BME communities face 'cultural taboo' over mental health

- Published

One woman's battle with post-natal depression

People from black minority ethnic (BME) groups are hiding mental health issues because of cultural stigmas about the condition, it is claimed.

Charities said expectations on how to behave and family honour stopped some women speaking out.

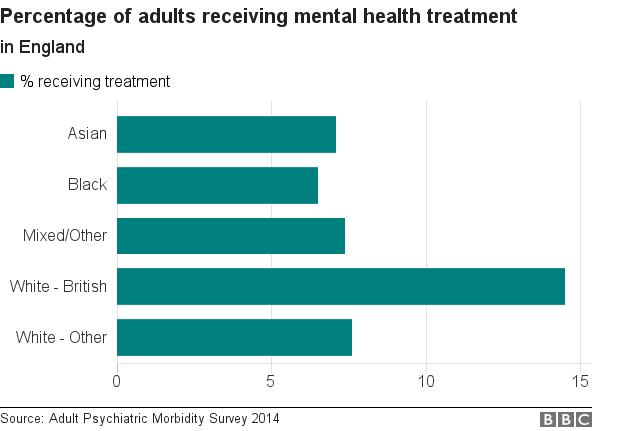

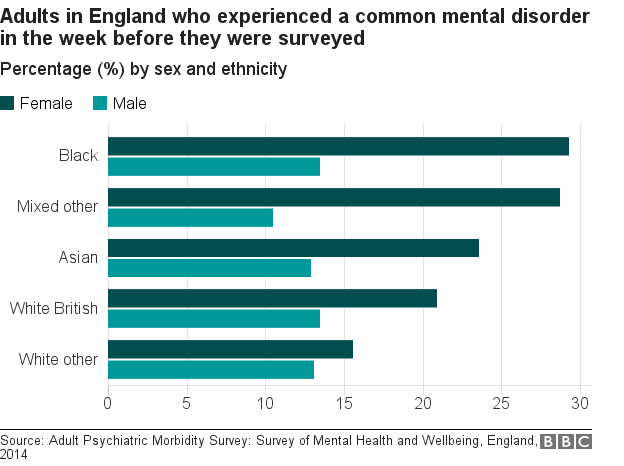

Figures show white British people are accessing more help while BME women are most likely to have a mental condition.

Campaigner Asha Iqbal said fears of shaming the family and not being the "perfect wife" made her anxiety worse.

Latest NHS figures, external show a white person with mental health issues is twice as likely to be receiving treatment than someone from an Asian or black background.

The statistics also show women from such backgrounds were most likely to experience a mental health disorder.

The issues prompted Ms Iqbal, 30, to set up an organisation Generation Reform, external to help other people with mental health issues.

Miss Iqbal, who started suffering anxiety aged 10, said growing up as an Asian woman brought cultural expectations.

"You've got to present yourself in a certain way so that you're marriage material for certain people," she said.

"You don't really want to open up in case you suddenly ruin your whole reputation as to how you present yourself - no-one wants an unstable wife."

She said "attitudes of people around them" had been barriers to recovery for those she spoke to.

"They don't believe they have an illness, it's easier to explain things they don't understand by saying it's black magic," she added.

Asha Iqbal started suffering with anxiety when she was aged ten

Heather Nelson, chief executive of the Black Health Initiative, said cultural beliefs compounded stigma and that services needed to be more aware of that.

"There's some belief that people from some ethnic backgrounds have a stronger resistance to drugs, therefore may feel they're more likely to be prescribed higher doses of medication," she said.

"Some services aren't equipped for certain communities and the taboos they face. You need to understand where people come from to understand what they're facing."

Sana Nosheen, a 21-year-old blogger from Bradford, said she developed post-natal depression after the birth of her son a year ago.

She said she was lucky her family and husband had supported her through it as it would have been "one hundred million times harder".

'Difficult to talk'

Marjorie Wallace, chief executive of SANE, said the charity received fewer calls from Asian women compared to those from other communities.

"Our experience is that women and young girls from South Asian communities often carry a great sense of shame and the need to preserve their family's honour," she said.

"The difficulty is that people, especially young girls, can find it difficult to talk to their parents and family about their mental health problems."

The Department of Health said it was planning to reform the Mental Health Act and an independent review was under way.