Chatham Dockyard: Lasting impact three decades on

- Published

Terry Lewis (top left), Eileen Griffin (centre) and Alex Routen (bottom) have fond memories of the dockyard

The closure of Chatham Dockyard on 31 March 1984 brought to an end more than 400 years of shipbuilding and naval tradition, but three decades on what is the legacy that was left behind?

Alex Routen was 15 when he started work at the dockyard in 1958. He remembers how the work was "hard, dirty and sometimes dangerous", but he loved every moment.

"I remember walking into the boiler shop to start my apprenticeship and thinking that I'd gone back 200 years to Dickens' days.

"There were machines turning and shafts whipping round, people hammering lumps of metal, [and] pot fires with smoke all inside the building," he said.

Radio Kent reported on the ceremony to mark the closure of Chatham Dockyard

More than 7,000 skilled workers lost their jobs when the gates to the Kent dockyard finally closed, and with them went Chatham's long history of building, repairing and supplying ships for the Royal Navy.

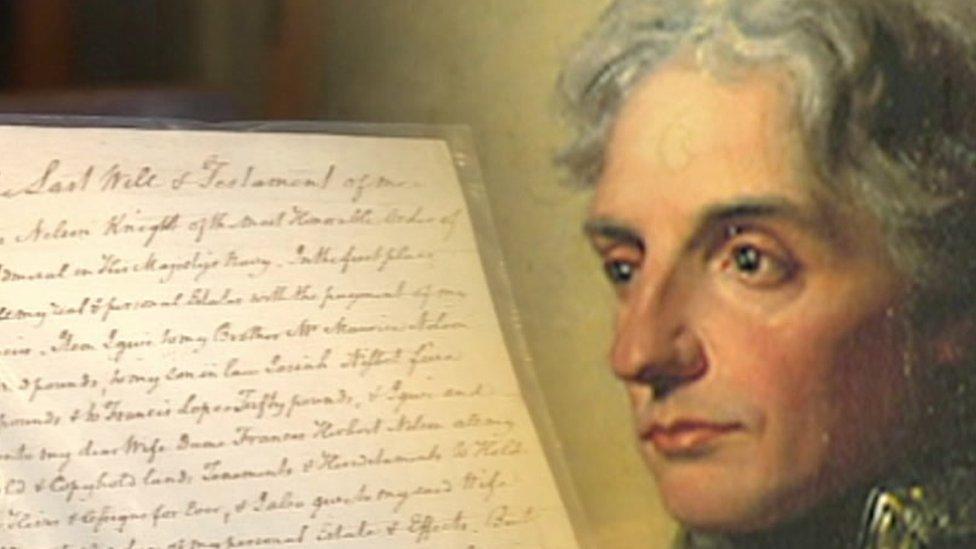

Among them was Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson's HMS Victory, on which he won the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 and was fatally wounded.

"It was like a town, a hive of industry... it was a real bustling place," said ex-worker Ian Russell, now 57.

'Clocking in'

"There would have been a lot of people in green overalls, and a few in white overalls, wandering around doing things. The cranes would have been moving to-and-fro... and there was a chipping hammer for taking paint off the boats.

"This place was a training spot for industries all around. People learnt all sorts of things in here that they can't do now."

Lots of workers arrived at the main gate to Chatham Dockyard by bike in the late 1930s

At its height, the dockyard - situated on the River Medway - employed more than 10,000 workers from more than 26 different trades, and was renowned for its high class of work.

"You used to approach the dockyard down Dock Road towards Pembroke Gate, and there would probably be 10 or so buses at the bottom," said Mr Russell.

"It was a very busy place. Lots of people on bikes, motorbikes, [and] noise... before the dockyard hooter went off and you were late."

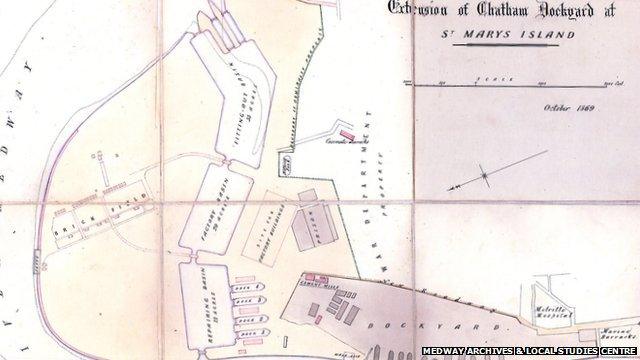

By the late 19th Century, the dockyard had been expanded to include St Mary's Island and covered 400 acres

Chatham has a rich naval history.

