Nelson Mandela: A fellow Robben Island prisoner's memories

- Published

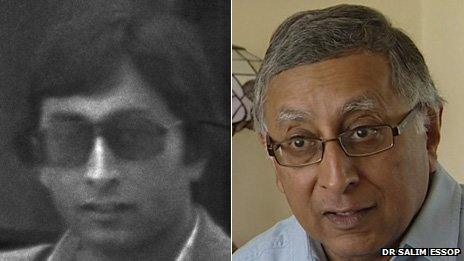

Dr Salim Essop pictured in Leeds in the early 1980s - after his release from Robben Island prison - and as he is today

The first sight Dr Salim Essop had of South Africa's infamous Robben Island jail was as he emerged in chains from the freezing bowels of a prison ferry after a rough midwinter crossing from Cape Town.

Sentenced to five years imprisonment for political offences against the state in November 1971, the 21-year-old former medical student at Wits University in Johannesburg had just been moved from a short stay in a Pretoria jail.

Dr Essop's destination was already well-known to him as the home of political prisoner Nelson Mandela, first jailed in 1962 as one of the leaders of the struggle against apartheid - enforced racial segregation - in South Africa.

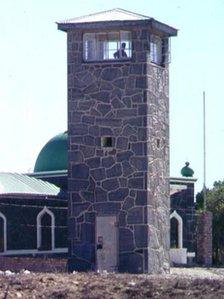

Robben Island prison was home to many political prisoners during the apartheid regime

Dr Essop's crime was to have been an underground activist, working illegally with the outlawed African National Congress (ANC) - the party of Mandela - and other organisations hoping to end apartheid.

On 21 October 1971, Dr Essop's political activities were discovered by police after he, along with fellow activist Ahmed Timol, was arrested at a roadblock and taken to John Vorster Square police station in Johannesburg for questioning.

"We were very seriously and badly tortured on the 10th floor of the building," said Dr Essop, who is now an academic, photographer and writer in Leeds.

"We were very badly tortured. I ended up in a coma. My friend was killed during the torture."

Dr Essop - who could not walk or talk for some time after his experiences at John Vorster Square - was imprisoned, first in Pretoria then on Robben Island, after a trial lasting almost a year.

"For some reason the authorities decided I might be a serious troublemaker, so they decided I should be kept in the Leadership Section where they kept certain people away from the rest of the political prisoner community," said Dr Essop.

It was in that Leadership Section at Robben Island that Dr Essop first rubbed shoulders with the likes of Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada - all of whom would go on to become major figures in the post-apartheid South Africa in the 1990s and beyond.

Dr Essop was immediately impressed with Mandela.

"He always carried himself with enormous dignity and he was a commanding personality there," he said.

"The warders almost had to look up to him - he had that kind of presence. He was not a man you could talk down to or abuse.

"He was a very serious, formidable person as far as the authorities were concerned, so they actually treated him with great caution."

Dr Essop said he looked up to Mandela and the other leaders as father figures. They, in turn, treated him with "warmth and loving care".

"We were a very close community. We lived as a family. We were friends with one another," he said.

Mandela always made sure he took care of himself and was a "terrific physical presence" in the prison, said Dr Essop.

"He always exercised, even on Robben Island. He always did a sprint every morning and he exercised in his cell.

"He always had an athlete's body. He used to be a boxer and he used to talk about boxing."

But most of all, said Dr Essop, Mandela was a teacher, a mentor and "a man of ideas".

"He was always a thinker for tomorrow. He would be thinking about what we have achieved so far, but also what we can still achieve tomorrow. He had a visionary quality."

Dr Essop revisited the prison in 1997 and is pictured outside his old cell

While Dr Essop was released from Robben Island in 1977 - heading to England to take up his studies in politics and law at the University of Leeds in 1981 - it was to be another 13 years before fellow prisoner Mandela would taste freedom.

Dr Essop said seeing his friend walk out of prison was one of the greatest moments of his life, marking "a new era and a new world in South Africa".

Mandela went on to become president of South Africa in 1994 and was a major figure on the world stage for many years before his death.

While the South Africa Mandela has left behind might not be exactly as he would have wanted it, his future vision of the country is still attainable, said Dr Essop.

"Even if certain things haven't been achieved and if things have gone pretty badly in South Africa - and some people are extremely disappointed and disillusioned by the new South Africa with what has happened in the last few years - the vision that Mandela had is not lost," he said.

"If you ask me what is his legacy, it's that vision of a new South Africa - a united rainbow nation with everybody living together."

- Published8 June 2013