Covid-19: Losing both parents to coronavirus

- Published

BBC reporter Cathy Killick shares her experience after both of her parents died with Covid

BBC reporter Cathy Killick lost both of her parents to Covid-19 within six weeks. Her father died on 2 December and her mother on 12 January. Here is her story.

I've been a reporter for the BBC for more than 30 years. In that time I've interviewed dozens of people who have experienced loss. I've done my best to convey their emotion faithfully, not having experienced it myself.

Now I find I am one of those people.

I've always been struck by the bravery of those I've talked to and I've always been grateful to them too. Journalism can only exist if people are willing to share their stories, so I'm going to share mine not because I'm brave, but because I owe them.

My parents' deaths came at the end of a horrible year.

They lived in a care home 10 minutes' walk from where I live in Leeds. Before Covid, I would visit them pretty much every day.

My dad, Ted, had dementia and lived on the top floor. My mum, Elizabeth, had Parkinson's and lived on the ground floor with fewer staff because she was pretty independent. She could pop up to see my dad whenever she liked.

They were happy in their care home. It was a cheerful, bustling place with a coffee bar and plenty of places to socialise. The staff were lovely too, and made an effort to get to know my parents. Whenever I visited, I saw kindness.

Cathy's parents lived in a care home a short walk from her own home in Leeds

When Covid arrived, the socialising had to stop. I saw my dad just a handful of times between March and December. I'm haunted by the thought that he felt abandoned by me and my mum. He didn't really understand anything about the virus as his dementia was quite severe.

My mum, however, had the great good luck to have a room at the front of the building where I could stand on the pavement and talk to her on the phone while looking at her through her window. She called it "swinging by" and her face would light up when I appeared.

She was confined to her room for much of the time as her carers did everything they could to minimise the chance of infection. They did really well to keep the home Covid-free for as long as they did.

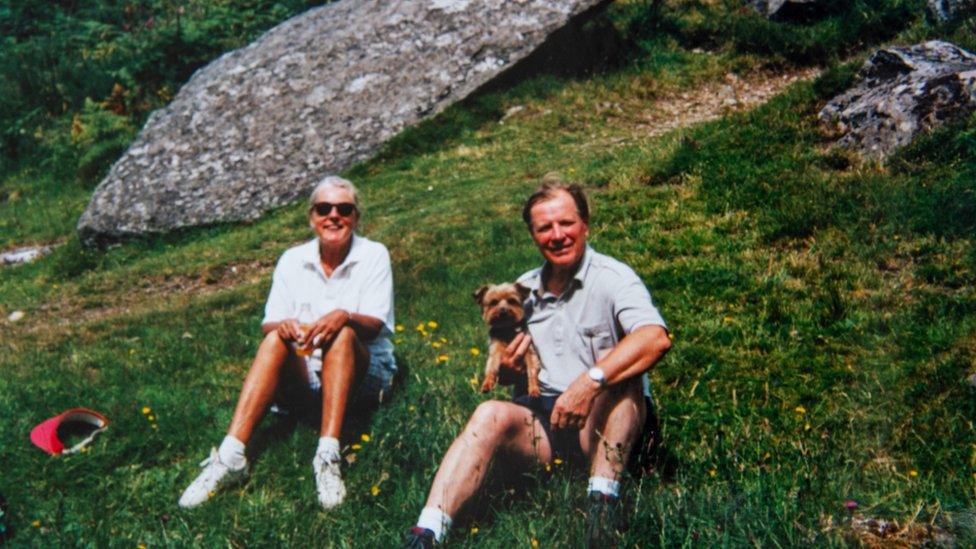

The couple shared a love of camping and the outdoors

In late November, I got the call I had been dreading. My dad had tested positive.

Removing someone with dementia from their familiar surroundings can cause great distress. His GP also felt that he would not tolerate the breathing treatments on offer. Together, my brothers, sister and I decided Dad should stay at the home and receive care from the district nursing team. We were allowed to visit him individually and for short periods wearing PPE. He was very sleepy and unable to acknowledge our presence.

