Teenage suicide: Bereaved siblings fight mental health 'stigma'

- Published

Every few weeks, Sophie Fagg visits her sister Lucy and shares the latest twists and turns in her life - including the details that would likely have been used as ammunition for gentle, sisterly jokes.

"She liked to make fun of me, as sisters do," she said, standing by Lucy's grave in Sturry, Kent.

The "bubbly" 16-year-old, who was an avid Liverpool fan and competitive angler, took her own life in March 2020.

For Sophie, then aged 19, life changed forever in an instant. Daydreams of dropping future children with "fun aunt Lucy" disappeared.

Regular trips to the local cemetery became the reality.

"I like to chat to her, to let her know that she's still in our hearts," Sophie said.

One year on, her emotions are still a mixture of guilt, pain and anger - both at herself and, less often, her sister.

"I told my sister off at her funeral," she said. "I've got a little bit of anger at Lucy, because I'll never quite understand it."

"You've got this pain that will never go away that you weren't able to help the person that you love," she said.

Sophie Fagg said her "bubbly" sister Lucy loved to make jokes

Rates of suicide among young people have "generally increased in recent years," but the overall numbers remains low, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) says, external. The deaths of 601 under-25s were recorded as suicides in England and Wales in 2019, compared to 434 ten years earlier.

The rise was particularly clear in females aged between 10 and 24, for whom the rate per 100,000 rose from 1.6 in 2012 to 3.1 in 2019, the ONS said. Over the same period, the rate for males of the same age rose from 7 to 8.2.

Last week, the government said £79m would be spent to increase mental health support for children and young people, including capacity to help an extra 22,500 people.

If you are experiencing emotional stress, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line here.

Paul Farmer, of mental health charity Mind, welcomed the extra funding, and said that many children faced problems accessing support even before the pandemic, which had "disproportionately affected younger people".

Sophie believes swift professional support would have saved her sister's life.

"If she got the help that she needed, I'd still have my little sister to go home to everyday," she said.

Sophie hopes speaking publicly about her sister will encourage people to get help and break a "weird stigma about talking about mental health".

"I've got this fire in me to make sure that nobody else feels the way that I do," she said.

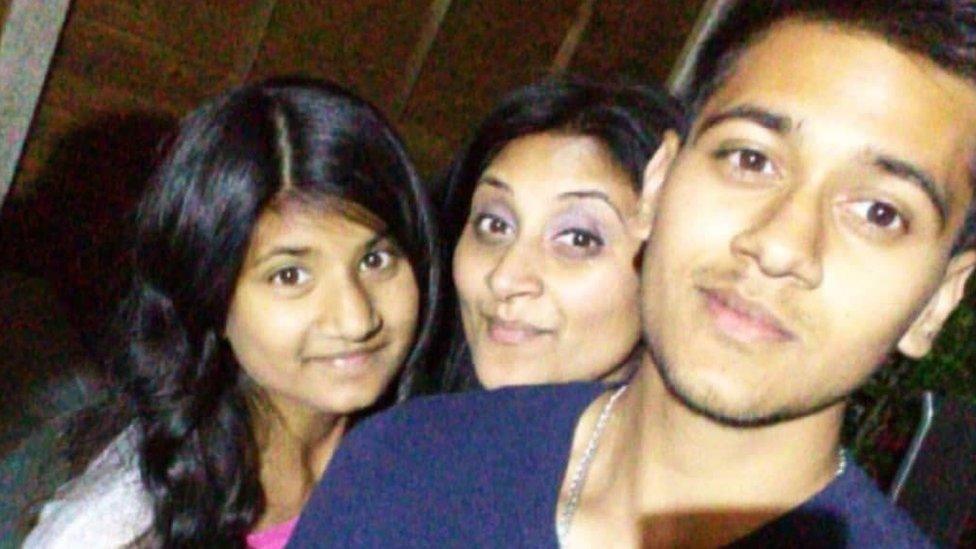

Sapna Patel with her mother and brother

Sapna Patel was just 14 when her 19-year-old brother, Sadil Narayan, ended his life.

"I cry nearly every single day, because I miss him so much," she said.

Four years later, she too hopes that sharing her story will help others.

"I want to give a positive message: 'Please reach out to someone as you are not alone. I lost my brother and I wouldn't want anyone to go through this.'"

At first, her sadness was tinged with anger.

"I'd miss him so much, I'd feel like he abandoned me," the 18-year-old, from Edgware, north London, said.

Seeing other people with their siblings triggered feelings of jealousy and memories of their tight bond, forged over hours of Xbox games and trips in his car.

"He loved cars so much," she remembers. "That was his favourite hobby."

Sapna was just 14 when her 19-year-old brother died

In the years since, Sapna said she became increasingly withdrawn, wary of forming close friendships that might lead to questions about her brother.

"I isolated myself from a lot of people," she said. "With friends, I try and stay away from them because I don't want to talk about my situation."

With the help of therapy, she is determined to end her self-enforced isolation. When she returns to college as lockdown eases, she is prepared for any questions from the new friends she hopes to make.

"If people ask me how many siblings do you have, I say I used to have a sibling, but he is not here anymore. I just say I don't want to talk about it, otherwise it's going to make me upset."

Ben West, right, with his brother Sam

Ben West's drive to improve awareness and treatment of mental health issues has reached many highs, including an appointment with the prime minister and a Pride of Britain regional award.

It began when his 15-year-old brother Sam took his own life in the family home in Cranbrook, Kent, in January 2018.

The cycle of emotions triggered by the shock, trauma and grief was "like being put into a washing machine," he said.

"It will go and then it will stop, and then you'll have a different phase of the cycle. It's totally confusing, disorientating, claustrophobic."

How to help

If you're worried someone is suicidal, asking them directly can help, the Samaritans say.

There are some signs to look for:

Appearing tearful, agitated or angry. Lacking energy, avoiding talking or not doing things they usually enjoy

Using alcohol or drugs to cope with feelings, or finding it hard to cope with everyday tasks

Talking about feeling hopeless, helpless or worthless, or feeling trapped or unable to escape their thoughts

In the weeks after his brother's death, he received hundreds of messages from people sharing their stories and he thought to himself: "How can all of these people be suffering in the same way, and none of them know they're all suffering in the same way together?"

Sam had been diagnosed with depression in September 2017. Despite having an amazing group of friends, who Ben knows would have been understanding, his brother did not want to share his struggles, he said.

"In hindsight knowing what he was dealing with and me as an older brother not understanding that at the time, I just wanted to do my best to stop this from happening to somebody else," he said.

Despite the strides forward in awareness, and public outpourings at key dates like World Mental Health Day, many people still feel hesitant to speak out, he said.

"Publicly, everyone is supporting this, but there's still a stigma."

Ben West said campaigning had helped him cope with his brother's death

The 20-year-old, who is studying aeronautical engineering at university, says the campaign has helped him carry on through the grief.

"I couldn't be functioning as a person if I wasn't doing this. I'm still going through the death of my brother. I still need to cope with that. So for me, this positive that I can bring out of it has been just invaluable to coping with that."

While he was helped by a "lovely group of friends and an amazingly supportive family", he feels more should be done to help siblings bereaved by suicide, with a greater emphasis on therapy.

"It's taken me three years to actually go and see a counsellor, because I've had to go out of my way to go and find out about that," he said.

"If someone had actually sat me down and said let's get you involved in this, that could have saved me so much pain in the last few years."

Follow BBC South East on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to southeasttoday@bbc.co.uk.