Battle of the Somme: Why are the Accrington Pals famous?

- Published

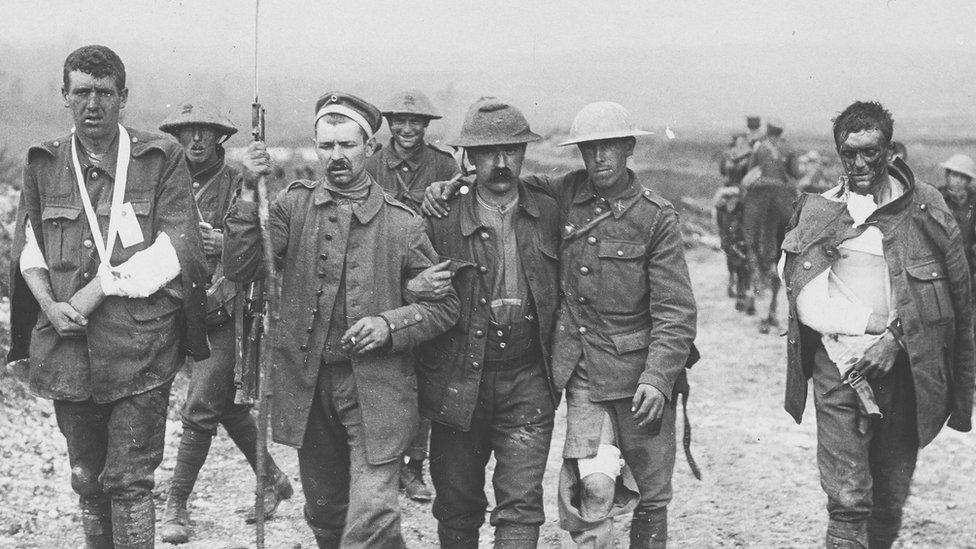

Soldiers from Lancashire in the trenches during World War One

Among the battalions of British volunteers who fought at the Battle of the Somme, one name often attracts greater attention - the Accrington Pals. But why are they so well known?

Following a rallying cry by War Secretary Lord Kitchener, battalions were formed across the country, including in the east Lancashire town of Accrington where about 1,000 men signed up.

"It's gone down as being the smallest town or borough in Britain to raise a complete battalion," explains local historian Andrew Jackson.

A reference to the Accrington Pals in Martin Middlebrook's historical account The First Day on the Somme caught the eye of the late dramatist Peter Whelan, who was then inspired to write a play about the battalion that debuted in 1981.

It explored the impact on a town when men went to war, with the women left behind, homing in on the unrequited love between fictional soldier Tom and his second cousin May.

Pte William Marshall signed up for the Accrington Pals and survived the war

Accrington Pals

Nearly half the recruits were from the neighbouring towns of Blackburn, Burnley and Chorley, and together they formed the 11th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment

The Pals later joined battalions of the York & Lancaster Regiment to form the 94th Brigade, 31st Division

In January 1916, they arrived in Egypt to provide a guard to the Suez Canal - controlled by the British and French - against the Turkish army

They later took part in the British-French attack near the River Somme on 1 July 1916, when their goal was to capture the hilltop fortress of Serre

At the end of the Accrington Pals' first major action - on the first day of the Battle of the Somme - at least 584 of the 720 troops who took part were killed, wounded or missing.

Pte William Marshall, who survived the fighting, recalled many were "killed and wounded even before they could get out of their trenches".

Rumours reached Accrington a few days later, prompting a group of women to gather around the mayor's home, demanding the truth.

In his preface to the play, Whelan, keen to write about working-class women during the war, noted: "For me this was like looking through a pinhole into the past and finding a whole vista of humanity revealed in a very unexpected way.

"These mothers, wives, daughters and lovers of the Pals didn't knuckle under sheepishly to authority in the way I had supposed."

Peter Whelan's play The Accrington Pals was staged at Manchester Royal Exchange in 2013

Wendy Lawrance, who specialises in World War One literature, says: "It wasn't a big town in the first place so it was one of those areas where you were looking at every single family being affected."

Percy Holmes, the brother of a Pal soldier, recalled: "I don't think there was a street in Accrington and district that didn't have their blinds drawn, and the bell at Christ Church tolled all the day."

Now on a syllabus for A-Level students, Whelan's play has helped keep the story of the Accrington Pals alive 100 years on.

"You've got characters in there who, even now, people can relate to "because you've got your political idealist in Tom and your ambitious individualist in May," says Lawrance.

"At the end of it, neither of them really wins, they both lose - Tom loses his life but May loses Tom.

"May's attitude to the war had been 'It's not my problem, I'm going to stand back from this' and Tom's attitude to the war had been 'We need to do the right thing and help'... and I think that's quite relevant especially at the moment."

The Accrington War Memorial has recently been upgraded to Grade II listed status

Drama lecturer John Davey, who knew Whelan, doesn't believe it was the fact that Accrington was the smallest town to raise a complete battalion that made its Pals renowned. "As far as I read it... Peter's play raised the profile of the whole Pals phenomenon very significantly."

The term "Pals battalions" was coined by Edward Stanley, the Earl of Derby - a Lancashire aristocrat who was the government's director of recruiting. He thought more men would enlist if they could serve with their friends and neighbours.

"I guess the effects of the Pals regiments was that the government [later] changed its policy and made sure that people from different areas were put together in the battalions," says Mr Davey.

"So it was a tacit acknowledgement of the fact that, while this had been a very clever recruitment strategy, in fact it had reaped a terrible whirlwind in the effect on local communities.

"I don't think Peter consciously thought of the play as symbolic but it was certainly representative of what was going on."

A wounded German prisoner of war assists injured British soldiers at the Somme

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916, it was an operation between British and French forces intended to achieve a decisive victory over the Germans on the Western Front

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day but 19,240 British soldiers lost their lives - making it the bloodiest day in the history of the Army

By the time the battle ended on 18 November 1916, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence

In total, there were more than a million dead and wounded on all sides, including an estimated 465,000 from Germany, 420,000 British and about 200,000 from France

Find out more:

- Published1 July 2016

- Published29 June 2016