Great Storm 1987: The day 18 people were killed

- Published

Winds battered the south of England in what was the worst storm to hit the country since 1703

Ask people about the Great Storm which ravaged the south of England in 1987 and most will remember "that" forecast by weatherman Michael Fish, or Sevenoaks losing six of the trees that gave the town its name. What is mentioned far less is the loss of 18 lives.

"When we eventually got him out, he had suffocated under the rubble. They couldn't find a broken bone in his body."

Alec Homewood was about five miles away from his childhood home when its roof fell in and killed his brother.

Cyril Homewood, known as Bob, was upstairs asleep in his bedroom when the chimney collapsed - the force of which pushed the legs of his bed through the ceiling into the kitchen.

"It just devastated the house," his brother said. "Virtually all the roof came down. Mother said he'd been killed, but we didn't know."

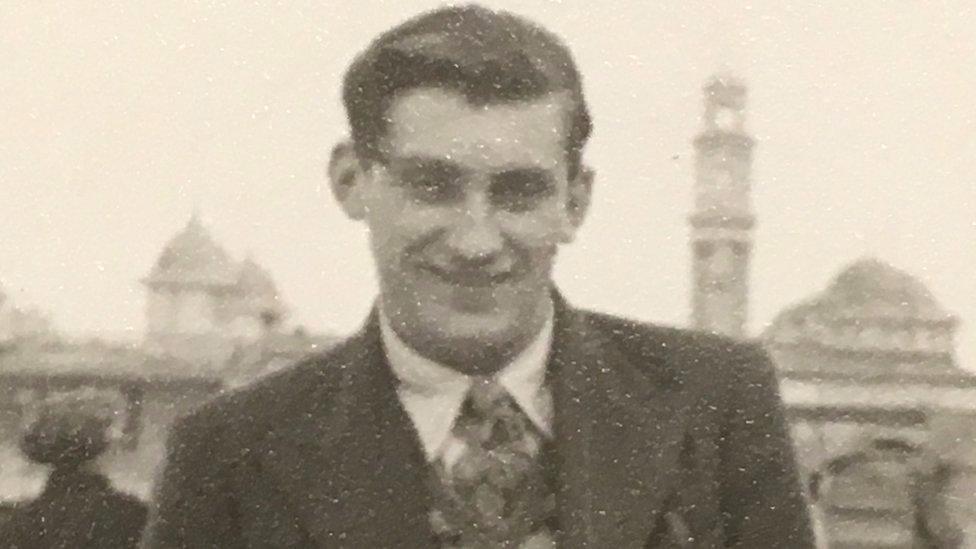

Alec Homewood remembered his brother Bob, pictured, as "a great bloke"

Mr Homewood set out for the house at Biddenden in Kent, but countless trees felled by ferocious winds had made roads around the village impassable.

Using a chainsaw, he hacked at them as he went. When he arrived at Beacon Hill Farm, he found his mother had been rescued from the drawing room by people living nearby.

But when they tried to reach his 59-year-old brother, they found the bedroom was full of bricks and debris.

"It took me ages to get there," Mr Homewood, now 72, remembered. "They [the emergency services] got him out in the end, but he was dead."

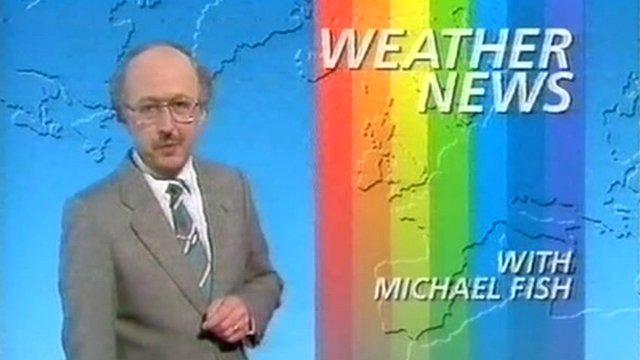

Former BBC weatherman Michael Fish during his infamous weather forecast of 15 October 1987

Severe weather had been predicted before the Great Storm - as it later became known - hit the south coast of England in the early hours of 16 October.

The previous afternoon, the Met Office had forecast winds for the Channel and very heavy rain overland.

The BBC's weather presenter Michael Fish had quashed rumours a hurricane was on the way: "Don't worry, there isn't", he infamously told the nation.

But just a few hours later, the storm changed direction.

Severe weather warnings were issued to emergency responders, including the Ministry of Defence and London Fire Brigade.

But what became the worst storm since 1703 was by that point unstoppable.

Cars were crushed by trees ripped from their roots

The cost of the devastation was estimated at more than £1bn

A maximum gust of 115mph was recorded at Shoreham in West Sussex, while London was battered by gales of up to 94mph.

On the south coast the Royal Sovereign lightship witnessed an average wind speed of 86mph. A ship capsized at Dover and a Channel ferry was driven ashore near Folkestone.