I held his hand and told him what a great dad he'd been, not knowing if I'd ever see him again. He died 12 days after his positive test at the age of 87.

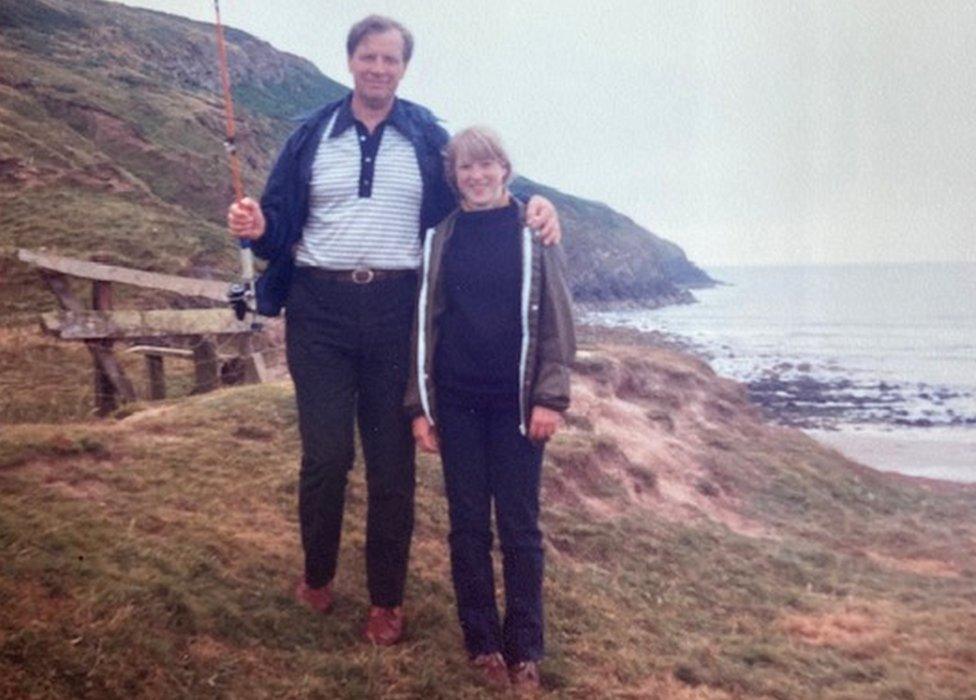

Cathy has fond memories of fishing trips with her father

My dad had had a really full life. He came from a long line of Lincolnshire farmers but stayed in the Army after doing National Service. He joined the Royal Artillery and had glamorous postings to Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Germany. He bought a caravan and took us camping on wild sites with no facilities apart from a tap. He cooked up adventures for us - mackerel fishing in a tiny rowing boat. The Army gives you friends for life and many of them wrote me such lovely letters of condolence. They talked about his kindness and lively interest in other people.

He would never describe himself as such but Dad was a feminist. He encouraged me and my sister in our careers, and taught us to face the world with courage and friendliness.

