls appear to be bucking the trend.

Mel Kassim is general manager of a site in Wakefield, where he says attendance is up compared with before the pandemic.

The focus is on improving the customer experience, says Mr Kassim.

He adds that recent catering improvements mean "now the food would challenge any pub chain".

Janet Gibson, pictured left, prefers to use a tablet while others still prefer to dab

At the Mecca in Hull, silence soon falls in the hall as the game begins.

"Four and six - 46," says the caller. "Eight and five - 85..."

Gone are the days of "legs 11" and "knock at the door", it seems.

Ms Marshall says: "We do use the traditional calls during Bonkers Bingo and the Stay To Play games.

"But we don't use them in main games. We say, 'let's do it properly and professionally'."

Finally, I manage to catch a quick conversation with Ms Gibson before she takes her seat in the hall.

"I come here on my own, but I usually meet a friend here," she tells me.

"I'll sometimes have a quick go on the bandits during the bingo intervals.

"If it wasn't for bingo, I'd be sat at home," she says.

If you are affected by issues raised in this article, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

Follow BBC East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published4 June 2021

- Published17 May 2021

- Published2 April 2023