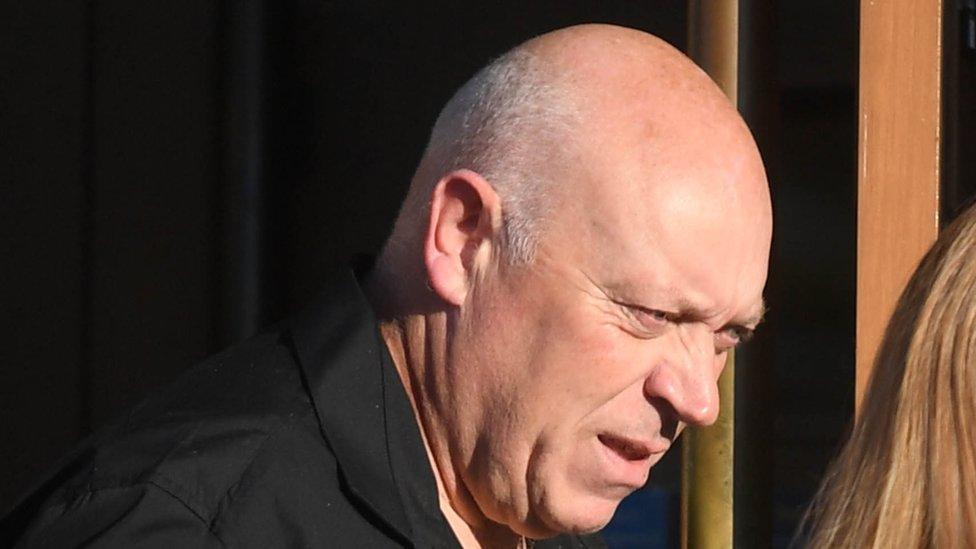

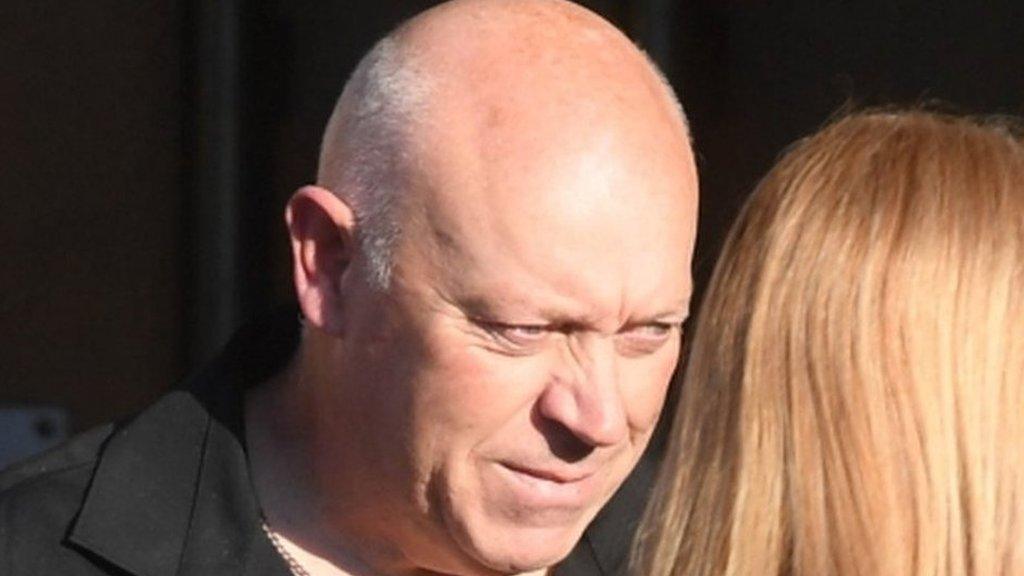

Andrew Griggs: The wife killer who escaped justice for 20 years

- Published

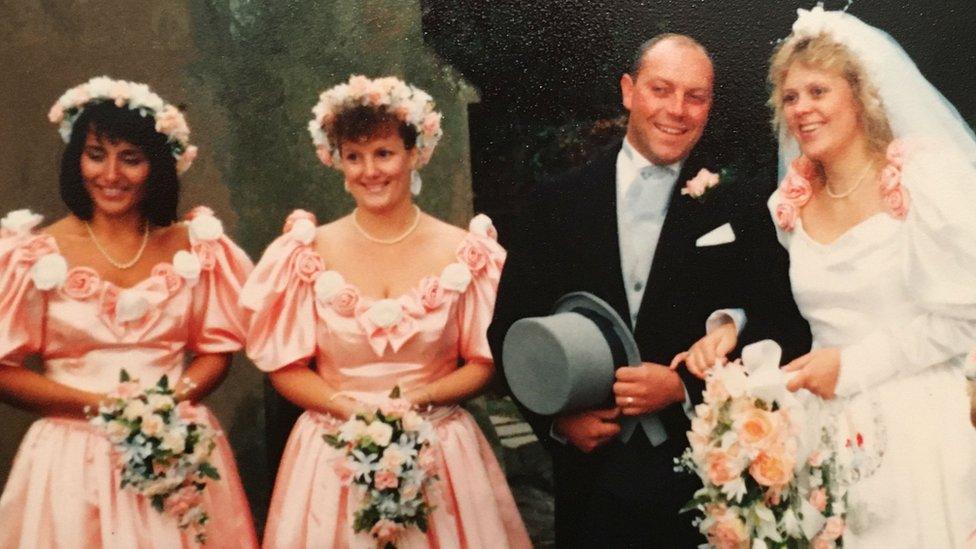

