Batley Grammar School: Blasphemy debate leaves town 'at crossroads'

- Published

Protesters gathered outside Batley Grammar School's gates last week

Just weeks after secondary schools fully returned to the classroom after months of home learning, a religious studies lesson in a West Yorkshire town provoked protests outside the school gates and a free speech row stretching far beyond the county's borders.

Pupils at Batley Grammar School being shown an "offensive" cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad - reportedly taken from the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo - brought crowds of campaigners and claims a member of staff was in hiding, fearing for their life.

The rush of opinion that followed included interventions from government ministers and the Archbishop of Canterbury, while a petition backing the teacher apparently started by a pupil has gained more than 70,000 signatures.

A week on, the BBC spoke to people in Batley to find out how they felt about being at the centre of an international media storm.

Batley, a historic mill town surrounded by some of West Yorkshire's biggest cities and towns, spreads out from its library's clock tower and up both sides of the surrounding valley.

Located about nine miles south west of Leeds, with a population of about 80,000, it last became the focus of the national media when its MP Jo Cox was murdered in nearby Birstall in 2016.

The town last became the focus of the national media when its MP Jo Cox was murdered in 2016

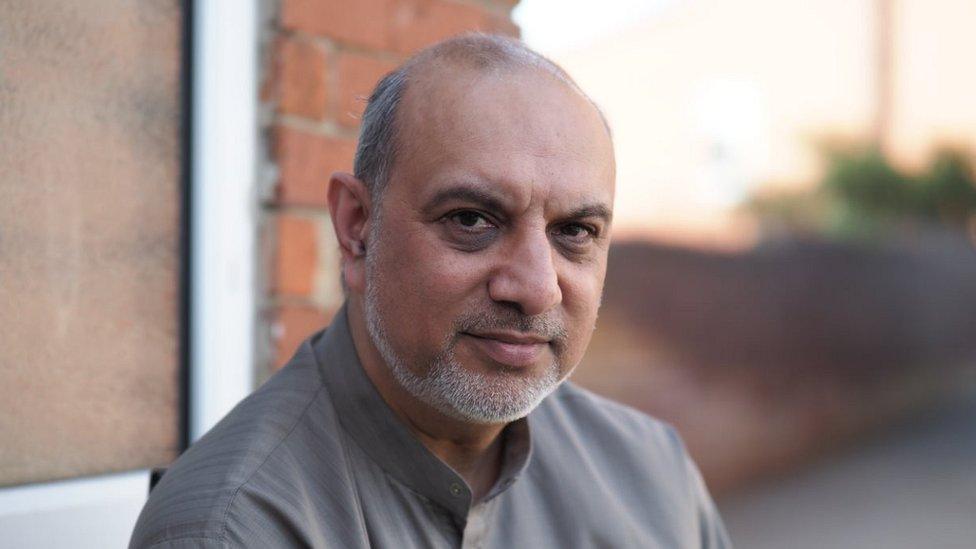

High up on the opposite side of the valley to the grammar school, Abdul Ravat sits with his youngest daughter underneath a blossoming cherry tree in the afternoon sun.

Mr Ravat says the situation had provoked debate within his family, with 16-year-old Halimah surprised to see her former teacher making headlines.

"The school's profile has changed since the last Ofsted report, the majority of the school is of a South Asian origin and of Muslim faith, so you've got to factor that into the equation," Mr Ravat says.

"Why wasn't there someone internally asking that question in terms of the lesson plans?

"Given the context of your population, you should consider how it would be received."

His daughter, who studied at the school until last year before moving on to attend sixth form, says: "Our teacher did have a different take on lessons, but he was still a good teacher.

"I don't think he intentionally meant for all of this to happen, he was the type who questioned a lot of things.

"But that was just used to spark discussion and it was effective as we all engaged in debates."

Abdul Ravat says some media outlets had tried "to stoke up divisions" with the story

Mr Ravat recalled meeting Mrs Cox, who visited Mount Cricket Club just two weeks before her death, and her message of people having "far more in common with each other than things that divide us".

"I feel towns like Batley are at a bit of a crossroads because I feel integration is weak in this area," he says.

"The work the Jo Cox Foundation does is great, but we're swimming in the pond and there's a big river of issues we need to confront.

"Brexit and even the pandemic have really polarised communities - we're all hurting but it seems to me that it's currently fair game to blame each other."