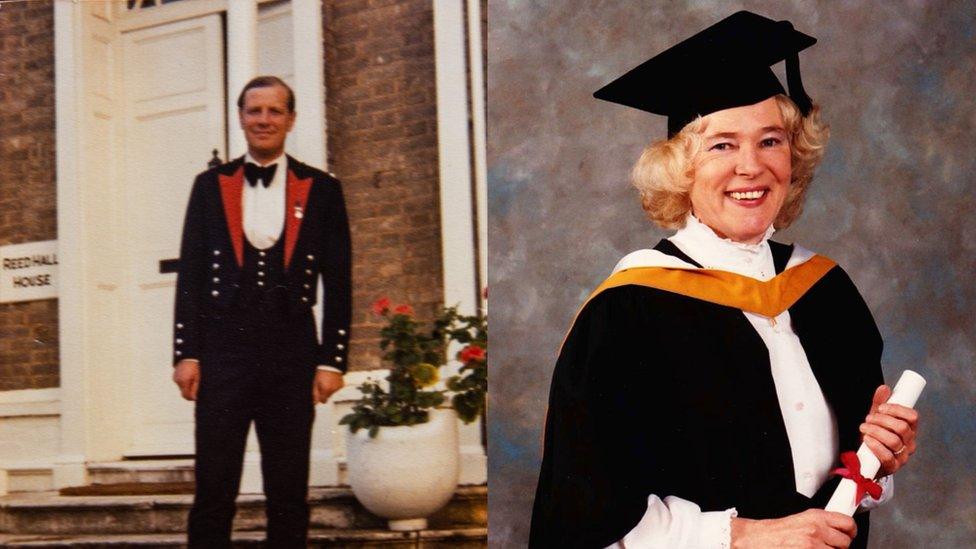

The couple met and married in the 1950s

He met my mother in 1955. She was a year younger and the daughter of one of his senior officers, so well used to Army life. She shared his sense of adventure. She loved bodyboarding and camping too. They had four children. But, by the 1970s, she wanted more from life than being a wife and mother. It had always rankled with her that her parents had not felt it worthwhile for girls to go to university.

So, at the age of 37, she went to college to get a teaching degree. She used her dressing table as a desk and studied at several different colleges as Army postings moved us all round the country. She became a primary school teacher and really loved her work, gaining a master's degree in children's literature.

Ted pursued a career in the Army and Elizabeth returned to education in her 30s gaining a teaching degree

Reading was one of the things that kept Mum going during the long months of lockdown but I could see she was losing heart. From the outside, she took Dad's death very calmly. But two days before his funeral, she had a stroke. The hospital was not allowing visitors, but they made an exception for me on compassionate grounds. My mum had lost her husband of 63 years, yet no-one had been able to give her a kiss or a hug in consolation. I was allowed to see her once to tell her about Dad's funeral.

It was painful that so few people could attend his send-off but the Royal Artillery Association sent a standard-bearer and a trumpeter to play the Last Post and represent all of his Army colleagues. It made a big difference to our sense of doing right by our father. I took some photos to show my mum in hospital. I think that visit was one of the toughest experiences of my life. My mother was so frail and so sad and I felt broken myself.

A Royal Artillery Association standard-bearer attended Ted's funeral

Mum left hospital just before Christmas and went back to the care home to recover. She was doing well, able to walk about with her frame and we had some good chats through the window on the phone. The vaccine was starting to be rolled out and we talked about trips out and going for a drive to Almscliffe Crag - a local beauty spot she liked.

Then, on one of my "swing-bys", Mum didn't smile when I tapped on her window. She looked dreadful and her speech was slurred. It seemed as though she was having another stroke, but after she'd arrived at hospital she tested positive for Covid. For six days, I couldn't see her. Then came the call that I could. On Covid wards, that usually only means one thing - that the patient is not expected to recover.

She could not go back to the care home because it was Covid-free, so Mum came home to me - to a hospital bed, set up in our sitting room.

Elizabeth Killick spent her last few days at Cathy's home

I am so grateful to the district nursing team, carers and night sitters who made that possible. They were outstanding and treated us all with such compassion and kindness. Those last days with Mum were intensely moving. We played her music and read her poems and tried to repay her for all the love she'd shown us over the years. Over the course of five days, her breathing slowly became more and more shallow.

My siblings sat with her on FaceTime and carers came four times a day to change her position and keep her clean and comfortable. I will never forget those carers. The respect and tenderness they gave a stranger was the most humbling thing I've ever seen. For me, it transcends the misery and privations of the pandemic. It gives me something precious to hold on to and has left me with a memory of something truly beautiful.

In the weeks since, I have been on the receiving end of so much kindness and thoughtfulness. Our lovely neighbours shopped for us while we were isolating after Mum's death. Friends have left cake and gin on the doorstep. Cards, flowers and letters have cheered me up with memories of my parents. These small acts have made a big difference. Never despise these little things, or think them insignificant. They are the best of us and they are what make our current times bearable.

Ted and Elizabeth Killick with their four children Jenny, Jeremy, Cathy (centre) and Tim