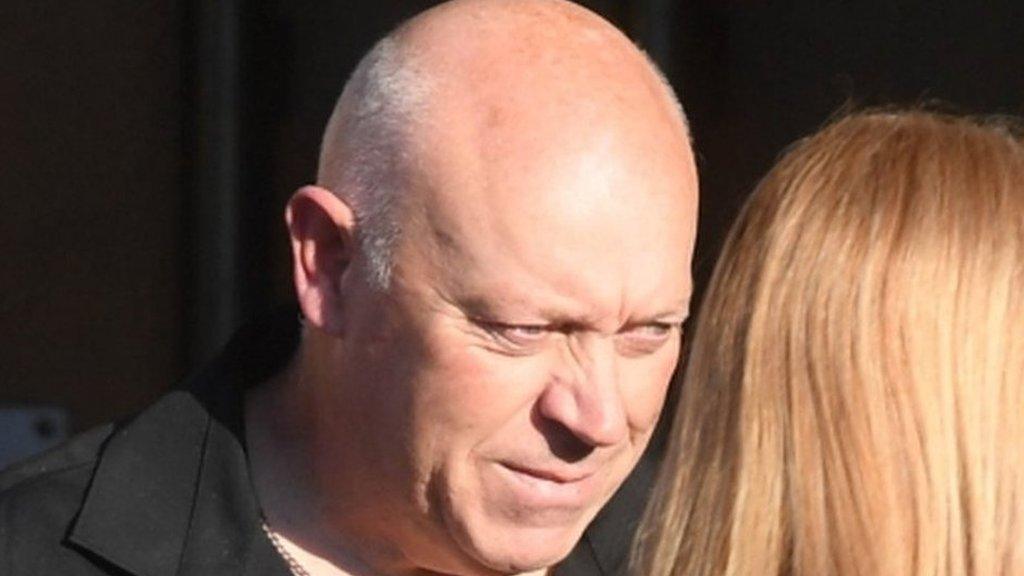

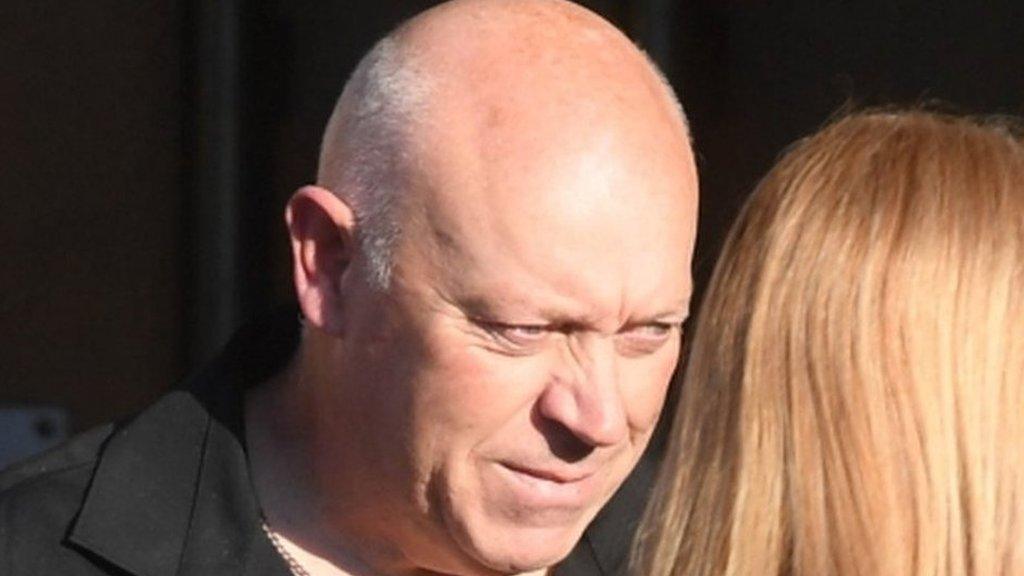

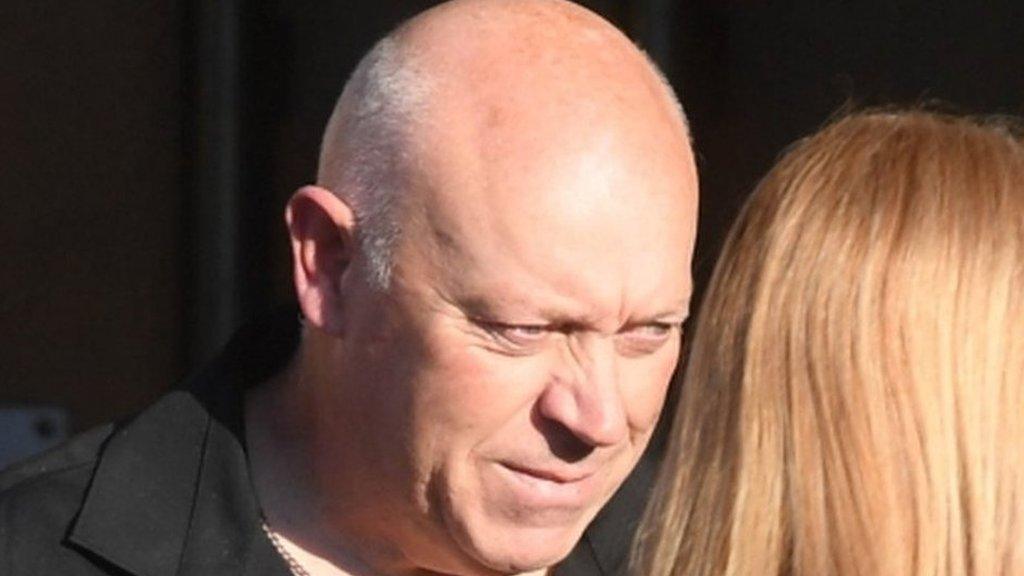

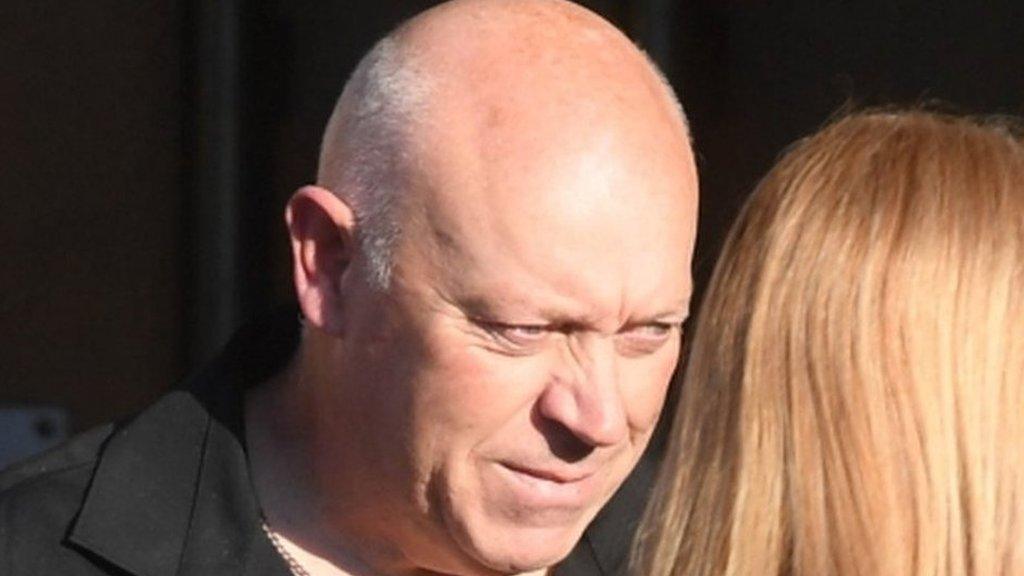

Debbie and Andrew Griggs were married for nine years before she disappeared

For 20 years, the disappearance of Debbie Griggs remained a mystery. Two decades later, her husband has been convicted of her murder and jailed for a minimum of 20 years. What changed?

The answer is actually almost nothing.