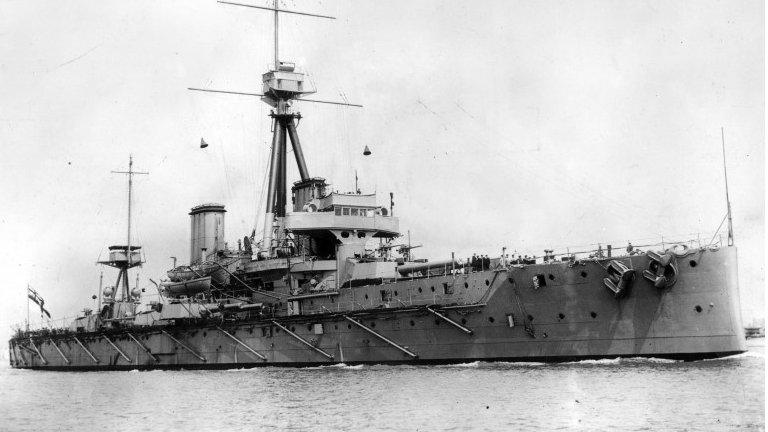

The Royal Navy first started to use the River Medway in 1547, with the first warship, the Sunne launched from a small dockyard at Chatham in 1586.

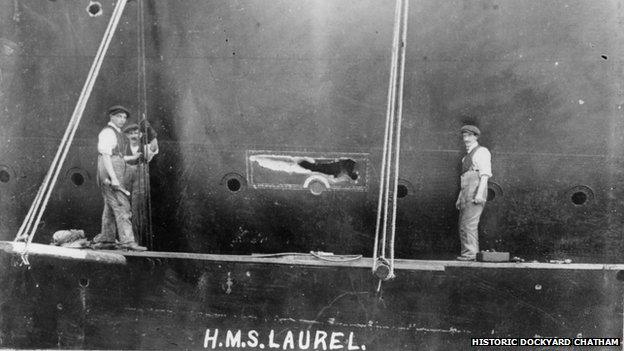

It was followed by over 400 more, as shipbuilding evolved from wooden sail through iron and steam to the 20th Century technology of destroyers and nuclear submarines.

The dockyard played a crucial role in the defence of Britain and ships from Chatham fought in every war from the battles against the Spanish Armada to the Falklands.

By the late 19th Century, the dockyard had been expanded to include St Mary's Island and covered 400 acres.

It was so huge that workers would take a bus to get from one end to the other.

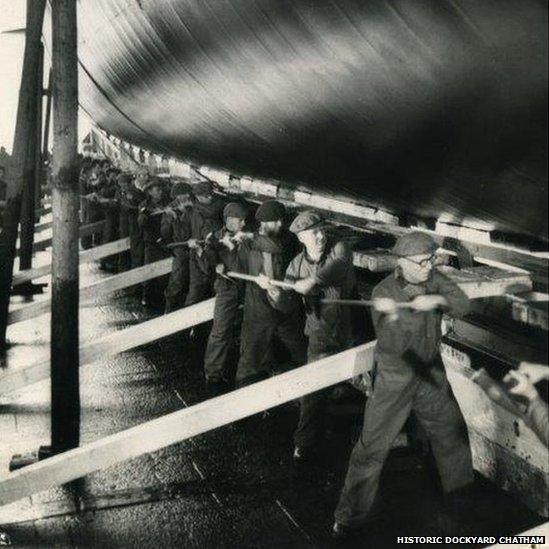

At its height, the dockyard employed more than 10,000 workers from over 26 different trades

Terrence Burnell, 76, was an electrical fitter apprentice for five years from the age of 15.

"We used to get £2 1s 4d a week, and if we were late clocking in we used to lose a quarter of an hour's pay, so we were always early," he said.

"We spent the first year making our own tools, and then every four months after that we moved to a different section... you weren't professional in all of them, but you had an insight into what it was all about.

"The training was respected elsewhere."

But it was not all work, and there was a certain amount of horseplay in what was a close-knit community both inside and outside the dockyard.