Thousands of homes were left without power for several days, and the damage caused by the storm was put at more than £1bn.

The number of trees lost was estimated at 15 million.

Eighteen people in the UK - and four in France - were killed.

The roof and chimney of Beacon Hill Farm collapsed, killing Bob Homewood

Kent police constable Douglas Stitt was five miles away in Tenterden when he got the call for help.

He said the five-mile drive to Biddenden - normally a 10-minute journey - took them more than two hours.

Trees were strewn across the road every quarter of a mile and a fireman with a chainsaw had to cut through the debris as they went.

Great Storm: The healing power of nature

Michael Fish talks about 'that' forecast, external

When they got there, they found a scene of devastation. The 999 crews knew they were dealing not with a rescue, but a recovery.

"It was beyond that stage," Mr Stitt said.

"We managed to climb through the back door. The whole landing was smashed in.

"It was a case of gradually picking our way over the rubble. It looked like a bomb had hit it."

Bob Homewood was remembered as a "super person" who loved working on his father's farm

The Met Office was criticised for failing to predict the devastating scale of the storm

Though experts agree it was not a hurricane, the country experienced hurricane-strength winds

In the months and years that followed, debate raged about whether the storm had been a hurricane.

Experts agreed it was not by definition, because it had not originated in the tropics.

After an internal inquiry, the Met Office improved its forecasting technology amid allegations it had failed to alert the nation.

For Mr Homewood, the shock of his brother's death did not hit him until days after the storm had passed.

He remains adamant it was a hurricane - even having words to that effect inscribed on his brother's gravestone.

"I'll never ever forget him. I think of him nearly every day," he said.

"When I think back, it was terrible. But you can't defeat nature.

"The Great Storm of 1987 was as bad as having a bomb dropped on the place."

Alec Homewood said he thinks of his brother, Bob, every day

Mr Homewood was not the only fatality of the Great Storm, but media coverage of those killed was limited.

John Dowling, who was deputy editor of the Bexhill Observer, remembers how Ronald Davies died at the Queens Hotel in Hastings when a chimney crashed through the roof.

But the newspaper did not report his death, because it happened outside its patch.

Instead it focused on the community's response, including how a group of people in their 70s went out to clear roads with chainsaws.

"Memories are very selective," said Mr Dowling. "Think of memories of '87 and you have certain images and perhaps people tend to wipe out the nasty bits and remember the silly bits."

Emmetts Garden, owned by the National Trust, lost 95% of its woodland to gale-force winds

The journalist said it was "darned difficult" finding people after the storm. Many had left their houses, and neighbours did not know where they had gone.

He remembered a roof being torn off one property leaving a bedroom open to the sea and sky, an entire penthouse that was swept into a car park, and a rowing boat that ended up in a road, 400 yards from the sea.

"It was all hands to the pump, by everyone who could help. Builders, people, emergency services, it was the Dunkirk spirit."

The Great Storm was later categorised as a one-in-200-year event.

On top of the environmental cost, there was structural damage as trees, ripped from the ground by their roots, crushed houses and vehicles and blocked roads and railways.

Even now, residents and historians agree the loss of an estimated 15 million trees was devastating.

"When we looked and saw the trees, hundreds of years old... that was just heartbreaking," said Biddenden parish councillor, Eileen Cansdale.

"There was structural damage that could be addressed, but the trees couldn't be replaced. It completely changed everything."

Those killed in the Great Storm

Alec Homewood had "killed tragically by the hurricane" engraved on his brother's headstone

Mrs Beryl Agha, Hove

John Barton, Petersfield

Patricia Bellwood, Wrotham

David Birch, lost at sea

Sylvia Brown, Canvey Island

Anthony Burton, Salisbury

Ronald Davies, Hastings

Robert Doke, Croydon

Robert Homewood, Biddenden

Ronald Horlock, lost at sea

David Gregory, Christchurch

Terence Marrin, Lincoln's Inn Fields

James Read, Hastings

Sidney Riches, Kings Lynn

Sosammi Shilling, Chatham

Georgina Wells, Haywards Heath

Graham White, Christchurch

Source: Windblown, by Tamsin Treverton Jones

Historian Bob Ogley said news of the loss of life emerged only in the days after the storm because people in the area were still without power.

"There was no radio communication, because most people used electric radios, and there was no TV at all.

"It was only later we learned people had died."

Cars and houses were crushed by falling trees

A light aircraft was blown upside down in Essex

He said people remember the damaged landscape more than anything else.

"Here in Sevenoaks, we lost our name. Sevenoaks was reduced to one oak.

"Most people went to bed and woke up and found a tree in their garden.

"So, people think about the countryside. People don't think about those who died, because they were spread over a large area.

"Having said that, every death is a tragedy."

See more about the Great Storm on Inside Out, on BBC One South East, South West and South on Monday 16 October at 19:30 BST, and later on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published15 October 2012

- Published15 October 2012

- Published15 October 2012

- Published14 October 2012