When 57-year-old Andrew Griggs entered the dock earlier this month, accused of killing his wife and disposing of her body on 5 May 1999, he faced the same weight of evidence that prosecutors had decided in 2003 offered "no realistic prospect of conviction".

Det Supt Paul Fotheringham, who leads the major crime unit in Kent, did point out that the passage of time helped undermine her husband's claim that 34-year-old Mrs Griggs had walked out of her own accord: there had been no sign of her on any government system in the two decades since she was last seen at the family home in Walmer, Deal, in Kent.

Similarly, the idea that she could have taken her own life became less plausible over the years, because there was no trace of a body, despite exhaustive international searches and DNA testing of unidentified female corpses.

But beyond this, nothing had changed. A central plank of the prosecution case was that Griggs killed his wife because he was having sex with a 15-year-old girl, yet police knew about this abusive relationship in 2003. The teenager, now a woman in her 30s, gave evidence for the prosecution, telling jurors that Griggs had groomed her at a time she was vulnerable.

Andrew Griggs claimed his wife had abandoned their young family

Det Supt Fotheringham, who was a young beat officer in Deal at the time of Mrs Griggs's disappearance, said he had always believed Griggs had killed her and that the case had remained in "the forefront of my mind".

In 2018, by now in charge of the cold case team, he hired a retired detective to review the Griggs file and told him: "Just go over it again in today's context."

For Sarah Dineley, of the Crown Prosecution Service, the decision eventually to charge Griggs with murder is explained by prosecutors reassessing the "significance of parts of the evidence".

For many in Deal, where Mrs Griggs's family had lived for generations, there was only ever one answer to the mystery: Griggs, a keen sailor from a family of fishermen, had, they believed, murdered his wife and disposed of her body at sea.

However, the case was initially treated by police as a missing person inquiry, with Griggs only arrested for the first time 20 days after his wife's disappearance.

He remained the prime suspect throughout a four-year investigation, but police struggled to dispel the feeling they had been slow off the mark. Mrs Griggs's mother, Patricia Cameron, said in 2003 that police seemed to be "dragging their tails".

Helen Cheeseman, who was Mrs Griggs's best friend from the age of 12, said police had been "misdirected" by Griggs's claims his wife had depression. "That's why they were looking for a missing person," she said.

Griggs spent many hours at the Downs Sailing Club in Deal

Griggs mentioned depression within 30 seconds when, 24 hours after he claimed she had stormed out, he phoned police to report his wife missing. When concerned neighbours inquired as to her whereabouts, he said she had been behaving like a "madwoman" and had "not been taking her pills".

Long before he murdered his wife, Griggs had begun to do the groundwork. He told family and medical professionals that she was buckling under the weight of her depression. Mrs Griggs wrote in her diary that her husband accused her of being "sick and mad in the head".

And yet, as her GP Dr Peter Schouten told the jury at Canterbury Crown Court, she had "displayed none of the signs or symptoms of depression" in the weeks before her disappearance. Mrs Griggs had experienced postnatal depression after the birth of her first two sons, but not her third, born in 1997, he told the jury.

Gossip was "rife" in Deal after Mrs Griggs disappeared, Canterbury Crown Court heard

According to Mrs Dineley, our understanding of mental health issues has "changed greatly over the past 20 years".

Asked if prosecutors had considered the public's shifting attitudes when making a decision to charge Griggs, she said that "if we look at acceptable behaviours, norms, 20 years ago and where we are now, they are very different".

Speaking before the trial, Mrs Dineley said: "Those changes in attitudes hopefully will allow the jury to see this for what it is: a man who is trying to lay the blame at his wife's door to try and cover up his actions. I obviously can't get inside the minds of jurors, but they will of course be judging it on today's standards."

Helen Cheeseman (next to Griggs) was one of her best friend's bridesmaids

Davina James-Hanman, who has spent a 30-year career trying to improve the prosecution and prevention of domestic abuse, currently conducts domestic homicide reviews for the Home Office.

There has been a "process of massive change" in the criminal justice system's treatment of domestic abuse, she said. The 2003 decision not to charge Griggs was "just on the cusp" of this shift, she said.

Ms James-Hanman, a trustee of the Centre for Women's Justice, was part of a wide-ranging review of the "inadequate" way police and prosecutors handle domestic violence cases, external, published in 2004. "From that moment on things really started to shift. For the first time ever, prosecutors received domestic abuse training."

Griggs's attempts to question his wife's sanity, would, she said, be "scrutinised more closely these days because we know how manipulative abusers can be". Public understanding of domestic abuse has also improved, she said.