"We used to untie the boats and they used to drift off out to the middle of the basin... and the guys couldn't get back for lunch," Mr Burnell recalled.

'Your heart sank'

Eileen Griffin, who started work in the typing pool at the age of 17, said the draughtsmen used to sleep during their lunch breaks with their feet up on the table.

"I used to sneak in quietly and undo their shoe laces and tie the right foot shoe lace to the left foot shoe lace."

She remembered that "they were in such a deep sleep they used to wake up and get the shock of their lives".

Brian Jenkins was the last in a family line of workers going back 200 years to be employed at the dockyard, and remembers clearly the day its closure was announced to Parliament by Defence Secretary John Nott on 25 June 1981.

He was working as a recorder on the nuclear submarines when he heard it on the radio, and it signalled an end to his 31 years of service.

"My father had told me of several threats to close the dockyard. I didn't think they would," Mr Jenkins recalled.

By that time Eileen Griffin had been promoted to Whitehall and was working in a naval systems department where news of the impending closure was initially classified information.

"I was looking at this document saying Chatham Dockyard would possibly close... so I was getting all the phone calls from all my ex-colleagues saying what is happening, can you tell us anything - I couldn't tell them anything."

She remembers how sad it was.

"I knew all the people that lived and worked there, the atmosphere, the attitude.

"You can't put it into words - your heart sank."

Ms Griffin added that on the day the dockyard closed she just sat in her office thinking "everything's gone".

Terry Lewis worked at the dockyard for 20 years, and his father Jim was the chief union negotiator who fought hard to keep the dockyard open.

"He wanted it to survive and for all those people to keep their jobs," his son said.

"He was 64 on the day that it closed.

"On that day he honestly did think that somebody was going to push that gate shut and then someone else was going to open it up and say 'hold on a minute, this is a huge mistake'," Mr Lewis said.

The dockyard is now a thriving community with new homes, the historic dockyard and a port

Chatham and the rest of the Medway towns had been completely dependent on work from the dockyard despite the fact that the government considered that it was surplus to requirements in light of the Cold War and a Soviet military build-up.

The dockyard was wound down over three years, though experienced a brief respite during the Falklands War in 1982.

The last nuclear submarine to be refitted, HMS Churchill, and the last frigate, HMS Hermione, left the dockyard in 1983.

The BBC's Michael Buerk reported on the government announcement that the dockyard was to be closed

Speaking to the BBC this month, Sir John Nott - who was knighted in 1983 - said announcing the closure had been a very hard decision.

"Chatham Dockyard was very vulnerable in military terms to an air strike, to the mining of the access to the dockyard, the tides and a threat from submarine presence in the North Sea.

"In fact the dockyard was never positioned right for modern warfare," he said.

Sir John added: "We were also building hugely expensive facilities on the Clyde for Trident... and we had to look where we were going to save."

More than 7,000 skilled workers lost their jobs when the gates to the Kent dockyard finally closed

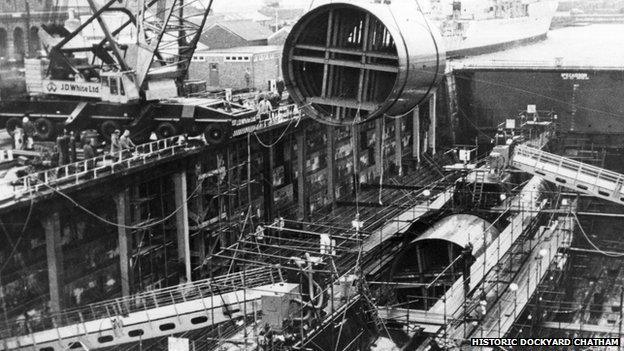

Hundreds of apprentices started their working lives at the dockyard, learning a variety of skilled trades

Shipbuilding evolved from wooden sail through iron and steam to destroyers and nuclear submarines

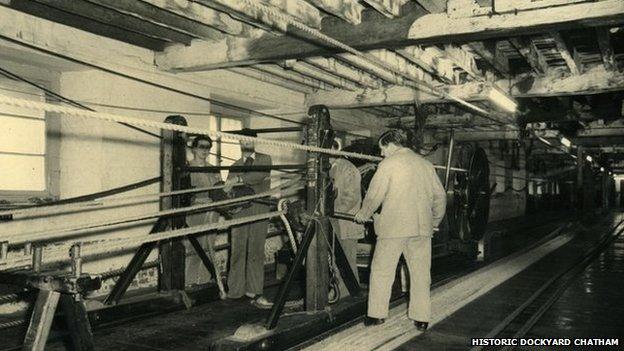

The ropery - where naval rope has been made commercially since 1618 - is still in existence today