Why does depicting the Prophet Muhammad cause offence?

There is no specific, or explicit ban in the Quran, the holy book of Islam, on images of Allah or the Prophet Muhammad - be they carved, painted or drawn.

However, chapter 42, verse 11 of the Quran does say: "[Allah is] the originator of the heavens and the earth... [there is] nothing like a likeness of Him."

This is taken by Muslims to mean that Allah cannot be captured in an image by human hand, such is his beauty and grandeur. To attempt such a thing is seen as an insult to Allah.

The same is believed to apply to Muhammad.

Chapter 21, verses 52-54 of the Quran reads: "[Abraham] said to his father and his people: 'What are these images to whose worship you cleave?' They said: 'We found our fathers worshipping them.' He said: 'Certainly you have been, you and your fathers, in manifest error.'"

From this arises the Muslim belief that images can give rise to idolatry - that is to say an image, rather than the divine being it symbolises, can become the object of worship and veneration.

Read more: The issue of depicting the Prophet Muhammad

Not far away from the Al Hikmah community centre, where Prime Minister Boris Johnson recently praised volunteers for their work to tackle Covid vaccine myths, employment lawyer Yunus Lunat is reflecting on a manic few days of phone calls and WhatsApp messages.

Mr Lunat, who represents the newly formed Batley Parents And Community Partnership, said: "There's a lot of focus on the negativity and the protesting but the unanimous messages that were flying around were not to protest and a large number of them were not even from Batley.

"We've had policing bill protests in Bristol, anti-lockdown protests in Bradford and the disruption here is not even comparable, I don't think they should have been in the news," he said.

When asked how blasphemy should be discussed in the classroom, Mr Lunat replies: "If you're teaching a class about racism, would you start by using the 'n' word? If you're teaching children about the potential effects of pornography, would you show a pornographic film?

"You can still have a healthy discussion or debate without it - the problem comes when this image of a holy man is reinforcing negative stereotypes."

Batley is in the metropolitan borough of Kirklees and is roughly nine miles south west of Leeds

Down the valley, not far from Bradford Road's garages and the steep bank up to the grammar school, families and friends are enjoying the first hot afternoon of the year in Wilton Park.

On a shaded slope looking down on the boating lake and an ever-growing queue for the ice cream van, two friends are mulling over the recent events outside the nearby school.

"If you're going to teach them about religion then you have to look at every aspect," says Rachel, 49.

"I can understand people objecting to something which might have been said or shown but you have to remember they weren't there at the time, you need the context of the lesson as a whole and what happened."

Nick, who has travelled from nearby Leeds to meet Rachel for a picnic, says: "We don't have blasphemy laws, there aren't any laws broken here.

"To base somebody's entire working profession on five to ten minutes of one lesson and say they therefore should no longer teach is preposterous, it's silly.

"If you've got enough time to be standing outside an open school, go do something useful, go and help someone in the community rather than lambast and intimidate somebody."

Wilton Park sits at the bottom of the valley a short distance away from Batley Grammar School

Enjoying a coffee on a bench near the park's tennis courts and bowling green, "Batley born and bred" Mohammed Patel says he can see both sides of the argument.

Mr Patel, who works as a human rights lawyer, says: "On the one hand here you've got the right of Muslim parents or community who are clearly offended by the cartoon in question, on the other end you've got the equally competing view that in a progressive, diverse and multi-cultural society these issues are appropriate for examination.

"I say this carefully, but perhaps one very small benefit of the protests is that perhaps it has opened up a discussion, there is a conversation to be had."

Mohammed Patel says many different groups will need to "find a way to solve this particularly sensitive and complex issue"

Kim Leadbeater, Jo Cox's sister and an ambassador of the foundation established in the former MP's memory, says: "We believe that talking together and respecting difference is the best way forward. It is our hope that nobody wants division and polarisation.

"In my view the main objective now should be to let the independent investigation take place in order to establish the facts around the situation, to listen to those who were involved and find a peaceful resolution."

Kim Leadbeater says she hoped all can 'find a way to come together as we unite to emerge from lockdown restrictions'

Batley Multi Academy Trust said an independent investigation reviewing how "the materials [which caused offence] were used" will begin on 12 April, with an outcome expected in late May.

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published31 March 2021

- Published27 March 2021

- Published27 March 2021

- Published4 October 2021

- Published25 March 2021