The child immigrants 'bussed' out to school to aid integration

- Published

In 1960s and 70s Britain, immigrant ethnic minority children were dispersed across schools in the hope that it would help them integrate.

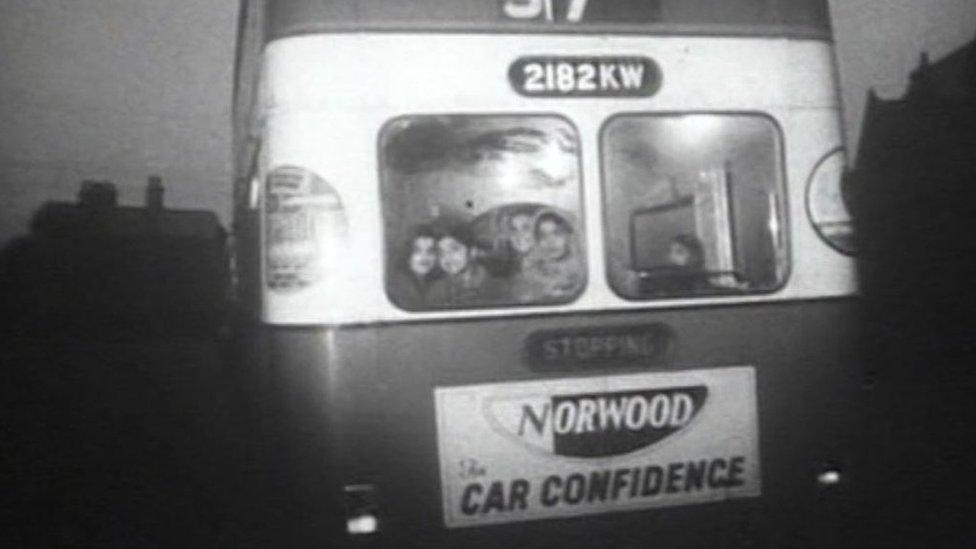

The process saw children - largely of south Asian and African or Caribbean descent - being "bussed" out of their local areas to go to school.

Eleven Local Area Authorities (LEAs) decided there should be no more than 30% of immigrants at any one school.

It meant once that quota was reached, children were taken elsewhere.

The process, which became known as "bussing", is now at the heart of a project in Bradford where Shabina Aslam is trying to trace children, external who, like herself, were sent to school away from where they lived.

She moved to Bradford, West Yorkshire, from Kenya when she was seven years old. She remembers how the buses were marked so the children knew which one to get on.

"We were all told to look for signs, like a yellow sun, black football, or a red diamond," she said.

Some of the children who were bussed said they were educated in different parts of the school

"So you'd wait for your red diamond bus, you'd get on it, you'd get to school and suddenly it was the 'Paki bus'."

She said the practice made her and the others who were bussed feel more segregated, instead of integrated.

Raj Samra, who was a 1960s child bussed in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, said there was a key flaw in the plan which stopped pupils integrating properly.

The scheme was set up to help migrant children integrate with others

"We were in an annexe of the main school, so we weren't mixing," he said.

"Had we been in another school mixing with all the other children, then the project would have worked."

It was a plan conceived at a time when large numbers of Asian and Afro-Caribbean families were heading to the UK. Many of them could not speak English and the LEAs came up with this as a solution.

The councils that adopted a bussing policy were: Blackburn, Bradford, Bristol, Ealing (Southall), Halifax, Hounslow, Huddersfield, Leicester, Luton, Walsall and West Bromwich.

Speaking in 1979, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council's director of education Frederick Adams said: "The idea is to put the children from overseas in a situation where they have to mix, and if as is the case in this city, about 75% of them are non-English speaking when they arrive, this means they are going to have to communicate, they will hear English spoken, they have got to."

Bussing took place in West Yorkshire between 1965 and 1980

By then, Bradford was sending out 24 buses a day, but in Ealing, west London, campaigners had challenged bussing in court claiming it fell foul of the new race relations legislation.

Brenda Thomson was a teacher in Bradford when bussing was the norm. She said it was done "with the very best of intentions".

"It was assumed that the children would learn English better in a naturally English-speaking environment," she said.

"Which is OK if you speak to your mates in the classroom, but if you don't it doesn't help very much does it?"

Mohammed Ajeeb organised a petition to get bussing stopped in the late 1970s, saying the practice was racially motivated.

Shabina Aslam is studing the practice of bussing in West Yorkshire

"In March 1979 a petition was presented to the then chair of the education committee signed by 1,600 parents that demanded the end of bussing.

"It was one-way traffic. Only children from the inner-city areas, the black children, were being bussed into the middle-class areas."

In 1980 Bradford became the last place in the UK to phase out bussing for good.

Mrs Aslam believes that although some had positive experiences of bussing and said they enjoyed school, it made her and many others feel more isolated.

"We'd walk in late in a group and we'd always have to leave early. The bus monitor used to come round and say 'can we have all the immigrants please?' and all the black children would stand up," she said.

"I didn't really have any friends in the classroom, nobody ever spoke to me.

"I was always looking at the others thinking: 'how do I become like them?'"

- Published11 March 2016