Hoarding: 'I want a tidy life, but I can't do it on my own'

- Published

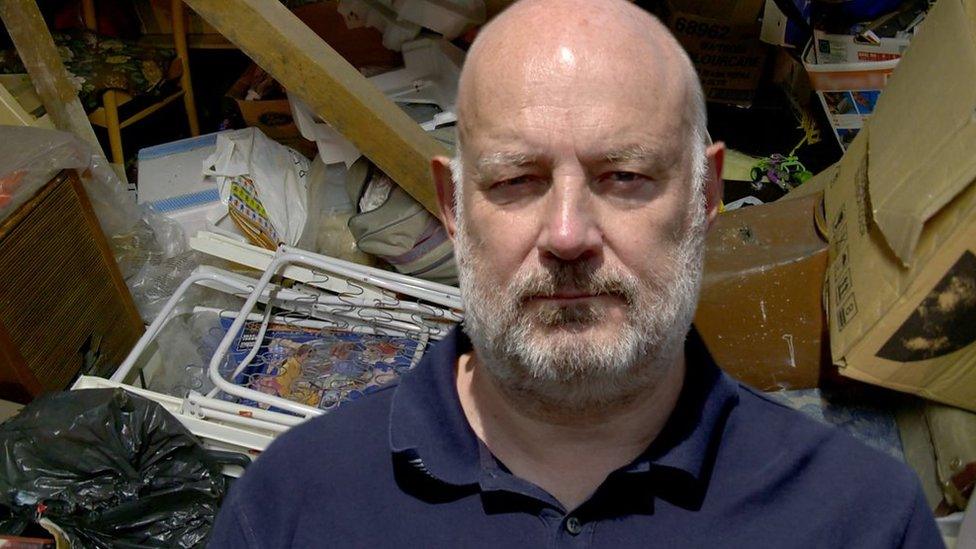

Edward Brown says he gets "a buzz out of supporting hoarders and seeing people have better lives"

Having a hoarding disorder has caused Edward Brown "overwhelming psychological distress".

His Blackburn home is packed with a chaotic mix of household items and bric-a-brac - jars, tins, cups, cuddly toys, CDs and an array of bags and boxes, some already overflowing and others waiting to be filled.

The 60-year-old says he can no longer welcome in visitors, as there is "no room for people to move when they come".

He says the disorder is "often caused by trauma [and] I've been through various traumas myself" and that trauma leaves people "with the after-effects of what has happened to you".

"My mind works different; there is something not right somewhere in my thought processes," he says.

But while he understands the reasons why he hoards, dealing with the issue is difficult.

He admits that "collecting stuff can get out of hand", but says the stress of living with the disorder can leave him in "a 'leave me alone' mode".

However, that does not mean he wants to accept the situation and to that end, he has helped to set up a peer support group in the Lancashire town, which aims to aid those living in similar conditions.

He says he gets "a buzz out of supporting hoarders and seeing people have better lives".

A council and charity-backed scheme is working with hoarders to help them deal with the issue

The pilot scheme has been put together by Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council in partnership with the charity Hoarding UK.

The council's neighbourhood manager Michelle Rutherford says hoarding is "a big issue in the borough, but a lot of it is hidden".

She says that while extreme hoarding can lead to homes which are "unclean, unmanageable... and pose a fire risk, the monthly support sessions are "non-judgmental".

"There are lots of different reasons why people hoard," she says.

"Simply clearing a house does not deal with the issue and can be very traumatic for those affected."

Hoarding disorder

A hoarding disorder is where someone acquires an excessive number of items and stores them in a chaotic manner, usually resulting in unmanageable amounts of clutter

Hoarding is considered a significant problem if the amount of clutter interferes with everyday living or it is causing significant distress or negatively affecting quality of life

Hoarding disorders are challenging to treat because many people who hoard frequently do not see it as a problem, or have little awareness of how it's affecting their life or the lives of others

Source: NHS, external

Edward says taking drastic action and issuing deadlines "just piles on the pressure".

He faced the threat of eviction eight years ago when a heating engineer reported his flat as a fire hazard.

"The fire brigade came round and [the officer] said 'all this has to be sorted in two weeks'," he says.

"She came back two weeks later and she said 'it's still the same'.

"I'd cleared some stuff but she said it wasn't enough.

"She was convinced I could do it all in two weeks."

He says his psychiatrist later told him the ultimatum was "totally unrealistic".

Carl Molyneux says before he got help, he "held on to loads of tat"

Lancashire Fire and Rescue Service has since changed its approach.

The service's hoarding lead Kirsty McLoughlin says while it can cause a "massive fire risk" in homes, simply getting rid of items or being ordered to clear them quickly can be "retraumatising".

"We're now tailoring our advice to make sure people are as safe as possible," she says.

"We don't know what has led to that situation [and] we don't want to judge."

She says that when carrying out fire risk assessments now, the service try to put emergency escape plans in place and check if there is anything that is unsafe in the house.

She says they can also provide a "bridge" to other organisations who can offer support.

Carl Molyneux runs one such support scheme.

If you're affected by the issues in this piece, you can find support from BBC Action Line.

As the manager of Colne's Elisha House, he helps people who have a history of substance abuse - and as a former hoarder, he says he sees a clear link between hoarding and compulsive behaviour.

"The first thing I remember collecting was lolly sticks," he says.

"I don't think I ever even used to do anything with them; I just collected them and they became a bit of an obsession."

That spiralled into other items, such as beer mats and "literally hundreds of lighters", until he was surrounded by "boxes and boxes of stuff".

He says he probably collected to boost his self esteem and thought "if I've got this stuff, I'll feel a little bit safer or better about myself".

"I was not even aware of it until I went in rehab and people were talking about obsessive compulsiveness and how it relates to addiction," he says.

"I thought back to my childhood and started connecting the dots.

"I held on to loads of tat."

NHS guidance on hoarding disorder states it can be associated with a number of mental health conditions, such as sever depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia.

Where are you on the 'clutter scale'?

Carl says when he left prison and stopped using drugs, he saw it all through "a new set of eyes".

"My brother was quite similar to me [in that he] collected lots of stuff and I remember seeing all this stuff and thinking: 'That needs to go in the bin'.

"It was much easier for me to throw his stuff away than my own."

For Edward, the process of throwing things away has been difficult, but he says he is getting there using Hoarding UK's Clutter Index Rating, external.

"It has a scale of one to nine," he says.

"One is no clutter at all and nine is when you are piled up to the ceiling.

He says his flat is "a level five or six in some areas", but he has "agreed to get my clutter down to a level four".

"I don't want to live like this forever," he says.

"I want a nice life, a tidy life, but I can't do it on my own."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published29 August 2021

- Published16 May 2021

- Published9 February 2020