'A wonderful mother'

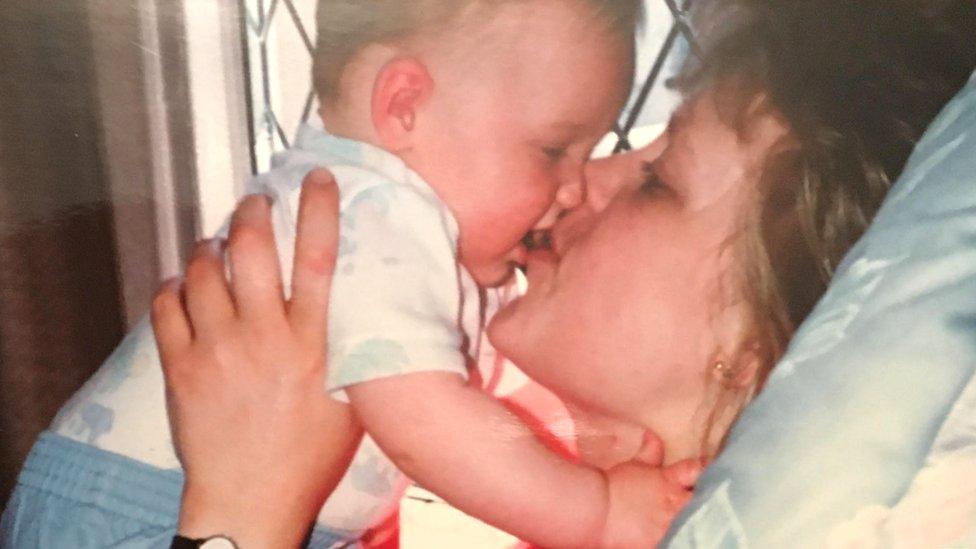

Mrs Griggs was devoted to her three sons, the jury heard

Deborah Elizabeth Cameron was born in December 1964, the eldest daughter of a large and loving family with deep roots in the seaside town of Deal.

At school, she was well liked and "game for a laugh," her childhood friend Helen Cheeseman said, recalling how she once joined in a mud fight during an outdoor science class. Mrs Cheeseman said Debbie, who was godmother to her daughter Samantha, "just loved children", adding: "She had the patience of a saint."

She trained as a nurse, working first at the Kent and Canterbury Hospital and later looking after disabled children. When her own children came, the first in 1992 and two more within five years, she grew into a "wonderful mother," Mrs Cheeseman said. "She had that motherly instinct in her."

"Debbie would never have walked out on her children," her friend said. In May 1999, Mrs Cheeseman's son Barry was diagnosed with cancer for the second time. "She knew he was ill. She wouldn't have gone and not ever have contacted me."

Marian Duggan, a senior lecturer in criminology at the University of Kent, makes a similar case.

Asked if prosecutors would have considered changes in the way jurors might interpret evidence, Dr Duggan said it was likely the case against Griggs "would be considered differently by juries today than it would have been 20 years ago".

This was, she said, "because of the greater knowledge we have around domestic violence victims and perpetrators' attempts to rely on these cultural stereotypes that cast doubt on the credibility of the victim - the mad, sad, bad thing".

Debbie Griggs with Mrs Cheeseman's son Barry

"We just want the truth to come out," said Mrs Cheeseman, who fears her friend's body will never been found.

And although such cases are rare, it is estimated there are about two "no body murder" trials in England and Wales each year.

Indeed while Griggs was on trial, a different jury was considering evidence against another Kent man who is accused of murdering the mother of his children, despite the fact her body has never been found.

Helen Cheeseman said she was "robbed of her best friend"

It is illegal in the UK to ask jurors about how they arrived at their verdict, so it will never be known how they reached the decision that Griggs had been lying about his wife's death for 20 years.

In a 2003 TV appeal, Patricia Cameron said that, while she always knew what had happened to her daughter, she desperately wanted it to be "made public", so she could "close a chapter in my life and hopefully turn a page and start living again".

Progress came too late for Mrs Cameron, who died in January, just a few weeks before her daughter's killer was charged.

Mrs Cheeseman said: "She died broken-hearted."

Kent Police said in a statement: "Debbie's disappearance was initially investigated as a missing persons inquiry, as was appropriate and proportionate given the missing person report and lack of any evidence at the time that she had come to harm. It was through the inquiries carried out that led officers to suspect she had died and the investigation was then handed to Major Crime detectives who launched a murder investigation and arrested Mr Griggs."

- Published30 October 2019

- Published28 October 2019

- Published21 October 2019

- Published18 October 2019

- Published17 October 2019

- Published10 October 2019

- Published9 October 2019

- Published3 October 2019