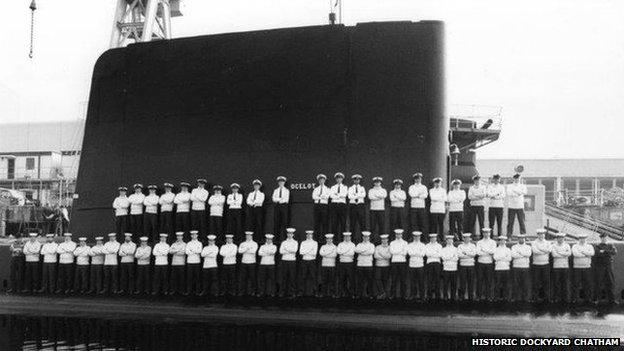

HM Submarine Ocelot was the last warship built for the Royal Navy at Chatham Dockyard

There had been 7,300 workers employed in the dockyard - 2,300 were compulsory redundancies, 2,000 workers were transferred to other naval dockyards, 1,500 retired and 1,500 took voluntary redundancy.

About 25% of the labour force were women, employed as skilled workers and in a variety of other jobs ranging from secretaries and seamstresses to cleaners and canteen staff.

There were another 10,000 people in supporting industries, with more than £4m a year spent locally from wages.

'Politically correct'

In a report commissioned by BBC Radio Kent to coincide with the anniversary of the dockyard closure, Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent, Richard Scase, said after the closure of the dockyard, and with the loss of jobs from other local employers, about 24% of the workforce in the Medway towns was unemployed.

His report concluded, however, that it had been good for the area and had eliminated unhealthy, unsafe and inefficient jobs, and destroyed bigotry and sexism within the industry.

"Some of the people I spoke to who worked in the dockyard gave me countless examples of unproductive activities, over-manning, people slacking.

"The unions controlled it as a closed shop in terms of who got jobs and the pace at which work was undertaken," he said.

But he argued that the closure was good for the area - economically, socially and culturally - and "forced" the government to invest in, and to encourage, regeneration.

Hundreds of dockyard workers marched through Chatham in protest at the closure

Former worker Ian Russell disagreed, saying: "I don't think it was anymore bigoted than anywhere else in the 70s.

"It wasn't very politically correct in those days, but that just meant that we left there very confident and rounded people that could cope with anybody."

So what has happened in the last three decades and how has the area recovered?

The old naval base was split into three parts - the historic docks tourist attraction, the working port and a residential development on St Mary's Island.

It is also home to the Universities at Medway campus, shared with the universities of Greenwich, Kent and Canterbury Christ Church and Mid-Kent College, the Dickens' World tourist attraction, and a shopping outlet.

The Historic Dockyard Chatham, external contains more than 90 buildings and structures, of which 47 are listed, plus three historical warships in dry docks - HMS Cavalier (1944), HM Submarine Ocelot (1962), and HMS Gannet (1878).

It is now one of the most complete dockyards of the Age of Sail to survive in the world.

About a quarter of the labour force were women, some of whom worked in the Chatham loft making flags

Still in existence is the ropery - a quarter of a mile-long building where naval rope has been made commercially since 1618.

The dockyard's authentic cobbled streets, industrial buildings and Georgian and Victorian architecture have regularly been used as backdrops for film and television productions.

Prof Scase said unemployment in the area was now down to "a remarkable 2.7%".

"I can't think of another community in the country where the reduction in unemployment has been so rapid over a 30-year period of time," he said.

For the thousands of workers there is no doubt that the closure of the dockyard after so many centuries was a shock and a terrible loss.

"Closing it down was tantamount to criminal," said former apprentice Rob Wilkinson.

But, as Brian Jenkins says: "You can't stop and dwell on the past, you've got to think about the future."

- Published31 March 2014

- Published31 March 2014

- Published12 December 2013

- Published29 November 2013

- Published6 November 2013

- Published21 September 2013

- Published6 July 2013

- Published17 August 2012

- Published13 May 2012

- Published6 March 2012